The one day he walked from his house, down the street, blood dripping off his arms, and paced around the nearby park in Torrance, California was his least favorite day in life, mainly because he'd sent a picture of his bleeding wrists to his grandma. Who'd be so alienated at 12 to attempt suicide when everything else is, at least on the exterior, relatively OK?

Later, it couldn't have been so easy pissing in the boy's bathroom. Not like that. Just think of it. The shit you'd get in high school. But the internals were harder. There was the time not so long ago when he ingested enough trazadone to kill an entire psych ward. That one nearly did him in.

What about making life into what he could imagine and dream, hardly easy for anyone. Now, at 24 years old, he should have some idea of what he wants out of life, as opposed to what he needs. The needs were figured out, long ago—not being a girl was right up there with air, water, food and shelter.

Ruminating on that need, the high-school bathroom bit seems almost arbitrary. "It wasn't that big of a deal," he says. He pauses. "I guess the first time was scary."

His slashed wrist scars are more a symbol of life continuing, evidenced by the small stick-and-poke tattoo of a semi-colon. That says everything right now. The hurdles along the way, the gender dysphoria. His loss of innocence is hardly Lord of the Flies. His loss of innocence is Emily becoming Cain, when most kids were hop-skipping through puberty. Transition as equal parts sacrifice and self-love, born of self-hate.

He won't and hasn't mourned for Emily, his South Bay childhood. Not even in some bittersweet nostalgic way.

"Absolutely not," he says. "Not even a little bit. Not ever."

He doesn't even remember much of it, like it's blank. The three sisters and two brothers, yes. His parent splitting up. A shitty step-father. But little else. Hardly even a Christmas.

Cain Pierce works a small pitcher of draft beer at twilight. After a long workday he's talking PMS in the back patio of IBT's gay bar on Fourth Avenue. He's just coming off his period, a particularly "brutal one." His 25-year-old boyfriend, Or'ion Steele—a rising Tucson (and national) pageant drag queen—shakes his head, grins slyly and flicks on his phone screen. Cain had gone years without menstruating, but since he stopped the hormones, it came back. He can't afford a hysterectomy, "but it would be nice." His insurance won't cover it, but there's the sense that the transition wasn't exactly about genitalia. A 2012 mastectomy in San Francisco removed his D cup-sized breasts. He crowdfunded some of the cost but mostly his dad picked up the tab. Other problems: Cain's losing hearing in his left ear, unknown reason. "It's going fast, within a year it went from just fine to needing a hearing aid."

It'd be impossible to guess Cain was born Emily. Testosterone injections thickened his vocal cords into a pleasing low tone. Even his burps sound truck-driver-y. His reddish jawline beard highlights blatant brown eyes, lip piercings and workday-flattened Samurai hair—shorn sides, back ponytail. He's pretty, but not in any traditional feminine way, more masculine; a young Johnny Depp only slightly heavier. He's gained weight since last year, the unavoidable consequence of quitting crystal meth. Had to. For Or'ion, for himself. He's one of those oddballs who can just stop. A white knuckler, as they say, and he's not looking back. Today he's Joe Normal in button-down shirt, black pants. He sells shoes full time, just started in assistant-manager training, $14 an hour, a good wage for Tucson.

Forget tired stereotypes of gay men mixing cliched traits of two genders—the bitchiness of women, the machismo of men. Cain's open, self-effacing, and chivalrous toward Or'ion. He covers most if not all of the couple's bills. "Things go bad we talk about it," Cain says. They share an eastside apartment but mostly stay with a friend off Fourth Avenue "because it's near IBT's. It's our home here," Cain says of the legendary bar. "We live here."

Or'ion is Cain's emotional support, and supplies the couple's "fun money." It's whatever Or'ion earns from drag shows. Some nights are good, some not so much. Not enough to live on, but it helps. His best take home was $300.

Wearing a unicorn T-shirt, Or'ion's striking with a bald head and lithesome build. Or'ion's been a dancer since he was a kid. ("I learned to dance to old Usher and Michael Jackson videos.") He's a member of Tucson's four-man HOK (Häus of Kunt), a performing-arts collective that participates in drag shows and pageants. Chicago-born Or'ion (real name Glen Anderson) arrived in Tucson via North Carolina, through his master sergeant dad, and Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. Mom's a hairdresser who, he says, "outed him" and he seems almost shocked talking about his dad's reaction to him being gay.

Dad said he didn't care as long as his son is healthy. Could've gone worse. One day he lost his Chipotle job and dad said he'd have to join the military or move out of the family house, so he left. This was the day before his 21st birthday. He met a "drag mom," and started doing his makeup and drag three years ago. His pageant wins include Mr. Tucson Newcomer and Mr. Arizona USofA. Live, he transmits sassy camp and unwieldy sexual tension. He can do perfect splits wearing high pumps.

