On a Sunday evening, La Cocina stayed open later than usual. As Tucson band Loveland played songs under the restaurant's twinkling string lights, friends and families chatted, sipped hot cocoa and filled out Christmas cards—not for out-of-town relatives, but individuals currently incarcerated in prisons across Arizona.

The American Friends Service Committee provided greeting cards pre-addressed to prisoners who have reached out to them in the past for resources. They kept a running list of their names so they wouldn't be forgotten during the holiday season.

AFSC was founded in 1917 as the social justice arm of the Quaker faith and has grown into a multinational organization. The Arizona branch opened in 1981 here in Tucson and has focused heavily on criminal justice reform for decades. They view the issue as one of the most significant needs not being met in Arizona or addressed by many nonprofits and organizations.

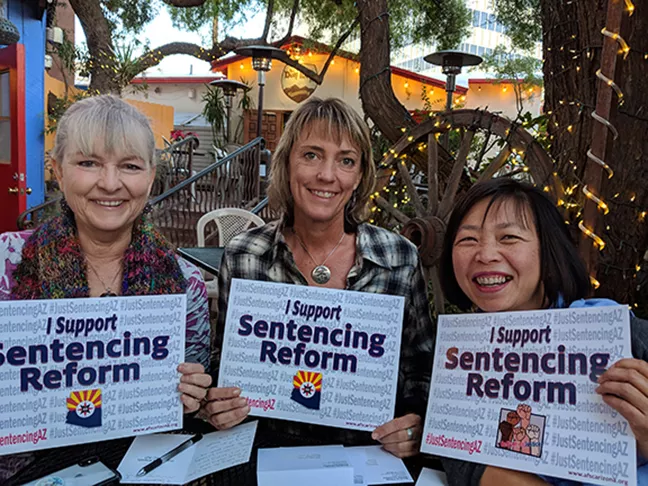

The group organized this holiday card-writing party as an introduction to something bigger. On Jan. 22, AFSC will host ReFraming Justice Day in the Rose Garden of the Capitol in Phoenix as part of a major lobbying effort to enact new legislation regarding criminal justice reform. Free signs declaring "I Support Sentencing Reform" were distributed at each table in La Cocina.

Caroline Isaacs, director of AFSC Arizona, has been with the organization since 1995. She said they've been working on sentencing reform at the state legislature for many years and have made incremental gains. This year, they're raising the stakes.

"If we're going to have to have a fight, let's have a fight worth having," she said.

AFSC is targeting what they believe to be the driving force of the high incarceration rate in Arizona: the requirement that every convicted individual serve 85 percent of their sentence no matter what.

The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 provided federal incentive grants to states with laws requiring violent offenders to serve at least 85 percent of their sentences in prison. Arizona had passed this sentencing law a year earlier, and it is still in effect today.

"In Arizona we applied the 85 percent to everyone," Isaacs said. "So if you go to prison for shoplifting or drug possession, you are going to serve 85 percent of that sentence no matter what you do."

The organization sees this requirement as a disincentive for incarcerated people to participate in rehabilitating programs and services, because changing themselves won't change their sentence.

AFSC will be bringing a group of directly impacted people to the capital for ReFraming Justice Day, where they will give first-hand testimony about how the criminal justice system impacted their lives.

A term used frequently in the AFSC office, "directly impacted person" is an all-encompassing title to include not only current or formerly incarcerated people but also their families, friends and communities.

Dr. Grace Gámez, program director of AFSC, joined the organization three years ago and created the ReFraming Justice project, an initiative that works to change misconceptions about the criminal justice system and help directly impacted people take control of their own story.

"ReFraming Justice Day is set up to be a historic event," she said. "It is the first ever of its kind in Arizona, to have a day that is by and for directly impacted people to talk about legislation and how it plays out in people's lives and to encourage our legislators to adopt fair and proportionate sentencing in Arizona."

Gámez and her colleagues host workshops for people who have experienced the system first-hand, teaching them the necessary skills to do legislative advocacy. She said they talk about how their personal experiences fit into advocating for sentencing reform. They learn how to tell their stories for media while also protecting themselves from reliving trauma or being exploited.

"Frequently our stories are told for us, sensationalized and erase our humanity," Gámez said.

Alexandria Pech, a directly

impacted person and a PhD candidate at UA, was at the holiday party filling out card after card. She has been attending the AFSC workshops in preparation for a testimony she will give during ReFraming Justice Day.

Pech said AFSC was able to teach her about legislative advocacy and government operations in a way that academia couldn't. She learned how to tell her own story effectively, which will hopefully sway the actions of lawmakers.

The legislation they are pushing calls for an end to the 85 percent requirement and instead would allow violent offenders one day off their sentence for every three days served, and for non-violent offenders allow one day off for every one day served. This could allow people with good behavior to reduce their time in prison by about 33 percent.

