I am hunting for hints of the soul of a dead man. The stacks of plastic boxes filled of his personal belongings smell of dirty pennies and mice, his losses and wins often reduced to itemized statements and news clippings. The dead person and his things mingle with a sudden heightened awareness of life. It is as close to a ghost as you can get without understating any of his true demons and indignities. Leaves one with an unsettled feeling.

He lived a fascinating life as aimless as it was direct, as certain as it was uncertain, and seemingly dispensable. But nothing about him feels dispensable, these scraps, fragments and implied memories show a man in a forever search of something tangible, and he created tangibles.

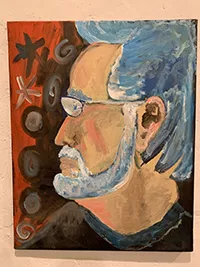

I had never joked or argued with Charlie Spillar, never even met the man, but I harbored an infatuation with his art, these mad folk-pop paintings and sculptures whose cartoonish twists of absurd illusions saved them from the land of kitsch. I wanted to know more about this man whose seeming Peter Pan heart had failed him. Those who knew him share rousing stories, how his mind was crammed of ideas, how he wasn't so concerned for the day-to-day, more beholden to whatever narratives and chirrups he heard in his head, many of which never got out. They say he was a complexly wired dude, a different person to different people, would only reveal aspects of his personality he thought would fit whatever scene.

He died a pauper, lived on waning art sales and whatever Social Security stipend, though his forays into the industrial complex saw him make a damn good living at times, years ago, but he said fuck you to all that.

Spillar had a fine two-bedroom apartment that in recent years—in his failing health—became a kind of hoarder's wonderland, near the University in the Dunbar-Springs neighborhood where he lived the last 12 years of his life, and paid $550 a month. Its walls were filled mostly with his own paintings. I describe him as a loner but his close friend and volunteer-work cohort Bo Popovic, a highly educated woman whose specialty is art, corrects me, saying he was solitary, yes, but not a loner. He had friends, a few close ones, some enemies and burned bridges, and many acquaintances from all parts of the world. His art earned him a cult-following of crusty oddballs, tin-foil heads, art collectors, fans and academics. He didn't suffer fools. He was polite, didn't get drunk and piss in corners, was straight-up and honest.

He had no children, had girlfriends and lovers along the way but never married. He died alone in his bed in October last year, discovered days later. One way to go, alright. Maybe how he wanted it. He was stubborn, eschewed Western medicine in favor of holistic approaches, used prickly pear juice to treat his diabetes, for example. His heart problems went undiagnosed until he suffered his first heart attack last spring.

Beyond the context of boxed dead-guy sadnesses, things in these piles reveal an abstract air of responsibility about him, like how he kept up with his taxes, how he treated his own art, and the art and welfare of others, with care and respect. And how he brought people together in ways that shifted the landscape of this city.

Spillar championed nonprofits Valley of the Moon and Healing Arizona Veterans. He mastered wily get-cash schemes. For example, it was likely his tears that got the huge grant from Scripps Media in late 2018 to benefit HAV, a donation-based organization that sponsors treatment of military vets suffering from TPI and PTSD using a well-documented procedure called Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy. "He cried during the proposal with Scripps," Popovic says, laughing. "I've never seen this man cry. And that probably sealed the deal. He could really sell. He wasn't a vet but he was so connected to many who were."

Southern Arizona folk might remember Spillar's romantic crusade to resurrect the Cactus Drive-In Theater. Spillar worked hard only to see the project languish. He was proud of the work and saved newspaper clippings to prove it. He rescued many of the psychedelic, H.R. Pufnstuf-looking creatures and castles from long-gone Magic Carpet Golf, created by the late roadside attraction artist Lee Koplin. (Some contend the pieces were actually made by brothers Michael and Andy Kautza.) The bigger-than-life, rebar-and-concrete creations include the streetlight-tall Tiki Head. This red-eyed Instagram cliché decorates the entrance to the Hut bar on Fourth Avenue. Other pieces found homes in Tucson, and four rest here at Valley of the Moon in Tucson, where I am now, on the floor sifting through his life.

