The artist can see the whole crazy town from here: the patchwork of crooked streets snaking up the steep hillsides below, the cottages precariously perched on cliffs, the copper-colored mountains and canyons soaring up above.

It's a perfect location for an artist. And there's no mistaking that this is a house where art is made.

"You know what Picasso said," Breault says cheerfully. "A work of art is never finished. You just have to do it and let it go."

So when Breault steps away from a painting, she starts slapping together a clay mask. Or she fires up her kiln, or cuts out one of her paper dolls from handmade paper. The muñecas de papel, she says, hearken back to the ancient papermaking technology of Veracruz, where "women pound bark on stones and hire a shaman to cut the paper. It's used ritualistically to ensure the fertility of the earth and ward off evil spirits."

The art, much of it inspired by myths and rituals, mostly stays right here with her.

"I'm not interested in selling," she says.

The ceramic masks hang outside, on the patio inside a jungle of flowering plants and exotic fruits. A kiln stands in the yard and, up a little slope, a freestanding studio is crammed with drawings and paintings. And she keeps work by friends, too. Out front, Ben Dale's metal sculpture of a woman warrior rises up over the driveway. Nearby, his concrete body cast of another woman lies in the grass.

Even the house is an eccentric work of art. It started out as the stone studio of the late artist and writer George Sellars, Breault says, and when she and her husband, Ted, got hold of it, they built a second floor on top. A spiral staircase connects the two levels, and as you move carefully down the steps, you get dizzying views of Breault's myth-drenched oil paintings plastering the walls.

Sellars, Breault explains, was a buddy of the late Ted DeGrazia. A couple of Sellars' Western paintings are in the local courthouse.

"He did pointillist cowboy art," she says. "I can feel his spirit here."

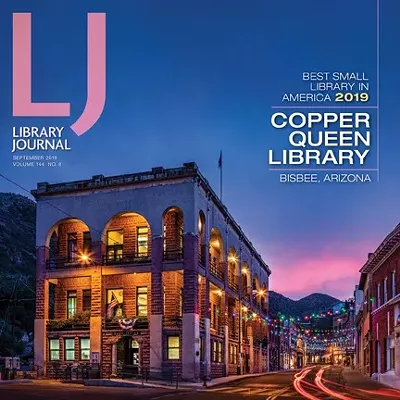

Cowboy pointillism doesn't raise a single eyebrow in this mile-high city. It's a once-and-future copper mining town that's filled to the brim with artists, musicians and poets.

What people come for, besides the art, is the "alternative lifestyle," says painter and printmaker Mina Tang Kan, owner of Tang Gallery. "It's very liberal. There are a lot of Democrats. Somebody said Bisbee is an island of liberalism in a redneck state. There's a live-and-let-live philosophy."

Nobody minds when a gay Bisbee Pride celebration takes over the downtown of Old Bisbee for a full weekend, as it did in mid-June, or bats an eye when a graffiti artist splatters Che Guevaras on walls all over town. Art cars decked out with plastic dolls ostentatiously roam the streets. Galleries joust for storefront space on Main Street, and if you pay attention, you might just come across the West Texas Millionaires rehearsing their country-twanged rock in a street-front room on Brewery Gulch.

A couple of the visual artists living here have big-time art reputations in New York and elsewhere. Painters Peter Young and Alex Hay both made their reps back in the '60s--Young for his dot paintings, Hay for pop-art-married-to-realism, as one critic described it. But they retreated to Bisbee back in the '70s. They've both made comebacks in recent years and are showing internationally. Here in laid-back Bisbee, though, they like to live under the radar. (Another former Bisbee-ite, Chico MacMurtrie, hurtled into the big-time with his cutting edge "amorphic robot" art.)

Alongside these highly regarded abstractionists are homegrown folks like Gene Elliston, who never drew until she stepped into art-mad Bisbee back in 1978 with her husband, who came to work as a lawyer. The couple had decided they wanted to raise their three children in a small town.

"I got to know a lot of artists, and I began to do art," Elliston says. Now a sexagenarian, she makes colored-pencil portraits of Bisbee streetscapes and shows them in the humble Subway co-op gallery.

Tang Kan was already a longtime painter and printmaker when she turned up in 1994 from California.

"That was the year of the earthquake in Northridge," she remembers. "That did it. I was terrified."

She moved into a house she already owned in nearby Sierra Vista, and began teaching at Cochise College. Her own work tends toward lyrical abstraction (she has a piece in the Mujeres show at Raices Taller in Tucson), and she's kept her 7-year-old Tang Gallery afloat with a colorful mix of abstraction and landscape and figure-painting.

"I don't have anything I don't like" in the gallery, she says.

Painter Michael Cadieux is a high flyer who sells his work mostly outside of town. "I have a couple of collectors in the Midwest who buy every phase I do," he says. And another collector is coming to Bisbee soon to see his giant "Baby Buddha," a gridded painting of a baby's face, based on a Wal-Mart photo.

