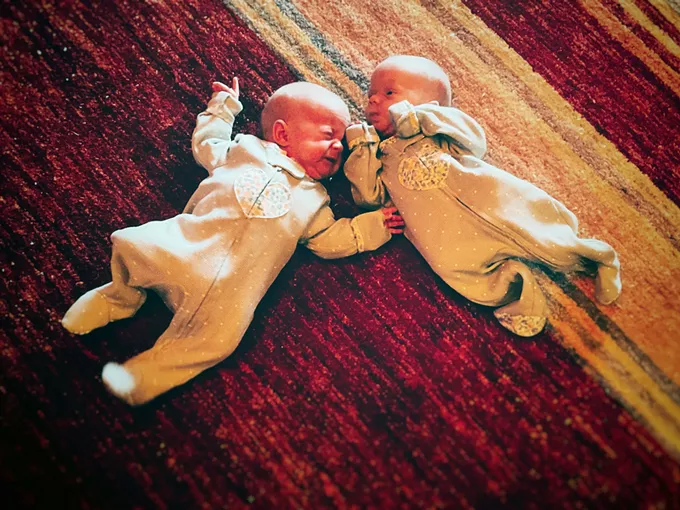

Ava and Nora, our identical twin girls, are splayed out on a blanket in our living room wearing heart-festooned size-0 onesies.They scooch to find each other’s touch. Theirs is an unyielding bond carried over from a single placenta in the womb.

This overwhelming rush of love and longing carries the hopes of a future.

It is in the smell of new baby skin, in the soft touches of the fingers and wrinkly folds of skin and in the slight chest rises. It is in the underwater haze of four deep-blue eyes, endlessly searching.

We got our girls home, and they are now healthy and blooming, finally free after six or so weeks inside their noisy little prisons, the tubes and troubling apparatus, the pokes and proddings of their six-week stay in NICU, the neonatal intensive care unit of a local hospital.

After long moments of mutual squirming, Nora and Ava reach each other on the rug, and I swear Nora manages a smile.

Soon, prescient warnings invade the spark of this lovely moment. What have we wrought upon the world or the world upon them? My head fills of the obvious horrors—climate change, pandemics, child-murdering wars, sociopolitical fuckedupness, financial challenges, and food shortages in a world where the two largest economic bankrollers are war and sickness. How I’m an old dad able to survive my own mortality, but, I tell myself in unvoiced grief, the end is just another beginning. All these things we tell ourselves, a warming glow in the dark, even while staring into the eyes of just-born identical twins.

My wife, Maggie, spent weeks raging against doctors and systems and inane unnatural protocols of our premature babies in NICU. Her tender wounds showed up in unvague ways, lopsided toward grief, sleeplessness and anxiety. Her natural way of breast-fed rearing and skin-to-skin bonding threatened. She survived the away-from-home babies with twice-daily, long-hour NICU stays and feedings, and gentle, hushed singsongs into the ears of Ava and Nora.

Few things are as painful as watching a mother who can’t be with her newborns 24/7 in the weeks after birth. But I know we are lucky; for one, a quick-handed and brilliant doctor saved Nora’s life during delivery. But I think of a fentanyl preemie in the ward, peaceful as a drowsy lamb but kept alive on beeping machines, her brain lost to nebula. Her grieving grandparents, arm-in-arm, gazing down into the incubator. I think of children getting blown to pieces in Gaza, their mothers bearing witness.

We had to undo things the hospital inflicted on our newborns, the wretched, one-size-fits-all “care,” the formulas, the blood tests, the male doctors overriding a mother’s concern for her preemie girls, and we were amazed by how shoddy the instruction can be, advice that made our gifted pediatrician, who has nothing to do with the hospital, balk — from unnecessary blood-transfusions, cow’s milk, corn-starch-rich baby formulas (one of which sponsors the NICU unit) and other things that can have grave effects as the child grows older.

When it comes to the things they put into baby bodies, sometimes the most unnatural, counterintuitive and counterproductive did nothing but give our girls rashes and constipation, fevers and high heartrates, alongside potential organ problems.

To counter, they attempted to administer further treatments to fight said ailments, a reciprocal cause and effect, a vicious circle. But the simplest answer seemed the hardest to push through: pure breast milk.

Maggie mostly won the child-care disagreements, a few of the seasoned nurses, who are also mothers, stepped to her side. But there shouldn’t have been any disparities. Relying solely on individual doctors overseeing our twins, with minimal communication between them, posed real risks; blind trust could’ve led to catastrophic results.

What really got our babies healthy basically came down to nature: the force of unjaded motherhood and the power of the breast.

Maggie is a force of nature. Yes, there was the recent painful and problematic birth of the twins. I stand helplessly by and watch her as she meticulously measures continuous flows of milk pumped round-the-clock from her breasts, which will continue until the twins latch on to her fully. This, as she maintains breast-feeding our other two daughters. The careful eating and supplementation of her vegan diet, and the large amounts of water consumed. The aches and pains and sleep deprivation, all while balancing chaotic family (five children now) and motherly duties, alongside her other work and school studies. There ain’t a man on Earth who could do this.

What lifts my soul, and Maggie’s, is the knowledge our children will be better for it.

We just celebrated Hanukkah (my wife is Jewish), and it is nearly Christmas now. The true holiday gifts are Ava and Nora, which sort of defines both holidays for us in the grand ideas of warmth and family and home. There is no escaping our goddamn good fortunes in a world of sorrows.

I might be consciously (or unconsciously, hard to tell) mourning a world we’re losing; I find hope within these very folds of baby skin, using empathy, sympathy, humanity and gentleness toward nature as guides. It always comes down to the simple shit.

A yellow-eyed old-timer back in Detroit A.A. rooms could distill his hard-won life lessons to their bare essentials. His wife had died, his son had died. He found peace.

I remember him telling me once, “Man, this is all so damn easy. If it sounds corny, tough shit, brother. God or no god, you just gotta do it.”

This is a cycle that has long been fixed.

Brian Smith's collection of essays and stories, Tucson Salvage: Tales and Recollections of La Frontera, based on this column, is available now worldwide on Eyewear Press UK. Buy the collection in Tucson at Antigone Books, 411 N. Fourth Ave. You can also pickup his collection of short stories, Spent Saints (Ridgeway Press).