At mid-century, Paul R. Williams was a sought-after architect in Los Angeles. Known for his luxury houses for Hollywood stars—among them Lucille Ball, Frank Sinatra and Bill "Bojangles" Robinson—Williams could make houses in almost any style, including the popular "California Spanish" genre. But he gave these works a distinct modernist cast, with simple, elegant rooms and patios that allowed indoor-outdoor living.

A great irony of Williams' work is that he would never have been allowed to live in the houses he designed. Williams (1894-1980) was a Black man—the first black architect to be installed in the American Institute of Architects—and the grand houses he built were mostly in neighborhoods that practiced legal segregation. African-American residents were banned from living there.

But Williams did more that build homes for the rich. He designed government buildings, a cathedral, churches and hotels—and public housing projects for people of modest means. He once declared, "Expensive homes are my business and social housing is my hobby."

In 1948, that passion for "social housing" brought the respected LA architect to Tucson.

Developer Del E. Webb hired Williams and an LA colleague, A. Quincy Jones Jr., to design a massive affordable housing project in Tucson. There was a shortage of houses after World War II, and Webb planned to build several thousand modernist homes for people of modest means. Now 72 years old, Pueblo Gardens, as it's called, is one of the mid-century neighborhoods on the Tucson Modernism Week self-guided tours this weekend. Visitors to Pueblo Gardens, located south of 22nd Street and east of Kino Boulevard, can see how this experiment in modernism has fared.

Tucson Modernism Week has had to go mostly virtual this year, thanks to COVID, says Demion Clinco, CEO of the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation, sponsor of the popular 9-year-old event.

"We had to cancel our spring home tour of ranches," Clinco says, and he realized quickly that the autumn modernism celebration had to be re-imagined. The popular annual home tour of mid-century modern houses has gone online, and so have the lectures by architecture scholars and exhibitions put together by University of Arizona Museum of Art (see details on the right).

A new category of self-driving tours, though, takes people away from their computers and sends them tootling around town; they can check out sites from inside their cars or stroll along the sidewalk. The five tours cover modernist churches, neon signs, the commercial districts of Sunshine Mile, Miracle Mile, and mid-century modern neighborhoods. Tour goers can sign up online to get a free written guide about each place, arriving via downloads.

An ambitious menu of 15 to 20 neighborhoods brings tour-goers to subdivisions.

Tucson built a "high volume" of suburbs post war, Clinco says. On the tour you can see the glamorous Wilshire Heights on the east side; middle class Broadmoor in midtown; and Indian Ridge Terrace at the edge of the foothills, complete with a Hohokam archaeological site.

Pueblo Gardens, the one that brought Williams to town, is far more modest than most of the neighborhoods on the tour.

The project was billed as an effort to provide decent housing for working families after the hard years of World War II. The development got national attention, with write-ups in Life magazine and other outlets. Not only would the houses be affordable, their designs, fresh and modern, would signal a new era of "American optimism," Clinco says.

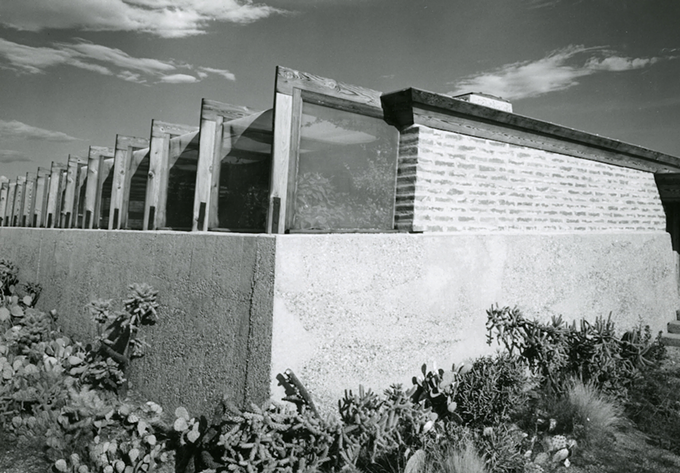

Williams and Jones designed one-, two- and three-bedroom houses, ranging in price from $5,000 to $8,000, according to an informative article by Elissa Schirmer Erly. Modest as the houses were, their modern features were attractive. Walls of windows and patios created indoor-outdoor living; roof overhangs muted the fierce sun. And the wood frame exteriors were novel to Tucson: the architects ordered "California redwood combined with plywood or stucco painted with bright desert colors," Erly writes.

But the optimistic project did not succeed. Only 750 homes were built, instead of the planned 3,000, and not even all of those were sold. The leftover houses eventually landed in the hands of the Federal Housing Administration. Promised amenities were abandoned; people who bought into the neighborhood had to fight for years to get sidewalks and street lights.

Scholars speculate that Webb's project failed because too many builders had rushed to create new post-war housing. And in any case Tucsonans were already drifting away from the center of the city, moving toward the new red-brick eastern suburbs.

Ironically, a project that offered the promise of a home to people without a lot of money had the same racial codes as the rich white neighborhoods in LA. In early years of Pueblo Gardens, only whites or people of "Caucasian race" were allowed to live or buy a house there. As with so many of his projects, architect Williams himself would not have been welcome.