Cain pulls from a vape, explaining how they finally met, last fall. Or'ion "claimed me at the bar. He said, 'You better go home and wait.' That made a lot of people mad. He's really hot." He's enamored and Or'ion is his first real boyfriend, "and hopefully, last." Or'ion's met Cain's dad and family near Los Angeles. Over Thanksgiving the two dressed in full drag and went out for Italian food. Dad, brothers and sisters. Night was a hoot. Cain grew up in the South Bay area of Southern Cal., Mexican-Catholic heritage. "My grandmother would bleach her skin and hair with Clorox to look whiter," Cain says. "Those were sadder times." Grew up listening to Sublime—singer Bradley Nowell was his uncle through marriage.

Mom worked a lot, four or five jobs. "My dad wasn't working, but he'd just passed the California bar." They all get on now. Went to live with his father. ("There are only so many times you can see your stepdad hit your mother.") The presentiment of wretched detachment wove itself into his kid life. "When I was born they said I was a girl," Cain says. He isolated, hard. Even fourth-grade teachers picked on him: "a few hateful ladies who had no business teaching in school." He knew he was a boy for as long as he can remember. "Nobody understood. I was a bright kid, just didn't have the support.I missed out on experiences. I was having periods by the time I was 11. I was attracted to girls, so I came out as a bisexual girl at 12." He pauses. "I didn't know what I was doing."

A trans woman from GSA (Genders and Sexuality Alliance) spoke at his ninth-grade class, his first exposure to anything trans, and it was mind-expanding. He began transitioning at 14, dropped Emily from his name. The dysphoria saw him bind his chest with Ace bandages to conceal his breasts, and occasionally don a fake penis to school (his homemade packer: a condom filled with hair gel wrapped in pantyhose).

He couldn't communicate the complexities of his experience with anyone. Self-definition came through consumer goods. "I'm not a girl so I guess I should be wearing boys' clothes to prove I'm not a girl," he says. "I had one dress in high school and it was a Dickie. Only wore it a couple of times. It just didn't work; everything was wrong." One time dad asked if he was having gender issues.

Getting beyond that consumerist mindset ain't easy for any suburban-raised American pup. "One day at the mall, dad just threw a few hundred at me, 'Fine, get whatever you want.' I was elated."

Reading brought relief. Khaos Komix blew his mind. He singles out creator Tab Kimpton, his coming-of-age queer and LGTBQ stories, as funny, dark, empathetic. Says his life would've been a lot different, if not for Kimpton. Also, Jack London's redemptive White Fang, and anything by Ted Dekker. "I loved the Circle series and Thr3e especially."

Mom wanted him to get help after that first suicide attempt. For years he was shuttled off to therapy. "I told them [doctors] what they wanted to hear because I wanted to get out of their office." At 19 he was diagnosed with "the holy trinity: bi-polar, depression and anxiety. It was an actual medical diagnosis. I still don't trust most mental health medical professionals. But sometimes I find a good one or two that do help me."

If he were a teen now, it'd be easier to identify sexuality and gender as a journey, to transition. "There's so much more visibility and resources than a decade ago," he says. "Things are very different now but we still have a long way to go to get more things in place." Gender means something different to different people. Binary, abstract. That makes it harder to grasp how many kids identify as trans now as opposed to a decade ago. But people are beginning to understand themselves at younger ages, still-forming minds, pre-puberty. UCLA thinktank Williams Institute did research. There are nearly 150,000 transgender teens—aged 13 to 17—in the U.S. right now. (That's .7 percent of the total population.) The number's rising. There are 1.4 million transgender adults nationwide. One in 137 teenagers aged 13-17 identify as transgender in our country.

For Cain's part, after he'd completed gender counseling because he was under 18, his dad and therapist signed off so he could start hormones. Dad helped with the medical research. He graduated Torrance High School, began college and took the first shot of testosterone, all the same week, at 17 years old. He enrolled at the Art Institute of California, specialty video game design. (He codes, draws, creates 3D models.)

A year or so later he's in Phoenix. Followed a crazy girlfriend there. ("I was literally raped and tortured.") Got into smoking meth. Another lover popped him, a black eye. Some emotional trauma left him unable to speak. "Yeah," Cain says, pulling from a draft beer, he's "battled worse demons." A new demon might be alcohol. Half-jokes that it's his self-medication.

He left Phoenix in summer 2015 for Tucson. He'd met a girl. He worked a slew of low jobs, and became a call center star. "It's so dehumanizing, but the money. I was in the comma club, you know, when your paycheck has a comma in it. But you can only have so many panic attacks before you need to find another job." He's worked at Chipotle, Blake's Lotaburger ("I'm in a lot of debt because of that one"), and now as a shoe store assistant manager.

