Once into the Night

By Aurelie Sheehan

Sheehan is Arizona's most convincingly inventive writer of fiction and she breaks new ground—again—in this slim volume of 57 stories. If that last part sounds like a contradiction, consider the case of a sex worker who greets her guests with the line "these sliced pickles might be excellent on your sandwich," or a painter who describes boredom as "a cockroach in a Snickers wrapper." One of the many pleasure of reading Sheehan is never being able to guess where she's taking you or where a particular thought is going to lead. These stories—some as short as a paragraph and most of them dark—are like peeks through windowshades in an accursed village. —Zoellner

The Color of Rock

By Sandra Cavallo Miller

Dr. Abby Wilmore works at a clinic next to the Grand Canyon, trying to leave her addictive past behind, and in the move discovers new relationships with people and the dazzling gash in the earth near her door. A novel rich in insights and nature writing, and, unsurprisingly, the canyon plays a starring role with its "stark display of eons, as if the planet had suddenly bared its soul and let strangers see its past." —Zoellner

La Llorona: Ghost Stories of the Southwest

By Christopher Rodarte

In Mexican folk legend, La Llorona is the poor wife of a nobleman who drowns her children in revenge for her husband's inattention, then regrets it, and spends the rest of her days as a wailing ghost searching for her lost sons. As a New World version of the Greek story of Medea, it has been used for hundreds of years as a tale used to frighten children with the memorable cry ¿Donde estan mis hijos? Christopher Rodarte, a teacher at Sam Hughes Elementary School, gives an expert retelling—and critical examination—of the multiple stories about the "ditch witch," many of them with a particularly Tucson spin. —Zoellner

Saints, Statues, and Stories: A Folklorist Looks at the Religious Art of Sonora

By James Griffith

"Big Jim" Griffith has more than earned his status as a beloved local storyteller and anthropologist, and he shares more than 60 years worth of observations about the sacred icons of northern Mexico and the legends that surround them. Most towns, for example, can boast of a local narrative that "when a group of hostile nonbelievers attacks the village, the patron saint of the church (and therefore of the village) foils them, usually through some sort of an illusion." A delightful combination of academic rigor and easygoing fireside dialogue. —Zoellner

Secret Tucson: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful, and Obscure

By Clark Norton

One of the many pleasures of living in Tucson is that the town keeps revealing hidden corners and mysteries, even to lifelong residents who thought they knew it all. Nobody can ever know the true depth of the Old Pueblo, but Clark Norton gives it a try in this compendium of local quirks. If you want to know how to sit in John Wayne's favorite seat at the Fox Theatre, where the Hohokam ball courts are located at the base of the Catalinas, or the odd story behind the Paul Bunyan statue at North Stone and Glenn, this is the book for you. —Zoellner

America's Most Alarming Writer

Edited by Bill Broyles and Bruce Dignes

Taking its title from a remark from poet Jim Harrison meant as a high compliment, this is a collection of 50 essays about Tucson's restless mountain lion of letters, the brilliant and baffling Charles Bowden, who turned out incandescent books in two-month bursts of morning writing jags, even as he held drunken court in the afternoons with a revolving cast of eccentrics in his house off Ninth Street. Bowden comes to life in these pages as a man of skyrocketing talents, punishing work habits and manifest human flaws. His legacy has only continued to grow, thanks to a reissue of some of his most important work by UA Press, and this supplement to his body of work is an indispensible guide to the passions that motivated him. (Disclosure: one of the essays within is mine). —Zoellner

The Chasers

By Renato Rosaldo

When he attended Tucson High School between 1956 and 1959, Renato Rosaldo was at the center of a club of 12 mainly Mexican-American friends who called themselves "The Chasers," and they found their own way through the old rituals of chasing girls, work and dreams while pushing thoughts of self-construction necessarily to the side. This is a powerful evocation of memory, oppression and an attempt to redeem time. He writes in minimal language that betrays strong emotion: "In my family's '51 Dodge, I drove across town, east to west, house to house, picked up the guys, hard-assing the entire trip. I remained mum, under a bushel basket, no sign of me." —Zoellner