Cadieux was still teaching at the Kansas City Art Institute when he serendipitously found his way down to Bisbee.

"I was trout-fishing in Montana," he recounts. "A guy drove up. I told him I was looking for a warm place. He said, 'Bisbee, Arizona.'"

Cadieux came right on down, in 1976.

"When I got here, it was wonderful! I love history. I love the weather. I had no idea about art happening here, but I was glad it was happening."

Seven miles from the Mexican border, the old mining town is loaded with artist-enticing visual charms. Besides the urban-dense streets and hillside stairs of Old Bisbee, it has those looming mountains and a climate cooler than Tucson's. (Elliston clocked the temperature at 92 degrees on a recent day when Tucson hit 111.) The architecture is a wild hodgepodge. The Cochise County Courthouse is an art-deco gem, and St. Patrick's Catholic Church, paid for by an Irish miner back in the teens, is unexpectedly elaborate. Houses can be historic or hippie homemade, and sometimes, the two genres merge. On my visit, I stayed in a rambling upstairs-downstairs house that grew from an old one-room miner's cabin.

It was cheap real estate that reeled in many of the town's pioneering artists. By the early '70s, Bisbee's copper mine was about to go bust, and terrified miners were fleeing for jobs elsewhere. They unloaded their little houses at fire-sale prices, fearful they wouldn't be able to sell later.

Breault and her previous husband, a new professor at Cochise College, bought their first house in town for $300--that's one three and two zeros--a payment for taxes owed. Since then, she's bought and sold multiple houses, many of them tiny wrecks, after living in them and fixing them up. One, she says, cost her $500; she sold it years later for $45,000, "cash." It helps explain why she doesn't feel so pressed to sell her work.

"It's possible for artists to survive," Breault says.

Painter Cadieux also benefited from the real estate bust. The professor plunked down $6,000 for a two-bedroom house "in a nice part of town" that he's had ever since. In the subsequent years, he spent sabbaticals and summers in Bisbee. Five years ago, he took early retirement and settled here permanently.

Once enough artists had settled in town, in their miners' shacks and rundown hotels and bungalows, they created a distinctive small-town arts community. They support each other's work as much as they can--one artist swears that everybody in town owns a crucified-doll piece by local artist Philip Estrada--and they developed arts co-ops and events of a caliber almost unheard of in such a small town. (The population was 8,000 in the 1980s.)

The Bisbee Poetry Festival, just for one, ran some 16 years, from 1979 to 1995, though there were gaps some years. Poets of the likes of Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlighetti and Carolyn Forché came and read their work to the appreciative audience in remote southeast Arizona. The festival, The New York Times once noted, brought in "luminous names from both coasts."

The nonprofit Cochise Fine Arts was a community-run arts and performance space that managed to get competitive National Endowment for the Arts grants. Breault, ever the pioneer, ran a gallery downtown with her husband in a narrow side street, for about 12 years, from 1994 to around 2006. It was called La Chasse Gallerie, Breault says, in honor of a French-Canadian legend Ted's mother used to like to tell. The myth, she explains, was "about fur trappers who got stranded out in the backcountry, and made a pact with the devil to return once a year, on All Souls Night." And when they did, "The women got pregnant."

This fertile bunch evidently lent their creative spirit to the gallery.

"We did poetry there, theater, musical events," says Breault, who's also a poet. "We got grants from the Arizona Commission on the Arts, the Arizona Community Foundation." And the Breaults invited in other artists. "It was also working artists' studio, with a printing press, clay (facilities), a kiln."

The Central School Project is one communal enterprise that still survives. Opened in 1985 in a historic elementary school, it provides studio space to some 14 artist members. Cadieux paints in one of the classrooms; it's a sweeping space still outfitted with blackboards (he uses his as a rack for artwork), wooden floors and huge windows that let in streams of light. But the Central School does more than offer cheap studio space to its artist members. (Cadieux pays $145 a month.)

"We have film, readings, theater and performance art," says founding director Michael Gregory, a poet who just published the collection re:Play.

Last weekend, for instance, the project hosted a border film festival, showing four movies about the U.S.-Mexico border.

The school has a three-pronged mission, Gregory says, not least of which is preserving the old school building, an essential piece of the Bisbee architectural fabric. The other goals are promoting the arts in general in Bisbee and "providing affordable creative space to working artists." But all studio artists have to do a kind of community service: They're board members first and studio-occupiers second.

"A perk of board membership is the ability to rent a studio," Gregory says. "We're not in the studio-rental business."

As of July 1, after 23 years, Gregory was ceding his post as director to a young woman, Melissa Holden. If the best-known Bisbee artists arrived in the '70s, some of the younger ones, including Estrada, are homegrown. And new upstarts have been turning up to carry on the art-rebel tradition.

"I came from the Bay Area 2 1/2 years ago," Holden says, sitting at her new desk in the school office. She's thinking of doing some fine crafts. But whatever she sets her sights on, eclectic Bisbee will spur her on.

With her new arts job, she adds, "I'm getting back into what I came here for."