Back in 2008, the Tucson immigrant-rights group No More Deaths accused the U.S. Border Patrol of systematically abusing detainees. Those allegations were contained in a searing report that prompted a few headlines, a smattering of Border Patrol denials, and then silence.

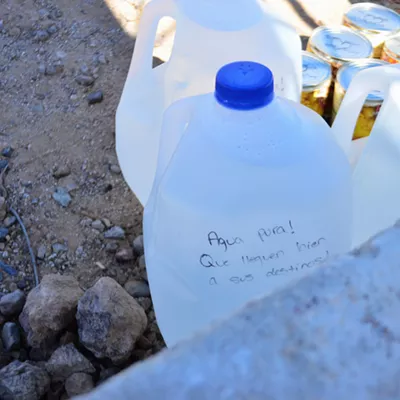

Three years later, the same group has issued another, far-more-expansive report. Compiled from interviews with nearly 13,000 recently released migrants, it paints a grim picture of Border Patrol detention. The migrants describe dehydrated people being held without water, sick people being denied treatment, people needlessly being crammed into cells, and others being beaten while in custody.

Skeptics, of course, will label such accounts mere fabrications, impossible to verify and lodged by folks with a political ax to grind. But for the sake of argument, let's say that just a fraction of these troubling accounts are true. If so, has the Border Patrol, or its parent agency, the Department of Homeland Security, investigated a single one?

I posed that question to Victor Brabble, chief spokesman for the Southwest Border Joint Information Center. That's the local PR office for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, a division of the Department of Homeland Security division which includes the Border Patrol. What I received was this written statement:

"As a matter of policy," it said, "Border Patrol agents are required to treat all those they encounter with respect and dignity. ... Mistreatment or agent misconduct will not be tolerated in any way. Any agent within our ranks that does not adhere to the highest standards of conduct will be identified, and appropriate disciplinary action will be taken.

"We appreciate the efforts of individuals," the statement continued, "to report concerns as soon as they arise, and we will continue to cooperate fully with any effort to investigate allegations of agent misconduct or mistreatment of individuals."

That sure sounded promising, at least on paper. So I decided to find out just how many such investigations of detainee abuse have occurred, and the type of disciplinary actions imposed.

Brabble wasn't able to offer much information beyond the statement. Instead, he referred me to the DHS Office of the Inspector General.

According to its website, the OIG serves as "an independent and objective inspection, audit and investigative body to promote effectiveness, efficiency and economy in the Department of Homeland Security's programs and operations, and to prevent and detect fraud, abuse, mismanagement and waste in such programs and operations."

So I contacted those independent offices, hoping to discover a roster of tough actions against abusive agents. Instead, I was stonewalled. "Unfortunately, we cannot comment on any ongoing investigations or give you any direct information," said DHS spokeswoman Rachael Norris in Washington, D.C. "But what I can do is provide you with a couple of reports we've completed."

Norris subsequently sent me beautifully compiled reports, complete with flashy graphics, which had absolutely nothing to do with detainee-abuse allegations. When I pointed this out to her a day later, she dug a bit more, and followed up with a link to a congressional report prepared by DHS—which also said nothing about detainee-abuse issues.

"Let me assure you," Norris wrote in the accompanying email, "that we are dedicated to the fair and just treatment of all individuals placed into our custody. Any DHS employee involved in any such activity will be investigated with the full resources of this office and, where appropriate, prosecuted to the full extent of federal law."

After three days of this circus, I took one final—and ultimately futile—stab at getting actual evidence to back these repeated assurances. At that point, Norris turned snippy. "I've provided you with all the information I can at this time," Norris said on the phone. "If you're seeking additional information, you can file a (Freedom of Information Act) request."

Federal FOIA requests are notorious for interminable processing, and heavy redaction that often renders them meaningless.

Back in Tucson, such DHS shell games hardly surprise No More Deaths spokesman Adam Aguirre. Regardless, he says the testimonies compiled by his group speak for themselves. "Across at least three different sites where we were interviewing recently detained people, and across 3 1/2 years, we saw amazing consistency in the types of abuse that were being described.

"To us, that spoke very loudly that this wasn't the issue of a few rogue agents, but that this was, in fact, a systemic issue—that there was a system of abuse going on, not just along the border, but all over the country in Border Patrol short-term detention facilities."

Over that time period, "we helped to file 75 formal complaints," he says. "And over that 3 1/2 years, we saw zero identifiable outcomes from the complaint. What that tells us is there's no transparency and no accountability."

All of which sounds quite familiar to Ephraim Cruz. He was a nine-year Border Patrol veteran at the Tucson Sector's Douglas Station when he was forced out after complaining of detainee abuse. In memos to his supervisors, Cruz described detainees being deprived of food or water, and needlessly being shoved into overcrowded cells. He claimed that minors were commonly released to complete strangers.

For his trouble, Cruz saw his routinely shining evaluations suddenly turn critical. He was ostracized, placed on humiliating library duty, and ultimately indicted on trumped-up charges of transporting an undocumented woman across the border.

In March 2007, a federal jury acquitted Cruz of all charges. But eight months later, he was forced to resign or face termination.

Now living on the East Coast, he says his fate was clearly a warning to other potential Border Patrol whistleblowers. "I won the battle over (questioning) my credibility on the abuse reports," he says, "but I lost the war. Now, for other agents to do what I did would be like stepping into the abyss."

Today, he has no doubt that abusive practices—such as those highlighted by the No More Deaths report—persist within the Border Patrol. Indeed, he considers it embedded in the agency's culture.

"It's a repetitive cycle," he says. "If we look at some of the folks who I was reporting for wrong-doing, these guys have since received promotions. Their actions have been rewarded."