The Death and Life of Aida Hernandez

By Aaron Bobrow-Strain

Bobrow-Strain spent hundreds of hours with the teenage mother of the title—which is, regrettably, a pseudonym—in order to tell a detailed story of the outrageous criminalization of border-crossing, which had been a casual and unremarkable way of life for the citizens of Douglas, Arizona and Agua Prieta, Sonora up until America's recent bout with toxic racial politics. Aida is sympathetic, but she is no saintly martyr, either—her impulsive choices are not always good ones. In short, she is one ordinary human being caught up in the long-playing folly of the militarized border. The book is especially astute on the intertwined sociology of the twin towns, as well as the dusty Douglas suburb of Pirtleville where Aida grew up. —Zoellner

The Light Years: A Memoir

By Chris Rush

The Tucson painter Chris Rush had an unbelievably chaotic childhood as a middle child in an affluent Catholic family in Trenton, N.J. in the midst of the Age of Aquarius. He chronicles his attempts to find enlightenment through dealing LSD, wearing a pink cape, flopping in communes, making hitchhiking jaunts across the Southwest, chasing UFO cults and living as a hermit in the Rincon Mountains. Rush writes in a deadpan style as if all of this were normal, making the sacred mess all the more intriguing. Best understood as a bildungsroman of a visual artist, Rush writes eloquently of chasing the biggest high of all—creativity—along with his "unwholesome desire for all things vine-choked and Victorian." —Zoellner

Empire of Borders: The Expansion of the US Border Around the World

By Todd Miller

This is a head-spinning look at the reach of the U.S. "border security" apparatus that extends more than a thousand miles from the mainland, and a terrifying glimpse into the future of "smart walls" that take surveillance and personal identification to new levels and make it even likelier that humanity will further segregate itself along lines of income and ethnicity as climate change starts to menace fragile coastal regions.

Miller—who lives in Tucson—backs up his suppositions with hard field reporting, making his conclusions more difficult to refute or dismiss. —Zoellner

The Lightest Object in the Universe

By Kimi Eisele

Here's a relentlessly optimistic novel about the apocalypse. Eisele is a dancer and photographer living in Tucson who is used to working across genres, and she tells what amounts to a road-trip love story in a country stripped of its electricity and government. Carson is walking a set of railroad tracks toward the West Coast in hopes of finding his girlfriend, who has been busy creating a new kind of cooperative village that never could have existed before the collapse of nation-states. Eisele isn't always convincing in her descriptions of an unattractive future, but her faith in the benevolent willpower of the people ranks with that of John Steinbeck. —Zoellner

The Unfortunate Demise

of Marlowe Billings

By Dan Stuart

Yes, on-off Tucson resident Dan Stuart began this novel when he was insane, adrift in Mexico, a marriage and a dreamy career of rock 'n' roll stardom behind him. So many of the dead greats of all colors and genders have taught us it is when the chips are down we get the best writing, and so we get this, a twisting semi-odyssey of improvised adventures or, maybe, a 50,000-word suicide dispatch. This slim tome (like the best Jim Thompson) follows Stuart's false memoir debut, The Deliverance of Marlowe Billings.

This novel centers on Marlowe Billings, at first a purely unlikable protagonist—or a purely self-reflexive Stuart persona—in an adulterous yarn involving cartels and antipsychotic drugs. It is a high-stakes, often humorous soul-search amidst liminal spaces—American versus Mexican culture, old-family stability versus the often selfish desires of self-immolation and rich exploration. The prose bites in joyous indulgence and swift passages, stirs anger and mercy along the way, until the imagery chimes sweetly, post-rain moments where marigolds grow from coffee cans and a laughter of trumpets signals inevitability. We ride shotgun in his longing to be stiffening under sheets next to Mexican murder victims in front of a church, just how he'd fantasized in his former life of "being buried under the boardwalk on Staten Island when the insomnia hit." The longing for his son, and tender comraderies. But wait, there are the upticks into literary-thriller land, and into quiet moments of sadness and reflection. Marlowe the antihero. —Smith

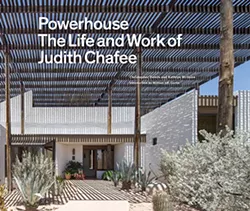

Powerhouse: The Life and Work of Judith Chafee

By Kathryn McGuire and

Christopher Domin

Finally. Twenty-one years after her death in 1998, and 50 years after she returned from the East to make her mark on Tucson, architect Judith Chafee has the book she deserves. Powerhouse: The Life and Work of Judith Chafee testifies to Chafee's brilliance at creating buildings that "live in harmony with the desert." She learned from the indigenous and Mexican architecture of the past while making sleek modern designs. Her houses large and small are wonderful but as a female architect in a sexist time she won few public commissions, to Tucson's great loss.

