When Frost, the Chicano rapper from East L.A., watched Orson Welles' 1958 film Touch of Evil, he identified with Joe Grandi. The portly mustachioed jefe of the narco trade in Los Robles, Mexico, Grandi was running drugs with the help of Hank Quinlan, a corrupt U.S. cop on the brink of self-destruction. On his 1997 song "Mexican Border," about an East L.A. drug dealer who blasts a cop on his way down to the border to pick up a shipment from Sinaloa, Frost samples Grande in the midst of a rant against Charlton Heston's Mike Vargas--the Mexican cop who crosses his own border by taking a blonde, white woman for his wife.

"He's got a reputation," Grande squeals. "He's gonna leave this town wishing he and that wife of his had never been born!" As the sample fades, the beats kick back in and Frost announces that he's "a mean motherfucker."

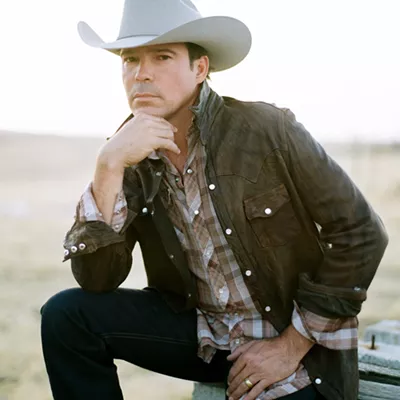

Tom Russell, the white blue-collar troubadour who was raised in West L.A. but now lives in El Paso, is also a Touch of Evil fan, but when Russell watches it, he identifies with Quinlan. On his new album, Borderland (Hightone), Russell sings "Touch of Evil," an ode to the scene in which Quinlan--all sweaty, fat, and chocolate-bar grotesque--visits a Los Robles whorehouse and asks Marlene Dietrich to tell him his future, only to find out that he has none. In his song, Russell's girlfriend has just left him, and he's sitting in a bar across the borderline in Juarez nursing "the Orson Welles/Marlene Dietrich blues."

The border may be where Russell lives now (he irrigates his land with water from the Rio Grande), but throughout Borderland, he sings about it as little more than a metaphor for, as he puts it, "the borderline between a woman and a man." Russell sings about a "brutal little war," but it's not Touch of Evil's war between nations, men and competing drug economies, it's a war between hearts. "The night my baby left me," he sings, "I crossed the bridge to Juarez Avenue."

In most gringo folk and country songs about love across the border, the men are usually white, usually outlaws, and the women are usually from "old Mexico," usually have dark eyes, and are usually treacherous and seductive--south of the border Venus' flytraps who destroy drifters and cowboys by making them fall in love in the back room of a dusty cantina. It happened to Dylan's New Yorker back on 1965's "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues," who got "lost in the rain in Juarez" and ended up hooked on its drugs and eaten alive by its women. "They got some hungry women there," Dylan wheezed, "and they really make a mess out of you." Melinda, a bilingual prostitute, was worse: "She takes your voice and leaves you howling at the moon."

The guitar-strummed archetype of the deadly Mexican woman, though, belongs to Marty Robbins, the Arizona-born grandson of a Texas Ranger whose 1959 song "El Paso," the smash from his Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs album, earned him a plaque in the El Paso airport. Robbins tells the story of a rugged prairie gunslinger who falls for the "Mexican maiden" Felina in an El Paso bar. She is "wicked and evil while casting a spell" and when he catches her talking to a cowboy, the cowboy ends up dead. After trying to escape, Robbins' outlaw can't break Felina's spell--he comes back to the bar and is gunned down by a pack of cowboys bent on revenge.

Russell's "The Hills of Old Juarez" is inspired by Robbins but it puts a contemporary spin on the fall of the white outlaw at the hands of a Mexican woman. Russell's Felina is Inez, the granddaughter of an El Paso Mexican who watched Pancho Villa hide from Pershing in the Juarez hills. In order to support Inez, Russell's drifter starts running coke in those same hills with a reservation Indian who sells him out to the cops. He ends up in Huntsville prison dreaming of the "dark-eyed girl" who pushed him into the Mexican hills that cost him his freedom.

There may be some new elements to Russell's take on Juarez--the narcotraficantes in the hills, the urban working-class consciousness he brings as a former truck driver and wood-chipper who was in Watts when it blew up into a racial revolt back in 1965--but in the end, there is little of present-day Juarez here. It's mostly the Juarez of a mythologized past.

On "When Sinatra Played Juarez," the uncle of Russell's girlfriend, Tommy Gabriel, even gives it a timeline: "Everything's gone to straight to hell since Sinatra played Juarez." Back then, during the "golden years," Juarez was about cheap divorces, tuck-and-rolled Pontiacs, dog tracks and Hollywood tourism. Now it's just a place for a broken-hearted gringo to raise a glass to Orson Welles and get back in touch with the evil lurking in his own soul.