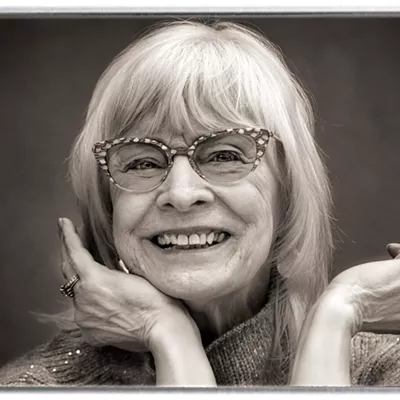

Sandra Muñoz, a mother of two, was evicted after missing one rent payment on a tight $18,000 annual budget. She worked full-time, but was out sick for two weeks, then everything went downhill.

"I had to move in with family and thankfully for them I was able to get back on my feet," she said at the forum. "But it took me about six months and I had to move into a place that was not habitable for me and my kids, but I had to move in there because it was the only option that I had."

Muñoz now works as a community advocate to help other young mothers who face similar situations. One of the biggest things she learned from her eviction experience was to understand her rights as a tenant.

"I'm just here to kind of let the word be out that you can get back up on your feet," she said. "We have a lot of good people that are not going to judge you or make it hard for you, they really genuinely want to help."

Muñoz is just one of many Pima County residents who has faced losing a rental home. Between 2015 and 2018, more than 13,000 Pima County renters were faced with an eviction. At a forum last Thursday evening, housing and community leaders convened at the Joel D. Valdez Main Library to share insights on the housing system. They argue that a large factor of the high eviction rate is laws that are currently in place, and not so much a fault of the individual tenant.

There are 940,000 tenants in Arizona, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Roughly 215,000 of them are considered "extremely low-income," which is classified as a family of four living on $24,000 per year. The income required to afford a two-bedroom rental at fair market value is $38,000 per year.

The NLIHC reports that for those 215,000 people in Arizona who need affordable rental housing, there are only 55,000 affordable rental units available. Kim Fitch of Nicolosi & Fitch property management company said there were 1,223 new apartment units built in Pima County this year, and only 3 percent of them (40 units) were designated affordable housing.

In addition, 54 percent of those units are student housing, which are typically high-density apartment buildings with expensive monthly rates marketed exclusively to college students.

The minimum wage in Arizona is $11 per hour. A person with that wage must work 56 hours every week to afford a modest one-bedroom home at fair market value. In Tucson, the average wage required to secure housing is $16.42.

As a result, renters end up paying more than the recommended 30 percent of their income on housing. With most of their income dedicated to rent and utilities, and many renters living paycheck to paycheck, just one interrupted work week is enough to throw someone into housing instability.

Stacy Butler, director of the University of Arizona's Innovation for Justice program and co-founder of Step Up to Justice, explained just how fast a responsible renter can fall behind on payments and subsequently be evicted.

She said if a tenant becomes sick, has car trouble, has a child they need to care for, or any other reasonable life interruptions, they end up missing a full paycheck. With no cushion, they can't make their rent payment, and late fees follow.

The landlord and the tenant may try to resolve the issue on their own, but if no agreement is reached the landlord can send the tenant an eviction notice, leaving the tenant just five to 10 days to correct the issue.

If they can't come up with the money in that short window of time, a complaint is filed in court. A court date is set, and the tenant is served a summons five days before the hearing. The two parties then go to court, where a judge rules in favor of either the landlord or the tenant.

Butler said 80 percent of tenants do not appear in court for their eviction hearings, which is because of a widely held belief that they will lose anyway, so taking more time off from work just to lose in court is counterproductive to their financial situation.

That belief is not misplaced, since 95 percent of eviction hearings are ruled in the landlord's favor.

Roughly 90 percent of evicted tenants who do appear in court do so without legal representation, Butler said. In eviction cases, a court-appointed attorney is not required by law, so tenants must either pay for their own legal counsel or represent themselves. But having a lawyer present can make all the difference.

"New York just became the first jurisdiction to mandate legal representation for all tenants," Butler said. "Their early data shows they're delivering an 83 percent success rate; 83 percent of tenants who are receiving legal representation at their eviction proceeding are able to remain in their homes."

Step Up to Justice organizes free legal representation provided by volunteer attorneys to low-income renters facing an eviction.

While there isn't one all-encompassing law that can be enacted to solve this crisis, Butler said policies that improve wages across the board, provide more affordable housing options and educate legislators about the true costs of evictions to the community would make the difference. This requires putting tenants and community advocates in a position to steer policy-making decisions.

House Bill 2358, which is currently pending in the Arizona Senate, would allow a landlord to evict a tenant for not paying rent in full even if a portion of the rent is covered on time by a third-party assistance entity such as any of the organizations present at the forum.

Butler said it could cost $30,000 annually to house a homeless family, but it could cost just $2,000 to provide rental assistance to a family that is about to be evicted, and allow them to stay in their home.

"In addition, job loss, reshuffling children to new schools, chronic mental and physical health issues, just this ripple effect that begins to happen once you've entered into the eviction cycle," Butler said.

She sees the eviction problem as predictable. With the use of data analysis, signs of a looming eviction can be identified two to three years in advance through falling credit scores and rising debts.

"There's plenty of data and information out there that we can utilize to identify populations at risk of eviction and engage with them sooner," Butler said.