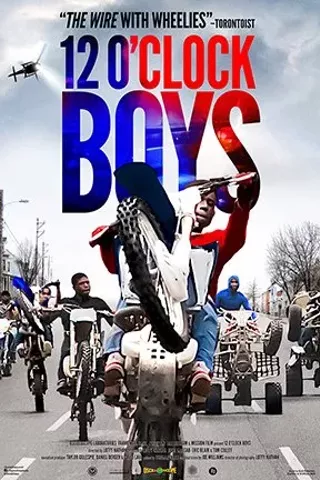

In inner-city Baltimore, it's a tradition and rite of passage for African-American men to ride dirt bikes through the streets. It's illegal, and that's at least part of the point. The police are forbidden from pursuing the riders because, when there are dozens of bikes going every which direction, it's simply too dangerous. So the cops have to track the dirt bikes with helicopters, catching only a few, and the attention hooks kids such as Pug.

The documentary 12 O'Clock Boys traces the culture but not much of the history, focusing more heavily on Pug and his family. We meet him at age 13, in 2010. Within a year or so, he's got gold grillz, a few arm tattoos, and finally his own bike. Says one of the veteran riders, "The thing about Pug, he's a real cool dude. Little dude; I think he's gonna grow up to be something."

The question, as a viewer, is whether Pug will grow up at all. A former Baltimore P.D. officer and independent security contractor says street racing kills about 15 people a year, a high number when fewer than 100 people participate. Most of the fatalities are riders, but some are bystanders. And the more the cops try to take it away, the more the community grows.

The title of the film refers to the original gang of dirt bike riders, who invaded the streets not to maraud or cause trouble so much as to have something of their own. It's impossible for a movie—especially one that only runs an hour and 15 minutes—to capture all the angles, but it doesn't seem that the culture surrounding the dirt bike racing has evolved at all. It's still presented as just a thing to do, as something the police better not try to take away.

Director Lofty Nathan gets remarkable access to Pug and his family, practically living in their house. Of course, Pug's mother, Coco, jokes about getting her own reality show someday, so maybe she was just intoxicated by the presence of the camera. There is something about Pug, prematurely hardened and preternaturally charismatic, but by 15, he's already shouting the local battle cry ("Fuck the police!") and talking openly about stealing his bike back. Speaking to the access Nathan gets in the film, we actually see Pug's bike get stolen in the first place, and watch some guy ride off with it right in front of him.

The societal critique is easy to make, and probably just as easy for a conservative crowd to conflate to nanny state proportions. It appears evident that Coco receives a fair amount of government assistance, but amid all this poverty is a parade of brand names. Pug wears Polo clothes almost exclusively and so do all his friends. His mother is decked out in Ed Hardy from head to toe. And yet, they live in one of the worst and most violent urban areas in America. Pug has all but given up on school. It's never spoken about but it doesn't appear Coco has a job. She also has other kids to worry about. You can't help but wonder if things would be different had Coco reprioritized things in their lives. It wouldn't change anything about the movie, of course, because if it wasn't Pug it would be another kid.

From a filmmaking standpoint, though, the problem is that 12 O'Clock Boys never closes any loop or takes any position. It's all prologue. While it's an eye-opening and at times shocking picture that Nathan paints, it's an unfinished portrait. Is this a perpetual cycle? Are there kids like Pug who have found a way out of this life? How does the rest of Baltimore feel about it? 12 O'Clock Boys apparently has no idea, or any interest in finding out.