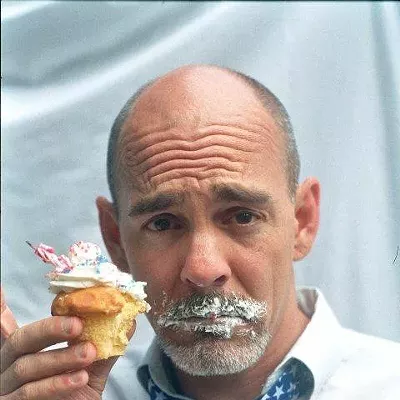

Legendary British musician John McLaughlin is revered by many as one of the speediest, most inventive and most fluid players in jazz, fusion or world music. Though his chosen instrument may be guitar, McLaughlin's two primary inspirational heroes were horn players: trumpeter Miles Davis and tenor saxophonist John Coltrane.

It's only coincidence that McLaughlin plays the guitar, really. In a recent (and rare) telephone interview, he said he doesn't subscribe to the school of guitar fetishists; he simply considers the guitar one of many tools for reaching a higher level of expression.

"I always wanted to play like Miles and Coltrane. They were the ones. In my head, I could hear my guitar playing like they played."

Backed by his band, the 4th Dimension, McLaughlin will play Friday, Dec. 3, at the Fox Tucson Theatre.

McLaughlin's list of collaborators over the years reads like a who's-who of not only jazz, but rock and world music: Tony Williams, Carlos Santana, Chick Corea, Paco de Lucia, Al Di Meola, Joey DeFrancesco, Kenny Garrett, Christian McBride, Elvin Jones and Zakir Hussain. But he always returns to the music of those two titans.

McLaughlin was fortunate as a young man to be recruited into Davis' band during the late 1960s and played on such stellar, proto-fusion albums as In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew and A Tribute to Jack Johnson. Although he never had the opportunity to play with Coltrane, McLaughlin was incredibly moved by the tenor-man's work, especially the landmark 1965 album A Love Supreme.

Now, the 68-year-old McLaughlin has created a tribute to A Love Supreme with his latest album, To the One, which was released earlier this year.

The tunes on To the One are all McLaughlin originals and played on guitar (sometimes guitar synthesizer) with the 4th Dimension, a primarily electric group. But the spirit and spirituality of Coltrane's classic album inspired the recording through and through, especially in the way McLaughlin's playing balances beautiful melodies with cascading rushes of soloing that call to mind Coltrane's trademark "sheets of sound" style.

McLaughlin is playing some of that material on his current tour with the 4th Dimension, which includes Gary Husband on keyboards, Etienne M'Bappe on electric bass and Mark Mondesir on drums.

Of A Love Supreme, McLaughlin said, "I guess it is one of those delayed reactions, 45 years later. I heard that album when it came out in '65, and was immediately taken with it. It's not a collection of compositions, but one huge musical statement that will influence listeners for generations.

"I had heard him play with Miles in the 1950s, and his own stuff in the early '60s, and that was amazing, but this recording took a great command over me, and I knew from there what I wanted to do with my life, and life would be a pursuance of not only music, but spirituality. And it has proven to be."

One of the most important lessons McLaughlin learned from Coltrane and A Love Supreme is the concept of gratitude, he said.

"Gratitude is the most healthy attitude and state of mind to live in—just being thankful for what we have and our place in the world and beyond. Considering how confusing our modern society is, if you have this sense of gratitude, you will find peace, and you will be happy."

A few years after hearing A Love Supreme, McLaughlin joined drummer Tony Williams' band, Lifetime, and soon after was playing with Davis.

"Like I said, I had heard Miles in the '50s, and Milestones was very important to me, because I had heard Charlie Parker and bebop, and that didn't do it for me. Miles took that in a new direction. By the time I had found my way to him, he wanted to have guitar in the band, and it was the beginning of the fusion thing, working rock influences into the jazz sound, and a lot of people hated it. But for me, it was very freeing."

The music of Miles Davis brought McLaughlin's love of jazz together with his early-1960s playing in R&B, blues and swing bands with such artists as Georgie Fame, Graham Bond, Brian Auger and Ginger Baker.

But Davis wanted something different from the young McLaughlin, who likened Davis' playing and attitude to a Zen koan. At first, McLaughlin had a hard time fitting his style to it.

"When we set about recording early on, I was trying all this different stuff, and it wasn't working. So Miles came up to me between takes and said, 'Just play it like you don't know how to play the guitar.' I did, and then I looked up, and the red light was on. He'd been recording it."

After leaving Davis' group, McLaughlin formed the Mahavishnu Orchestra, which used his growing interest in Eastern spirituality as a foundation for taking fusion further into the 1970s. Later, he founded Shakti, in which he more openly explored the connections between acoustic jazz and Indian music.

McLaughlin said that in naming his new group, he was partly inspired by the concepts of time and of another hypothetical spatial dimension. But the name also refers to music.

"For me, music is a dimension. Without time and space, music will never exist. Music is a function of the fourth dimension. It's lovely for me that we can live in this dimension and then experience the fourth dimension through music—you know what I mean? Scientists might have a hard time explaining the fourth dimension to laypeople, but I don't. I just tell them the fourth dimension is music."

For 2011, McLaughlin is preparing for another tour by Shakti, with percussionist Zakir Hussain. He and Santana are also in talks about reuniting for some music festivals next year.