The book is co-authored by two architects: Kathryn McGuire, who was closely associated with Chafee for some 20 years, as her student at the UA, as an architect in Chafee's practice and as a friend; and Christopher Domin, an architect, author and UA professor.

These two have written highly readable essays on some 11 Chafee houses. Domin takes on early projects, including her live-in studio in a renovated adobe, and the much lamented Blackwell house in the Tucson Mountains. Foolishly leveled by Pima County, the loss of the house, Domin notes, still haunts Tucsonans.

McGuire's chapters cover the later period. Among other projects, she looks at Chafee's ingenious solution for a house in Sonoita, where local restrictions required the roof to be invisible to neighbors. And McGuire considers her design for the famed Rieveschl House, perched on a steep slope in the Catalina Foothills. The guiding principle for the project, Chafee declared, was "disturbing the grounds as little as possible."

An excellent biography incorporated into the text chronicles the influences that shaped her work, but also compassionately describes her personal sorrows.

The book is handsomely illustrated with full-color photos by Bill Timmerman and Ezra Stolle, along with Chafee's own drawings, hand-written notes and college paintings. A priceless photo of a toddler Judith catches her in an unfinished adobe room in her childhood home in midtown Tucson. Dressed in overalls and armed with a big shovel, the little girl smiles as she digs in the dirt, making her own adobes. It might well be Chafee's first building project. —Regan

A Stranger at My Door: Finding My Humanity on the U.S./Mexico Border

By Peg Bowden

It was just days before Christmas in the bitter December of 2013 and a cold rain was falling when a half-dead young Guatemalan man collapsed outside Peg Bowden's remote ranch house in southern Arizona. A longtime activist along the border, Bowden found her principles challenged: She knew that she could serve prison time for "harboring" if she brought the undocumented man inside, but she also knew that he might die if she sent him back into the freezing desert. Despite the frantic internal argument in her head, Bowden did the compassionate thing: She welcomed him into her house. She fed him, clothed him and gave him a warm bed, and allowed him to stay until he was well enough to travel and had a plan to get to his family in Nashville.

"Those days of law-breaking," Bowden writes, "were some of the most memorable of my life."

Those days also gave her a now-cherished friendship and a deeper understanding of the plight of migrants and asylum seekers. Her second book, A Stranger at My Door: Finding My Humanity of the U.S./Mexico Border, grew out of this encounter.

In telling the story of one man and his struggles over a period of years, Bowden helps us understand every migrant, and the tragedies that propel them. We learn about the corruption and poverty that leads Central Americans to flee, about the dangers of their desert journeys, and about the horrors of detention and deportation. Also the author of A Land of Hard Edges, a book about Bowden's work at the Kino Border Initiative migrant aid center in Nogales, Sonora, she inspires by doing the right thing, consequences be damned. —Regan

Along the Migrant Trail: A Borderlands Portrait

Photographs by Michael Hyatt

Foreword by Rebecca A. Fowler, Ph.D.

Michael Hyatt has long been a member of the Samaritans aid group, traipsing out into the desert bearing water and food for migrants. But Hyatt also lugs his camera into the wilderness to document the disasters that befall migrants hoping to find safety and respite in the U.S.

His new large-format book, Along the Migrant Trail: A Borderlands Portrait, has dozens of photos, in color and in black-and-white. The images are beautifully shot but they record the many horrors he has seen. In one photo, a skeleton—still wearing trousers—lies on a stretch of dry, rocky dirt in a desert outback, victim of a painful, lonely death. This photo, tellingly named "One of Thousands – Arizona Migrant Trail," was shot in 2008. But it could easily have been made in 2019, when known migrant deaths in Arizona alone hit 137, a jump up from fiscal 2018's 125 known deaths.

