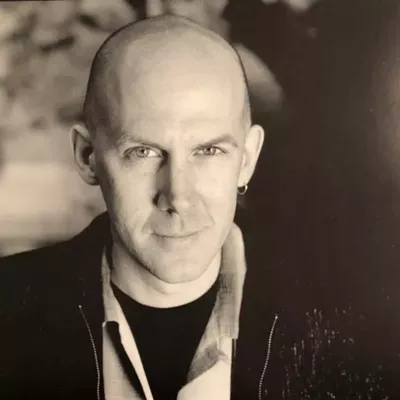

"In other parts of my life," says Billy Sedlmayr, "I couldn't have done any of this. It takes too much discipline."

On a late afternoon in the barely waning summer, Sedlmayr talks about the long road making his solo album "Charmed Life," 12 songs (stories, really) written from the other side of his greatest struggles, sung in a world-weary voice that perfectly complements his words.

After years of drug-addiction and a decade behind bars, Sedlmayr found his calling as a writer, combining lessons learned in prison workshops with a heavy dose of perspective from the experience and, at long last, the focus necessary to actually get shit done.

Sedlmayr, a founding figure in Tucson's punk scene who later played in Giant Sandworms, returned to music with something to prove, wanting to match all of the old bandmates and peers who'd long ago surpassed him.

"The music, I felt like it was undone. It felt like I'd never accomplish anything that my homeboys had accomplished. The guys I grew up with and came up with, in every band, most guys went on to do something," he says. "I never finished anything I started. I got kicked out, or I screwed it up. I let a lot of things go."

With Elton John playing softly in his Midtown apartment, Sedlmayr talks about his time with the Giant Sandworms in New York, with him, Howe Gelb and Dave Seger (Sedlmayr's old bandmate in The Pedestrians) sharing an one-room apartment.

"At that point, we really hoped. I know we were a schizophrenic sort of band, but we had some good stuff. Every band I've been in I enjoyed," he says.

But too often, Sedlmayr himself was the one who broke up the band.

"That got so old after I'd lived it. You miss out on a lot of things that you wanted, that you dreamt of," says Sedlmayr, 53. "No matter what happens with this record, inside a piece of me will be really, really happy that people believed in me."

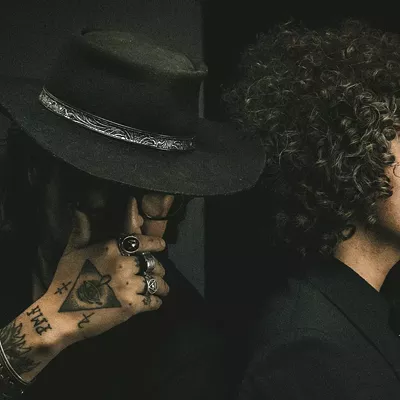

Recording an album began to change from a one-day-maybe dream into a tantalizingly real possibility when Sedlmayr met Gabriel Sullivan, a musician barely half his age.

In 2009, Sullivan was booking music and regularly playing at the Red Room. He signed Sedlmayr up for a weekly songwriters' showcase and the first impression was a strong one.

"Right away from the first show, he asked me to sit in and after that I knew that this guy really had something," Sullivan says. "I didn't have a clear vision of what it would be, but I knew I wanted to help this guy document his music."

Sullivan worked out a full-band arrangement for one of Sedlmayr's songs, "Tucson Kills," and produced a live performance video. Potentially a test run for a series of videos that didn't come to fruition, the clip ultimately formed the backbone of a Kickstarter campaign. It went down to the final hour, but Sedlmayr and Sullivan reached their goal of raising $10,000 to record and manufacture a full-length album.

"In the beginning, I didn't think of putting out a solo record per se. That seemed pretty far out there, like a lighthouse in the distance or something," Sedlmayr says. "When Gabe mentioned it to me, I got interested, I still didn't believe it was going to happen. When the Kickstarter happened, I sat there in shock for a night. Be careful what you wish for. We had to put out and I felt apprehensive."

Aside from the obviously autobiographical "Tucson Kills," the songs aren't particularly personal, but reflect Sedlmayr's world-weary view on his surroundings, stories he's seen or heard along the way.

"When I wrote that, I knew I couldn't say that it wasn't me. Usually, I write out of a desperation of some sort, good or bad, a need to get something out, to say something," he says. "But every song isn't a confessional. It's not that heavy. It's stuff I've seen or watched."

Sedlmayr's dedication to writing came from working with Richard Shelton, the renowned poet and essayist who first established a writing workshop at the Arizona State Prison in 1974.

"It was incredible," Sedlmayr says. "Dick was super kind to me. Watching him work and reading his work was a huge influence. To have that kind of commitment... and he never got a penny. Only heartbreak."

Writing became Sedlmayr's way of dealing with not only the time in prison, but his past, and he was published in five issues of the Rain Shadow Review.

"Some cats get zen in there, but I didn't find it to be a place of zen. It's a lot of trouble and a lot of bad shit," he says. "I never thought that I shouldn't have been punished. I never felt that way. There's a place you have to learn in yourself. Punish yourself and then rise above it."

Still, after his release from prison in 1995, Sedlmayr found himself back in prison on a drug charge in 1997. At first, he felt comfortable being back inside.

"There's something wrong with that, something sick," Sedlmayr says. "That's not where I'm at anymore."

Sedlmayr still keeps up with a weekly writing workshop at the University of Arizona's poetry center. He's writing short stories and prose poems and working to finish his novel. "It's easier for me to do than writing a song. They come slow," he says.

"Billy clearly has a circle of people supporting his writing and his novel and I have no doubt that will come to fruition," Sullivan says. "But he had flames with a lot of different musicians in town flickering out by the time I met him. When I started to play with Billy, he was really on his own. We'd play in the living room and that was the only time he got to jam with anybody."