I-10 heading west travelspretty much a straight line from the Atlantic Ocean to a point just south of downtown Tucson, where it takes a hard right north towards Phoenix and despair. To the left lies Mexico, lurking like a huge Gila monster. One can feel its hot breath all the way from El Paso. It's a junction that acts as a vortex, an asphalt and concrete divining rod with the aquifer underneath shrinking by the day. Two imposing granite and pine partitions—the Catalina and Rincon mountains—form a natural shelter for the city, keeping past lives and disappointments at bay. An outpost for the lost and weary, a sanctuary for misfits, miscreants, and misers, Tucson is the town that refuses to be a city, even with a half million denizens that now call it home.

A friend of mine from San Francisco once asked me why Tucson has so many drifters and dreamers—this was right after a bartender jumped over our beers and knocked out a surly drunk in a dive called The Boondocks—and I replied that people trying to get to LA run out of gas or the radiator goes and they just wind up staying. They find a weekly rate hotel, get a minimum wage job, and put off the better life in California for the next month or so. Soon, however, their physiology starts to change, it's hot and dry and they become desert creatures, moving slowly from shade to shade and never without shades, which could leave one blind. They morph into cactusheads and like a saguaro that only grows an arm a century become patient in spite of themselves. Without really trying, they soon develop a philosophy they can live with. It really is quite extraordinary.

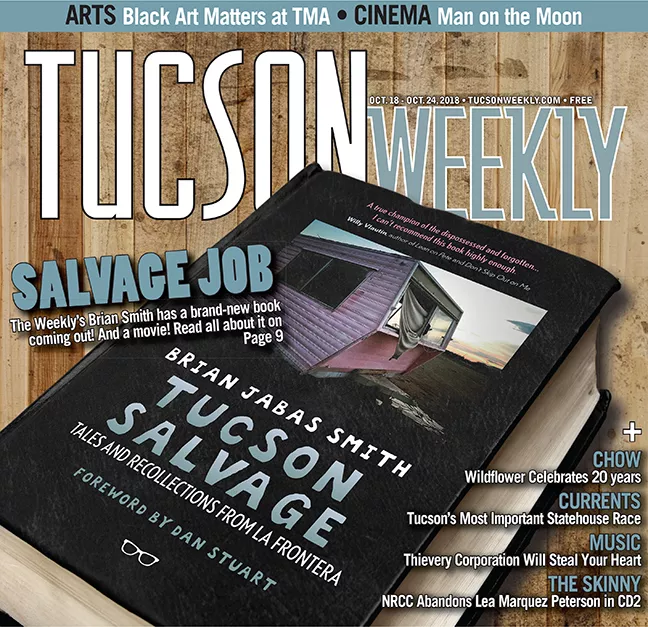

Brian Jabas Smith knows these desert dwellers, his people, just like Studs Terkel knew his in Chicago. Born and raised in Tucson, a champion cyclist and fantastic punk frontman in his youth, he came and went a few times but finally returned for good when life and love became unbearable in a rust belt capital where the sun doesn't shine but a few months a year, and half as bright at that. To pay rent and keep the swamp cooler blowing, he put his hard-earned journalist chops to use and started writing a column for the local weekly. He called it Tucson Salvage and dedicated it to the kooks and crannies of a city that only a native can uncover and fully understand. It really was no different than his childhood hikes in the desert, turning over rocks and poking into holes to discover what others wanted no part of: strange and sometimes venomous critters to be treated with respect and wonder.

A naturalist back in his element, he hit his stride in middle age, the opposite of poor brilliant Joseph Mitchell hiding in his New Yorker office with nothing left to type. A collection of critically acclaimed stories soon arrived called Spent Saints, bittersweet tales about the demon meth and the endless 40's of nasty brew that used to sustain him night after night, before sanity returned like a favorite cat not seen in years. Mirroring his characters and subjects, Smith allowed himself to believe in the desert's power to bake the hurtful past right out of you, leaving only the sanctity of today, this moment right now. He replaced the racing bike of his youth with long rambles through town to see what's new, or more often, what has changed and will never return.

It was the perfect match all around, writer and environment, and unlike crusty Edward Abbey, who aged about as well as mayonnaise left in the sun, Smith held onto his humanity like a shield and used empathy like a weapon, disarming all with his earnest queries and impish grin.

The portraits in Tucson Salvage are wide and varied, from legless gangbanging artists to Mormon baseball mascots to crime scene clean-up cowboys. Swap meets and tourist traps figure prominently, as do junkyards, dive bars and greasy spoons. Smith has the time and patience to duck into the places we all rush by and wonder about; or to stop and chat with a street "crazy" who is anything but. He never patronizes anyone, or worse, romanticizes life's hard knocks and cruel turns. Foot in door, his genuine curiosity and natural charm encourages his subjects to open up and share sweet joys and triumphs they haven't thought about in years, or reveal poignancies that are too hard to unload on families or friends, only a kind stranger will do. Smith observes, listens, then transcribes... a post-punk priest or traveling sin-eater, he captures the stories folks didn't even know they had, and stitches them back into the communal quilt that makes us all stronger, safer, more human. It's holy work, no doubt about it, but done by a fallen altar boy who truly knows what it's like to feel completely alone and abandoned, all bridges burned, no direction home. Smith is happy to listen because it quiets his own internal voices that taunt and harangue, carnies looking for an easy mark. We can all learn from this, the basic grace of an open heart and mind that can deliver us from our own worst impulses, from el mal that waits like a coyote eyeing a toddler, grinning from ear to ear.

Lately I've grown weary of life in a megalopolis, and as I read over Smith's columns a second and third time, I find myself dreaming about returning to the desert, to become a character worthy of his attention. I imagine working as a tight-lipped night clerk in a neon drenched motel on Miracle Mile, or maybe a happy-go-lucky pool cleaner sporting a huge Asian rice hat with arms as dark as coffee. I could quit drinking, lose 20 pounds, buy a potter's wheel, keep a pet snake, fall in love, read the Bhagavad Gita, stop trying so hard. Austin aside, Tucson is the original slacker town, and regardless of how many transplants from stress-bomb states arrive, that will never change. The desert welcomes pilgrims, but also shuns past conceits. Start over or leave, just too damn hot to carry around all that baggage, grab yourself a frozen Eegee's instead.

It's worth noting that many of Smith's interactions are with people who hold opposite views to his own: guns, the current president, immigration, etc. Smith doesn't argue; instead, he'll bring up a point or ask a question that subtly prods his subject into acknowledging their own uncertainty, their own closely held deceits. He would make an exceptional diplomat, or cultural anthropologist, or the perfect bartender. His eyes see what we don't, what we've become inured to, the terrible truth of ordinary people trying to live with dignity and honor in a world that has gotten harsher and more polarized by the day. These pieces will stick around long after Smith and his menagerie have passed, and will stay with me until my own reckoning as well. Read and enjoy, but keep a tissue at hand, you're gonna need it.

Reprinted with permission from the foreword of Tucson Salvage: Tales and Recollections from La Frontera. Copyright @ 2018 Brian Jabas Smith. All rights reserved.