There's this guy standing in line at Circle K with a live snake around his neck. The last time I saw a guy wearing a snake around his neck I scoring meth off him at an L-shaped, weekly-rates motel in west Phoenix, where dogs barked and babies cried, where the only cheer was the year-round Christmas lights that dropped between a nail in the roof's fascia to a nail driven into a sad palm tree.

Another lifetime ago.

Now I occasionally run into gentlemen in Tucson (well, twice since summer) sporting fangs-bared snakes creeping up their necks. Both times walking 22nd Street near Walmart. Each guy glowered, drunk on menace, hustle and too much sun. But those snakes were only tats, and I'm no expert on tattoo iconography, but I'm pretty sure they figured the etchings biblical. Evil, sin ...

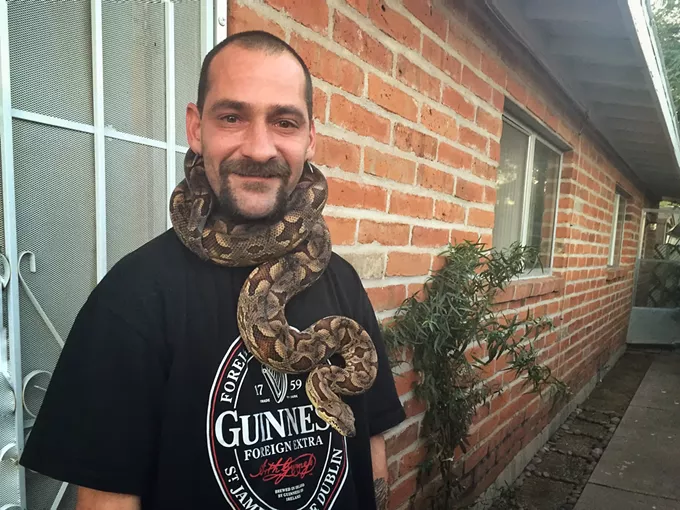

But they had nothing on this guy at Circle K, off Glenn on Tucson Boulevard. If you're really a badass, wrap a real, fence-post thick scaly reptile around your neck, one that stretches out to six feet. A snake whose head bobs in unpredictable, soundless ways, shows fangs. A snake who could strangle you. Like this guy’s.

And who strolls into a K with a snake wrapped on his throat?

This gangling gent with a Yosemite Sam mustache is no hustler, and he's not trying to scare anyone. Claims no faith-healer proficiencies. He's Sherman Ramsey, a dude struggling to get by like the rest of us. His developed young a fondness for reptiles, perhaps as a way to tolerate a brutal childhood. The snake, named Satan's Little Helper, works a visual metaphor too, you might say.

The snake's a non-venomous Dumeril's boa. In its living-room aquarium, Satan’s alive in transverse bands and mushroom patterns of brown and gray. Ramsey feeds Satan rats. There's an empty aquarium to house his other snake, no longer here. Ramsey had to sell him off, $40 bucks. He paid $140.

In a Guinness Beer T-shirt and Levi's, and sitting on his sofa, Ramsey looks younger than his 38 years, but his steely dark eyes show lived-in days, bloodshot; equal parts desperation and kindness. He’s guarded — secrecy suffused with an inherent suspicion of others — so his personal narrative takes time to unfurl.

After graduating from Tucson’s Cholla high school, Ramsey apprenticed to become an electrician. When the economy nosedived, his days of sweet take-home pay — a steady job of seven years — ended. Put him on a collision course with life, which included a pair of DUIs.

LLife’s rarely in step with your heart but Ramsey’s on fairly solid footing for now. (“I stopped doing all the crazy stuff.") He scrapes by on unemployment and help from his dad and uncles. It’s harder and harder in his trade to find work. He lost his last job in October.

He's hopeful; there’s his electrician’s job interview tomorrow. Hopeful for his kids, his life, his loneliness. Treading water can eat a man alive.