If not for Spillar, those goofy-golf works, all indelible to brainpans of folks who grew up in Tucson, would've piled onto landfill heaps. If not for a few caring friends of Spillar, his art and things would've decorated a trash heap too. Perhaps the same with Valley of the Moon. Always one step from the trash heap. Dispensable? Hell, no. His friends knew that about Spillar, spent arduous hours going through his apartment, securing his art and personal belongings. Rescuing Spillar's domain was a months-long task, fraught with city red-tape and rental-company protocols involving eviction laws. The property owner and the property manager's attorney were pretty heartless in their attitude toward Spillar's memory.

Spillar's pal Sa'ad J. Allawi, the operations officer at HAV, hired a lawyer to wade through the morass. After filings and affidavits, which involved tracking down Spillar's one elderly sister and brother-in-law in Louisiana for permission and a notarization, they gained access and ownership of Spillar's world. That world is being sifted through still. Jenni Sunshine, the droll, articulate president of Valley of the Moon, will send sentimental items back to Spillar's few relatives in Louisiana.

"There is a feeling of putting things right in liberating Charlie's infectiously happy art from his dark, disorderly home," Sunshine says. "It's as if all the depressing stuff has fallen away, freeing goofy birds and pictures of connection and fun. It seems to me exactly how a life should progress to nothingness after death under the best of circumstances."

Today Spillar's rescued art is beginning to get hung by Sunshine and an electrician they call Sparky for an upcoming gallery show in the adobe house on the grounds of the lovely Valley of the Moon. (The net proceeds from Spillar's art sales will be split between HAV and Valley of the Moon as charitable contributions.) The beautifully rehabbed adobe structure serves as a nervous system for the park: an office, a gallery space, several rooms and storage.

It is easy to see why Spillar was drawn to Valley of the Moon after arriving in Tucson in 2004. In ways it reflects him.

It feels almost holy here. Smells are sharper, colors richer, insect sounds more conspicuous, the constant hum of silence only occasionally interrupted by far-off city noises. With its ghosts, outlandish creations, and articulated kid-whimsy, which include churlish gnomes, eerie passageways, an outdoor theater, stone and metal art, lighted gardens, and those Magic Carpet Golf creations and flowers. A family of colorful doorways feels like an entrance to alternate realities. The place is pure lo-fi but closer inspection rewards—it is unpredictable and subversive, gives an illusion of liberation from the external world gone haywire. It is wholly open to interpretation, and kind of dada because it can subtly challenge a reexamination of our accepted values. No shit.

The park is an area heart-spark, conceived back in the jazz age when Tucson was a dusty blip surrounded by rivers, farmland and cholla-mesquite forests. Postal clerk-artist-spiritualist George Phar Legler created the now-historic fantasyland as a place of "kindness and imagination."

The three-acre ground overcame near-ruin and myriad obstacles over the years to retain its troubled independence in order to promote tolerance and love, guided by seasonal events and theatrical fundraisers. Spillar worked Valley of the Moon hard, having once done time as its spokesman and publicity director.

One box contains neatly arranged folders. One, labeled "The Happy World of Charles Spillar," contains typed-out step-by step instructions on how to create one of his ceramic sculptures, and I'm not sure the folder isn't meant as a joke. Another contains a cache of hundreds of yellowed, hand-written letters from his father, rubber-banded stacks postmarked Louisiana '70s and '80s, whose words show a deep affection toward his son while documenting the tender mundanities of an ageing dad's daily life, like how a latest gumbo-from-scratch concoction did him proud. The communications sometimes contain newspaper clippings of someone Spillar knew in another lifetime.

That lifetime began in the Louisiana bayou where Spillar was born in 1942. Where he was selling shoes at 13 and saw his first art exhibition in 7th grade; charcoal paintings of nudes drawn from his old man's Playboy collection. The work caused a ruckus, nearly got him ejected from school. The kid was so discouraged he hung up his art for years.

"It has been a long winding, often hilly trail to reach my artist career," he wrote.

Spillar chose the Army National Guard after high school, and worked for G-2 Intelligence. To pay for studies at the University of Oklahoma, he worked as a crawfisherman, an oil-field roughneck, highway construction worker, a Fuller Brush salesman and so on. He graduated with a degree in economics and finance.