Cain looks to Or'ion across the patio table. Laughs and says he was only certain that he liked men in November last year, when he and Or'ion coupled up. "He's patient with me. I still have my moments. I used to have full-blown meltdown breakdowns."

As if on cue, Or'ion offers a sitcom sigh. "I've had my ups and downs in drag," he says. "No, it's not easy being a black gay man. No, it's not easy being a black man doing drag."

They open up about their sex. Like how testosterone makes your clitoris bigger. "I mean big. It can measure four inches when I'm on hormones," Cain says. "Believe me, you can penetrate with that." When he begins testosterone again, his libido will "go crazy like a teenage boy's. It's like puberty."

Cain can't afford the testosterone, it's why he's not taking it. The hormone isn't that expensive, a couple nights out drinking, really. I mention that to him, and he sort of nods. Does he worry about testosterone side-effects, or only using when finances permit? How it thickens blood, might cause cancer, or that his health-risk profile changes to a man's, pushing up high blood pressure and heart attack risk, etc. Cain shakes his head, says emphatically the alternative is "so much worse."

Cain's off all other meds now, the anti-depressants, anti-psychotics. "Better than before," he says. There's a tattoo of circles on his back, the image of becoming whole. It's noted that Cain's parents weren't clueless. At all. Frightened, maybe. His mother suffers chronic myalgia, chronic fatigue, depression. Says his dad is dope. "Look," he says, "I've been very privileged because my dad is white, well-educated, smart, open-minded. I had a leg up. And I consider myself a life-long learner." He's surprised people don't use what's available for free. Like the Apple U app: "A Harvard psychology course? No problem." He wants to return to school, dreams of it.

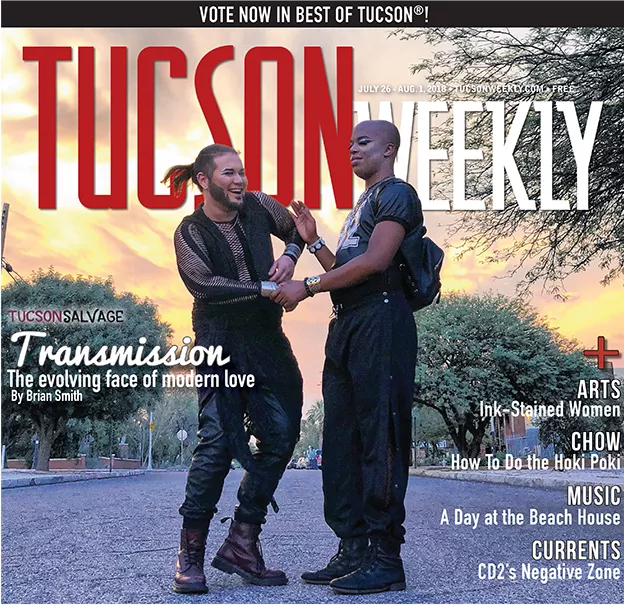

A few evenings later, Cain and Or'ion stroll around near the peak of A Mountain. They're in full drag. For photos, not hikes.

See, Cain's a drag king, stage name Rexx. Drag kings don't receive the kind of mainstream love of drag queens, yet. Did his first show September last year. Onstage his moves are graceful, slinky. Sometimes he uses sign language ("I'm not an interpreter, and I'm not fluent, I'm conversational.") He's bigger than a man-taunt of an effeminate pop star imitating a woman; his is a show of innocence and joy, a mix of compulsion and necessity. Yes, he gets nervous beforehand, extremely. He's entered in the Tucson Pride Pageant next month (August 26).

Cain's all neo-Victorian, a kind of Alice in Wonderland mad tea party ensemble, but darker. Fleshy black mesh shirt, leather boots. He drinks beer, wipes sweat from his forehead, and complains about his black leather trousers. It's around 100 degrees out, the sun's about to drop.

Or'ion mines the androgynous alien authority of a young Grace Jones, a masculine and feminine prowess, as sharp and rigid as the saguaros. He's bald and fierce, in sexuality and camp. Dressed all in black: lilac eye shadow, pink lips, black skin, bald head, highlighted in a girl's football jersey and neck rhinestones. It's hardly a wonder he's an in-demand drag queen.

The king and queen half-wrestle and laugh. An outward display of affection and interaction that a decade ago might've gotten their heads kicked in, hate-crime style. Of dozens of folks enjoying Sentinel Peak, no one bats an eye except one girl riding passenger in a Toyota pickup, rolling up the hill. A triple take and a what-the-fuck? look. Cain and Or'ion don't give a shit what anyone thinks. Or'ion helps Cain feel comfortable with his body, that's for certain. They kiss and embrace and burp and drink beer. Just a couple of pretty regular dudes.