Kermit thought he had it bad?

Poor Elphaba, born as green as a parrot to the governor of Munchkinland and his unfaithful wife, was scorned and hated, an alien being who could not help but become a grumpy outcast. But she had a big heart and a good mind and a way of interpreting the Grimmerie that made her powerful, and thus potentially useful to those like the Wizard of Oz and his press secretary Madame Morrible, who are attempting to impose immoral control—including making sure animals can't talk—over a complacent but fearful citizenry.

No, this isn't the subject of some weird dream I need to take to my shrink, or a codeine-cough-syrup-induced hallucination. It's part of the plot of one of the most unusual phenomenons of recent American Broadway musical theater history, the overwrought and overstuffed, wildly but wonderfully imagined Wicked. And it's bursting the seams of the TCC Music Hall for a couple of weeks courtesy of Broadway in Tucson.

The musical is based, very loosely, on Gregory Maguire's 1995 novel, Wicked: the Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West. It's an imaginative—and hugely elaborate—backstory of what most of us know only through L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Baum's story of Dorothy and Toto as they try to negotiate what amounts to a dream resulting from a knock on the noggin became MGM's The Wizard of Oz, which in the 1960s entered our national collective consciousness as an annual television event urging us to locate and embrace our hearts, brains, and courage, and introduced us to the existence of good witches and bad witches.

Maguire decided to explore what exactly made the Wicked Witch of the West wicked and created a complex geopolitical-sociological fantasy world in which Dorothy and friends were barely players. Universal's Marc Platt thought it would make a great movie, and got Maguire to sell him the rights. But musical theater composer Stephen Schwartz—who is responsible for Godspell and Pippin, among others—thought it would work best onstage, and persuaded Maguire to transfer the rights to him. Winnie Holtzman, who helped fashion the critically acclaimed TV series My So-Called Life, starring a very young Claire Danes, was wowed by Maguire's story and identified what would constitute the heart of a theatrical production that would of necessity be a stripped-down version of Maguire's tale.

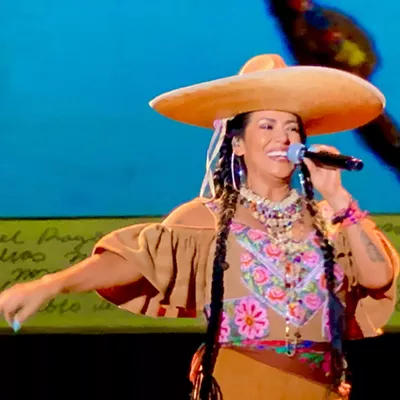

So she and Schwartz and director Joe Mantello shaped the main storyline to be about the love and friendship between two young women who seem to be so wildly different that such an alliance would be highly unlikely, if not impossible. Elphaba (Dee Roscioli)—sturdy, socially awkward, and strong enough to ride out what the cyclonic force field of fate pulls her into—finds in schoolmate Galinda (Jenn Gambatese), who becomes Glinda, the Good Witch, a shallow, sparkly, bubbly, very blond and pink opposite, one who is "tragically beautiful" to Elphaba's "beautifully tragic."

It's this contrast that justifies the noise and spectacle of Mantello's production and makes it all pretty appealing.

And spectacle there is. From the dragon flying, in a stationary sort of way, right at the heads of the audience to the gigantic grinding gears of a clock that anchors the story visually to the dozens of seamlessly shifting settings, Eugene Lee's set design is a marvel, as is Kenneth Posner's lighting. Then there are Tom Watson's wigs and hair and Susan Hilferty's costumes (more than 200 of them) so fanciful, so odd, so clever, so downright delightful.

The road show doesn't slight the fullness of the visual and auditory experience of the Broadway original. And one really can't help but be impressed, not only by the invention of the design elements, but also by the skill and effort it takes to bring them to us smoothly and safely show after show.

The cast here is also first-rate, including the hard-working troupe of supporting singer/dancers. Kim Zimmer as Madame Morrible is a treat. And quite fine is Timothy Britten Parker as Professor Dillamond, a respected teacher who also happens to be a goat, threatened by the ever more fascistic bent of the political landscape. Tom McGowan, a familiar face from TV and film, gives the Wizard a satisfactory spin, and Justin Brill as Boq, the Munchkin hopelessly in love with Glinda, makes us care about how folks take advantage of him. Curt Hansen is Fiyero, the love interest of both witches. Although physically striking, has a hard time finding both the surface and depth of this rather tricky character.

But the critical characters are Glinda and Elphaba, and if they don't click, there's nothing much left but a stage full of stuff. However, Roscioli and Gambatese do, and there is a touching sweetness that grows both in spite of and because of their differences. Like the Scarecrow, the Tin Man and the Cowardly Lion of Dorothy's dream, they find themselves in the right place to discover and embrace their unique selves, and perhaps most important, the courage to act.

The most familiar songs, like Defying Gravity, Popular and For Good worked well, but Elphaba's No Good Deed in Act 2 was overpowered by the orchestra. And that's too bad, because the song is such a critical turning point for Elphaba and thus the story.

Wicked's story is really more complicated than it needs to be, and has more undeveloped thematic threads than the tax code has indecipherable rules. Still, those girls have their winning ways, and if you keep your focus on them as they tumble through the outrageous, kaleidoscopic sensory overload in which they exist, I'm pretty sure you can enjoy some thoroughly wicked entertainment.