He became a buyer at IBM in Colorado, later a licensed securities agent (helping raise millions for a commuter airliner), a director and VP of a NASD securities company. His search for autonomy found him ditching the tedious corporate complex multiple times to travel Europe. Stock market stress sent him reeling, he wound up in San Francisco and Denver working in finances and a fortune 500 company, and traveled throughout America. He'd pause and ask: at what price? Soulessness? He began to paint again.

Spillar's beating heart won over commerce. He lived in the Greek isles and painted. He settled in Seattle to work, found survival gigs in industrial textiles and medical supplies. A few years later he was living on the Mendocino Coast working art fulltime, and represented art galleries in several states. I find colorful postcards from various shows in California featuring his work. He had a studio, created hundreds of pieces and sold them through his gallery and collector connections. He penned freelance pieces about culture and art for local newspapers. Art can barely support anyone, it's for rich folks to collect because the kids can't afford it. When the economy tanks, the rich don't spend. He put in one hell of an effort to survive on the art, sometimes relying on the grace of friends.

Spillar was keen on showbiz, and at one point he embraced Hollywood, where he studied screenwriting and worked on his art. One box containing piles of call sheets shows his employment on films and TV—from the Warren Beatty-helmed Dick Tracy to the Dark Shadows reboot in 1990. He penned TV and movie scripts, even optioned one, a TV mini-series that was never produced. He struggled and worked odd jobs in L.A. One got his pic on the cover of the Advertising Age magazine—selling ice-cream sandwiches from a push cart. During a film-TV writer's strike he worked on a fish vessel in Alaska. He hitchhiked through eastern Alaska and the Yukon, opening a food brokerage in San Francisco before returning to Hollywood. He worked fulltime as a lighting tech, 12 years in Hollywood on more than 100 TV and feature films.

One box contains framed certificates including his 1983 completion of hypnosis and study from a hypnotism training institute in Los Angeles. He was a licensed hypnotherapist. There is one from the mayor of Tucson.

I find magazine profiles from those he respected, avant-garde artist Beatrice Wood and Niki de Saint Phalle, a feminist sculptor from whom Spillar drew inspiration—these joyful, even cartoonish forms with a deceptively childish bent, a lurking menace below the surface.

He chose Tucson mainly for its community of artists, no matter how insular. He claimed he had sold 3,300 pieces of his art. He penned a weekly column-blog on Tucson Citizen website, writing about art, galleries and such. He did some substitute teaching. He found Valley of the Moon.

Though I missed the Spillar service in November, I accompanied Popovic and Sunshine one day to the funeral home to collect Spillar's ashes and deliver them to Valley of the Moon. It wasn't sad, it was almost funny. Sunshine, Popovic and others loved Spillar unconditionally, respected him tremendously, find the humor in his life, how he is more alive now than a lot of people who actually are alive. It is why they keep his legacy afloat, the way Spillar did with his father's letters and those oddball creations from Magic Carpet Golf.

Why Spillar saved the things he did tells of a guy whose logic (and truth) was internal, a person with a potent inner-life, which fueled his work, and, at the risk of dead-guy reverence, fueled him to help others. His life in these boxes showed one lengthy account of a hunt for personal freedom, vindicated in his autodidactic art. A hint at the soul of Spillar.

"Being totally self-taught has proven to be an asset to me," he once wrote.

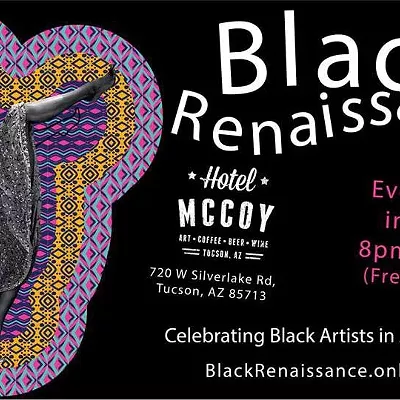

The Charlie Spillar art gallery retrospective (The Wacko World of Charlie Spillar) happens from 7 to 8:30 p.m. on Thursday, March 19, at Valley of the Moon, 2544 E. Allen Road; 520-323-1331. It's free, all ages. The retropective will be ongoing but sporadic, email wizard@tucsonvalleyofthemoon.com for more info.

Brian Smith's collection of essays and stories, Tucson Salvage: Tales and Recollections of La Frontera, based on this column, is available now on Eyewear Press UK. Buy the collection in Tucson at Antigone Books, 411 N. Fourth Ave.