It’s never easy to erase brutal tender years, the ingrained stuff that defines. Ramsey knows. He stares at the carpeted floor at his feet and sighs in a mild way. His own childhood is stuff of terror and loss and displacement and homelessness. Says, “you'd be surprised what a kid can pick up on.”

"I tasted weed for the first time when I was five. I could show you how to cook up heroin when I was six because I'd seen it so much.”

Phoenix-born, Ramsey never knew his real dad. Mom traded sex for drugs. "She was a biker whore to feed her habit," he says. "I saw a lot of guys coming and going.” Grandma abused him too, bad, out in San Bernardino.

One night his mother and her boyfriend were arguing. The pissed-off boyfriend, likely “high on something,” walked the 5-year-old Ramsey out to the railroad tracks near their place in Phoenix.

(As Ramsey relates the story, Sophie, his strangely beautiful pit bull-Chihuahua mix, antagonizes Junior, a larger dog confined to the patio, the other side of a sliding glass door.)

The two waited at the tracks. As the roaring train approached, the boyfriend went and put himself on the rails. The trusting little boy watched the man get decapitated. A suicide barely reported in the news.

Mom couldn't care for her boy. So she dumped him with friends in Tucson. When he showed up at school with a black eye, the cops intervened and placed the 6-year-old in Casa de los Niños, a local home for abused kids, which jettisoned him into the foster care system.

"I guess I came from a hard background,” he says. “I block most of it out of my mind." He laughs. "My mom taught me well, I could steal a loaf of bread and a gallon of milk without anybody noticing me."

Change brought some gratitude, Ramsey says. His foster parent, Robert Ramsey, a now-retired schoolteacher and pianist at a local Baptist church, adopted the boy after one year, sparing him a life in and out of foster-home hell.

And Ramsey's not holding his childhood against himself or anyone. "I never did heroin or any of that because I saw what it did to my mother. I could be fucked up on some sort of drugs." He shakes his head, “if you're going to have kids, don't be drug-addicted."

When Ramsey was 21, he reunited with his mom. The tear-filled reunion inspired his move back to Phoenix. He wanted to be with her.

"I hadn't seen her since I was six,” Ramsey says. “I wondered about her every night. And for a long time I blamed her for everything. But by the time I saw her again I didn't hold any resentment. I thanked her. Who knows where I would've been, or if I would've been here at all if she hadn't given me up?"

But Ramsey didn't jive with mom’s current boyfriend and left. He returned to Tucson, back into electrician's work. His mother died several years ago under bizarre circumstances involving a head injury. The boyfriend vanished, and Ramsey and his uncles are calling it murder. No charges were filed.

* * * *

Ramsey lifts Satan's Little Helper out of its tank and drapes him gently around his neck. As Satan snugs into place, Ramsey says, "He's got the death grip. But I could overpower him if he ever tried to strangle me."

His talking voice is softer now, but higher in pitch because Satan’s got his throat. He strolls outside and down the block to the Circle K. Everyone stares, the two kids on bikes, faces in cars. Ramsey’s seems unaware how he can frighten passersby, and insists he’s not trying to. Satan goes where he goes, like a personal history. He’s his companion. “I took him on the bus once and the driver got all mad,” he says. “He made me get off.”

A corpulent dude inside the Circle K sports a “Trump that Bitch” button on his t-shirt and too-small plastic mirror shades. He’s not pleased at the sight of Ramsey and Satan, so he huffs with righteous indignation as he pays the cashier for his smokes and twelver. He exhales extra loud pushing out through the glass doors, into the evening.

Debbie's a regular here, her long gray hair, her little Chihuahua on a leash. Satan’s incongruity, and shimmer under fluorescent lights, stops her. She marvels at his beauty, quizzes Ramsey about him. Her dog wears a sweater, speeds in circles at her feet, and growls.

Ramsey, his voice still pitched higher from Satan’s grip, politely answers Debbie’s questions. She reaches out a finger, connects timidly with Satan’s head. “Just so beautiful,” she says.