My 1-year-old daughter is hunkered down, collecting gravel and dropping the pieces into one of many handmade luminaria bags. She does not understand how the bag is suffused with import, the pretty star and moon cutouts tender astral nods to our fallen friend. Suddenly his mournful refrain rises over her, an almost biblical chorus, "And though I once was rich/I know what it is to be hungry..."

Rickie is playing with another little girl and my pregnant wife keeps watch over them, saddened in the final-respects assembly of friends and family as much as she is joyful of a new life growing inside her belly. Rickie rises, waddles and stumbles along in the unpretentious Scottsdale backyard, around legs of the socially distanced and masked up, oblivious to any death and the familial closeness of strangers. She catches up to what drew all of her attention, a little dog named Bill, belonging to a man who attended Coronado High School with Lawrence. Bill makes Rickie laugh and he licks her and she coos like a dove and the warm December sun shines down hard.

The refrain comes around: "Though I nearly drowned/I know what it is to be thirsty..." It is a song that offers the gathering both a rebuke and definition of lingering sorrow. It is one of the greatest songs sung by easily one of greatest singers ever from Arizona. The song is The Pistoleros' "My Guardian Angel," its singer Lawrence Zubia, who died last month.

***

One of Lawrence's three kids, 19-year-old son Jack, is beautiful in the way his dad was, the cheekbones, the kindness, a mere presence that demands attention. He welcomes guests to his dad's remembrance offering food and water. He listens raptly to stories of his father. I remember Lawrence telling me about Jack, "He's so worldly. Well-traveled, well read. He is the perfect candidate to continue our legacy as an artist/musician."

Lawrence and I were both singers in rock 'n' roll bands when I met him, around 1991 or thereabouts. I was always fascinated with him. We divvied those romantic ideas of the written word and rock 'n' roll and we had lots of shit in common, including addictions and depressions, and that turned to other things in common in later years, like fatherhood and overriding senses of gratitude, which dominated our more recent communications. I'd go months not hearing from him and then he'd pop up sending these long missives full of love and selfless support, and writerly anecdotes, observations and updates involving the world around him, the handyman gigs he did to survive and provide while his songs were getting used in television shows. His solo gigs he'd play a few nights a week, which designed his world around the amenity of being there for his kids. "You want to be a good parent?" He'd tell me, "I learned early the hard way. You just have to be there."

Years ago, Lawrence discovered the body of our mutual friend Doug Hopkins after he shot himself, our generation's tragic sacrificial lamb, and we talked about "luck" being involved that we didn't do same.

I remember Lawrence's detox-ward stints and stitches, the cops literally chasing around, the grinding through the giant '90s-money of the major-label record and publishing machine. How he came out about the molestation he suffered at the hands of his uncle-priest. How he nearly died a number of times, for a number of reasons, all of which could be whittled down to depression. He swore his children saved him, became his life, and I believe him. He always said, "once you have a child, suicide is off the table." He was their biggest cheerleader.

In the service, his 11-year-old daughter Toni talks of the children's book series Stick Dog. How she wanted him to read one to her one night at bedtime, and so they went out to the bookstore to get it, returned home and they laughed and laughed along with the book.

Twenty years ago, I wrote this in a piece I did on Lawrence in Phoenix New Times, when his first child, Daniela, was a baby, and the romance is there: "What makes Lawrence's current lifestyle all the more remarkable is that he's a man who got into rock 'n' roll believing that life held nothing else for him. It was a foregone conclusion that he was predestined to write songs and front a rock 'n' roll band until the day he died."

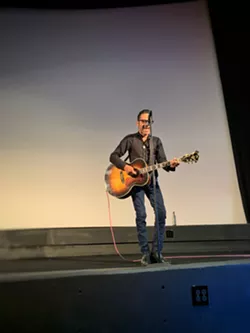

Well he died, pneumonia, while recovering from pancreatic surgery. Of course, he was fighting for his children and partner at the end. And his band, the too-tough-to-die Chimeras/Pistoleros celebrated their silver anniversary three years ago. Last time I saw Lawrence play live was at one of my Tucson book readings a couple years ago. He strummed a Doug Hopkins song.