Hyatt is still at it, bearing witness, making images of migrants and the activists who try to help them. In Nogales, AZ, in 2018, he captured Arizonans protesting Trump's policy of wrenching infants and children away from their mothers and fathers. In Tucson in 2019, he photographed asylum seekers eating lunch dished out by Casa Alitas volunteers at the Benedictine Monastery.

And in the same year, he recorded Tucson artist Alvaro Enciso erecting a still another cross at the site in the far desert where still another migrant had died.

—Regan

In Another Time

By Jillian Cantor

Jillian Cantor, a Pennsylvanian transplanted to Tucson, is a prolific fiction writer drawn to stories set around World War II. Her newest novel, In Another Time, moves back and forth across decades, jumping from the early 1930s when Hitler was coming to power, to the postwar years when survivors were trying to rebuild their lives.

The young lovers at the center of this star-crossed romance begin their love affair in Berlin just as the Nazis begin to thrive. Hanna is an extraordinary violinist, Max a bookseller. But Hanna is Jewish and Max is not.

Cantor has carefully researched Hitler's rise; he creeps up step by step, and then, suddenly, all at once. And she portrays the ways ordinary Germans, Jews and non-Jews alike, were in denial about Hitler's abuses and the disasters to come. Readers can't help but notice a subtle link to the threats to democracy in the U.S. today.

The clever plot takes us back and forth from the future to the past, and hopscotches from Berlin to London, Paris and New York. In many ways, this is a mystery story. We know from the start that Hanna survived the war, but we—and she—don't know how she did. And Cantor even inserts a bit of science fiction, a rare twist in a historical novel, but somehow fitting in this semi-tragic love story. —Regan

Bar Flies: True Stories from the Early Years

Edited by Amy Silverman and Katie Bravo

For the last several years, some of best writers in the Phoenix area have been appearing at Bar Flies, a monthly storytelling event. Now 60 of the essays have been gathered into a handsome volume that USA TODAY books editor Barbara VanDenburgh calls "hilarious and heartbreaking in turn, resonating with the sort of honesty that makes you want to tell your own stories. Reading this book feels like sitting in a chic bar, nursing an old fashioned while the coolest person in the joint spins you a yarn." Full disclosure/humblebrag: I'm friends with many of the storytellers, but I'd recommend this even if I weren't.

—Nintzel

In the Shadows of the Freeway: Growing Up Brown & Queer

By Lydia R. Otero

Nine years ago, Lydia R. Otero's stunning book La Calle, Spatial Conflicts and Urban Renewal in a Southwest City demonstrated once and for all that Tucson's massive urban renewal projects of the late '60s were an exercise in racism. The book even inspired a giant outdoor play, performed by Borderlands Theater at the Tucson Convention Center complex, an urban renewal project made possible by the demolition of the homes of hundreds of Mexican-Americans and other minorities. Now Otero has a new book, In the Shadows of the Freeway: Growing Up Brown & Queer. Launched this month, it's a personal memoir that she says is the prequel to La Calle. —Regan

Anxious Attachments

By Beth Alvarado

Beth Alvarado's a book of essays has been long-listed for a Pen America Literary Award. After living for many years in the Arizona borderlands, Alvaro now lives in Oregon. In the book, published by Autumn House Press, Alvarado touches on 40 years of marriage and parenting, moving from birth to death, from love to loss, and back. But "none of the essays is purely personal," Alvarado writes on her website. "I am always conscious of larger cultural, historical, and political contexts, and the impress they have on our lives." —Regan

No More Deaths:Humanitarian Aid Is Never a Crime

By Sue Lefebvre

Sue Lefebvre carefully traces the 15-year history of an organization passionate about saving the lives of migrants in the Arizona desert. Lefebvre, now retired, was herself one of many volunteers who have walked through deserts, into mountains, in heat and cold, to bring life-giving water and food to desperate border crossers. The activities of No More Deaths came to wider attention this year with the failed prosecution of volunteer with the group, Scott Warren, on charges of "harboring" two undocumented men. After a unanimous jury briskly acquitted him, Warren declared that "the government failed in its attempt to criminalize basic human kindness." —Regan