"This will not only ease the burden on our system and make things fair and more proportionate but we hope that it will actually provide people with some hope and ... give people a chance to earn their way out, the way every system used to be structured," Gámez said.

Upon the early release, prisoners would begin a term of community supervision or probation imposed by the court. However, the prison's director may "deny or delay the prisoner's release to community supervision or probation if the director believes the prisoner may be a sexually violent person," according to a draft of the bill.

If a prisoner fails to adhere to the rulesof the department or fails to "demonstrate a continual willingness to volunteer for or successfully participate in a work, educational, treatment or training program," the director may declare all or a portion of the credits earned by the prisoner forfeited. Those release credits may be later restored.

The director would also be required to provide a detailed account of release credits earned and/or forfeited by each prisoner, which will be presented in a report to the governor, state senators and legislators, and made publicly available.

Isaacs pointed out that this bill doesn't ask to change the way prosecutors are charging or how judges are sentencing. It's just a way of implementing policy that reflects research showing there is a point of "diminishing returns" after a certain amount of time, usually around 10 years.

"We learned a long time ago that actually getting legislation passed, particularly in as polarized a political environment as we have here, you can't just show up every now and then and give a presentation and think you're going to make strides," she said. "So we've invested very heavily in building relationships with legislators and unlikely allies across the spectrum to build trust and change that narrative to educate people beyond whatever kind of soundbites they've absorbed to really understand what's going on."

AFSC reps travel to Phoenix as often as they can to give presentations to legislators, getting them up to speed on what's happening out in the field, catching them in elevators to find out how they're going to vote on certain things and, most importantly, testifying with directly impacted people at committee hearings.

In 2016 the organization had a hand in passing HB2310, HB2307 and HB2010, which relate to alternative sentencing for individuals with mental health diagnoses. That same year, AFSC helped pass a bill expanding eligibility for a program that allows people to be released from prison 90 days early and connects them with helpful services like drug treatment, stable housing and job assistance.

"When a person goes to prison there is utter destabilization, not just in their families but in their communities as well," Gámez said. "I think that the extent to which we can reverse that the better our communities and our families will be."

AFSC has a network of about 50 directly impacted people in the Tucson and Phoenix areas who they reach out to and train in these workshops. While Gámez believes there isn't a true road map for how to do criminal justice advocacy, she said their work is based in science and storytelling. The combination of the two can give insight into these complex systems that most decision makers do not have.

"We serve life sentences in all of these myriad ways," she said. "We experience it in housing instability, in employment, and our children experience that instability as well ... They navigate the system alongside us."

Because of this, the ability to control the way their stories are told is powerful. Gámez said directly impacted people face many exclusions and barriers while simultaneously being expected to be productive, contributing members of society.

"That also provides insight for folks who are crafting policy or interventions to listen to someone who actually went through it, and ask them 'What is it that you actually needed and didn't get?'" she said.

Isaacs said it is astonishing how little data and information there is about the current system and what kinds of impacts it has. "We're blowing a billion dollars a year on this thing and nobody's paying attention," she said.

There is a common belief that if someone is in prison, it's because they belong there. But Isaacs said punishing the behavior out of people doesn't work, and at a certain point, it becomes retribution.

"The spoken or unspoken belief underlying a lot of our policy that people commit crime because they are inherently bad people ... has got to be addressed," she said. "If we actually believe that people can change, we wouldn't do that."

AFSC has conducted original research on Arizona's use of solitary confinement, privatization of prisons, drug sentencing and other important topics.

"That helps us build credibility with people who want to dismiss us out-of-hand as liberal or biased or what have you," Isaacs said. "If we can say 'We know something that you don't, you have to talk to us,' that is a helpful thing and that's worked very well."

Her best strategy for getting things done is to never assume any person or organization is not a potential ally.

"We all want safer communities," she said. "The problem is that their definition of what that is and how you get there is different than mine."

AFSC has created a "left-right coalition" made of groups across the political spectrum who have interests in criminal justice issues. This includes the ACLU, Americans for Prosperity, Right on Crime, and various defense attorneys, domestic violence advocates and lobbyists.

While they obviously don't agree on everything and it makes for some difficult conversations, Isaacs said working across party lines is the best strategy to reversing some of the harmful stereotypes that dominate the conversations about justice.

"The entire system is built on misconceptions," she said. "I'm not exaggerating... It is a politically convenient myth that this system functions to keep people safe. It certainly doesn't, but I would say that it really isn't designed to, it's designed to keep certain people safe."

"One of the most frustrating things that I've had to fight against as a directly impacted person is that I am valuable," Gámez said. "That I am not a throwaway, that you don't need to banish me, because I have things to contribute."