We pedestalize our dead friends. When people die we say things, things that may not be true, attempts to get at the basic notions that make us who we are, which can only be guessed at. There is a spark inside sometimes, its genesis we haven't a clue. We are lucky when the spark becomes flame, but where does that flash and heat originate, and, more, how do we harness it? My buddy Lawrence Zubia was forever searching for such answers. At least some kind of explanation. Dude was all about the spark and the flash, because that is where his songs lived. It is also where the bad shit lived too. He learned to employ the heat, going there for the music but not the destruction. Such maneuvering and grasping ain't easy, and I've seen precious few manage. Even his love songs were deceptively layered confessionals, merciful with slight airs of indignation and moral grounding, as they should've been. He could never slip into the maudlin.

In this remembrance people spoke personal truths, no prattling of inconsistencies, only the solaces that belong to them. Band members who'd backed him for more than a quarter century, the guitar crunches and heartbreaks, the solidarity and triumphs, the jests and the brotherhood, because here was a guy, and everyone knew this, who had that ability to turn ugliness to beauty, whose life benchmarks were so absorbed into him there were no dividing lines, and it took outsiders to remind him how those wretched or beautiful landmarks blended to become pivots of his generosity of heart. When the bad becomes the beautiful. How a gifted working-class kid who played mariachi music at 12 years old with his father becomes a self-destructive vulture, becomes a mad accomplished angel after emerging on the sober end of living and love.

He became a spindly titan of earned insights and perceptions, wholly self-aware, wounds and all. Sartorially, always a romantic timeless outlaw, which he cultivated to a degree, with the coal-black, spiked or slicked hair and overall élan of some kind of young Hispanic Keef meets Kris Kristofferson, reflective of the easy, stay-free extension of his inner-self. He was an original. Like many of our mutual friends, the truths he mastered had no real application in a for-profit work-a-day world—generosity, soul, song, fatherhood.

He'd grown into family. His awareness of his own mortality came out in conversations usually about his children, peppered with Tibetan sayings or a Merle Haggard line. Or he'd say something hyper-encouraging, like "that's why we're here. To knock it fuckin' out."

Listen to his songs and his secrets to living are there, "I'm concerned that I'm not concerned ... Suicide gives me a ring/Checking in on how I've been." Listen to his 22-year-old Paris-based daughter, Daniela Zubia, and her take of Kristofferson's "Sunday Morning Coming Down," or her own "Country Song," for that same melancholy sparkle, father-to-daughter.

Lawrence's younger brother Mark is gifted songwriter and guitarist, their deep brotherhood easily heard on their albums, in their songs. Their relationship rivaled Chris and Rich Robinson, filled of love and fights and separations and reconciliations. I played in a band with two brothers, saddled with my own tenuous grasp on reality, so I understand the defenses, respect and regrets.

Lawrence's mother, the gran matriarca de la familia, Amalia speaks to the gathering, rekindling things in tears and laughter about how Lawrence had never resigned to be held in one place. How Mark, as a boy, would search out Lawrence's poetry to turn into a song.

One thing I know for certain about Lawrence, when he wanted to die, he lived. When he truly wanted to live, he died, with so many unfinished dreams involving his children and partner Anne, and in song.

***

My daughter and my wife and the dog named Bill and Lawrence's loved ones and the sadnesses. I sit under the backyard umbrella at this memorial, overtaken by some inexplicable temporary grace and that sense of endless enclosure when a good friend dies, the strange way neighboring palm trees become lonely guardians of dirt alleys, the repeating walls of backyards varying only in tones of gray, the arrangement of Lawrence images filling an altar against the house. I see him on stage, that stance with hands behind him, chest forward, as if leaning into a headwind, his beating heart leading the way, as close to some fuckin' Old Testament seer as a rock 'n' roll singer can get.

My mind wanders to the others in my little orbit who died in 2020, these fellow travelers, old band roadie/sidekick Greg Cox, the young and gifted Sarah Shelton, writer/funnyman Corey Hall, singer Richard Flower, poet Isaac Kirkman, all human originals whose lives were textured in ways not easily understood, so known to anyone who loved them yet inexpressible to a stranger.

My daughter Rickie breaks the trance. She waddles up, big grin, unguarded eyes. A fetching ensemble of purple flowered dress, heart-festooned baby socks and diaper. When she reaches my knee, she lifts up her hand and it contains a gift, a handful of gravel, a Lawrence Zubia memento, which my wife, with her big belly filled of new life, intercepts before spillage. She slips the small stones into my jacket pocket.