The story he needed to tell was about a forgotten slice of Tucson's history, a story about a proud but stepped-on community, a story about unlikely heroes who overcame insurmountable obstacles. It was a story about his great-grandfather, Ramon Jaurique, an orphan and World War II vet who spearheaded the successful efforts of the indigenous Pascua Yaquis in the 1970s to gain federal tribal recognition, ownership of their land and fight off the onslaught of bulldozers to raze their homes to build a freeway.

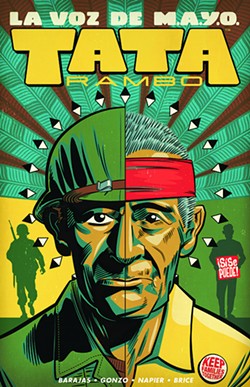

Now after several years of pondering, researching, interviewing and writing, Barajas' story about his bistata is told in the graphic novel, La Voz de M.A.Y.O.: TATA RAMBO, with illustrations by Mesa-based artist J. Gonzo. The book, which was featured at the recent Tucson Comic Con and is available in comic shops and bookstores, is published by Top Cow Productions, a division of Image Comics, Inc., one of the country's leading publishers of comic books and graphic novels.

In TATA RAMBO, Tucson-born Barajas reclaims the ignored and undocumented history of the Pascua Yaquis and activists like Jaurique who co-founded the Mexican American Yaqui Organization (M.A.Y.O.) in 1969. The 30-year-old Barajas, who worked for the Tucson Weekly and the Arizona Daily Star and performed stand-up comedy at Laffs before relocating to Los Angeles, based his research on interviews with his Tata Ramon, family members and Yaqui elders, and the few and invaluable documents such as the M.A.Y.O. newsletters and local newspaper clippings.

The Yaquis, who call themselves Yoeme, lived in Sonora and Southern Arizona in pre-Columbian times. The Yaquis fled violence and oppression in Mexico at the turn of the last century, establishing settlements in Arizona, the most notable, Old Pascua, near West Grant and North Oracle roads. Today the Yoeme have communities in New Pascua, on the city's southwest edge, in Marana and in Guadalupe, near Phoenix.

But more than being about local history La Voz de M.A.Y.O. is the one of the few graphic novels published in this country devoted to restoring historical truth to indigenous and Latino peoples. In the 1970s, Mexican political cartoonist Rius' gained a strong following with Cuba for Beginners, followed a series of For Beginners series. Then there is A Most Imperfect Union: A Contrarian History of the United States by cartoonist Lalo Alcaraz and writer Ilan Stavans. And this year, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the Freshman Force, was published as a 52-page comic anthology.

"Over the decades, comic books by and about people of color have become an important space as corrective to an otherwise straight male, Anglo-biased historical record," writes in the book's foreword Frederick Luis Aldama, a professor and author at Ohio State University, and editor of Latinographix which publishes Latinx graphic fiction and nonfiction.

And the book—which begins with a protest and ends with a win—just may be the first of its kind in which an author documents his indigenous-Latino family's history alongside sweeping social political change.

While researching and writing the book, Barajas said it closed a void in his family's life.

"It was like saying goodbye to Ramon," said Barajas, director of operations at Top Cow Productions and who spoke on a panel at Comic Con along with striking colors and artwork by Gonzo, creator of the comic book series, La Mano del Destino.

TATA RAMBO also finally recognizes the critical roles that Barajas' great-grandfather and his colleagues played in giving dignity to the Pascua Yaqui.

"There are all these people who were forgotten," Barajas added.

Throughout his journey with the book, Barajas kept asking the question why his Tata's role as a leader and the work of M.A.Y.O. had been obscured. A satisfying answer has yet to be found but Barajas discovered a partial explanation in conversations with Jaurique, who died on Oct. 11, 2017, at the age of 88.

"I asked him why didn't you ever get credit for it and his response was 'because it was the right thing to do.' I think a lot of that had to do with him going to World War II and seeing the recognition everyone gets but also knowing you didn't do all the fighting. He didn't talk about war. He didn't talk about his past. He was a private quiet individual. Thankfully he was such a prolific writer, I was able to mine what I thought was relevant for the book."

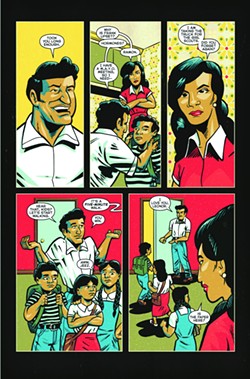

The three-chapter story begins with Barajas and his Tata attending a March 2015 rally, then travels back to 1945 in Okinawa where Jaurique, a U.S. Marine, is wounded, and moves forward to 1969 to the Yaqui rez where Jaurique and his wife Leonor are raising their family.

Barajas follows his Tata galvanizing the community, establishing M.A.Y.O. and working with other Yaqui leaders, such as tribal leader Anselmo Valencia, as well as Congressman Mo Udall, who led the effort in Congress to grant tribal recognition to the Yaquis. Here, Barajas corrects the historical record to document Jaurique's critical role, which had been overshadowed by the larger-than-life Valencia and the revered Udall.

"Mo Udall gets the credit," said Gonzo during the panel presentation. "He walked this into Congress but he's not the one who did the fighting. He just got to take the victory lap."

The Pascua Yaqui, received federal recognition on Sept. 18, 1978.

In addition to fighting for Yaqui self-determination, Jaurique was a leader in the Model Cities, anti-poverty program, helped create El Rio Community clinic, and forged other tribal self-determination and education efforts.

Barajas financed the book through a $30,000 Kickstarter crowd-sourcing campaign and as he begins promoting the book at various comic cons and book festivals—last week he was in London—he and Gonzo are looking to libraries and schools to put the book in the hands of a wider audience.

Said Barajas: "This is kinda entertaining. This is like oh wow, Mexican and native people get a win. People should see that—once. We see our people face down in ditches and we see them in cages. Why can't we see them win for once?"

Tata Rambo was a humble man, who shunned the spotlight and dismissed accolades. His Tata died before Barajas finished the project.

"He didn't ask for it," Barajas says. "I think he would have loved it. Yes his intentions were in my heart and his words were in my head for four years. I hope he would have been proud."