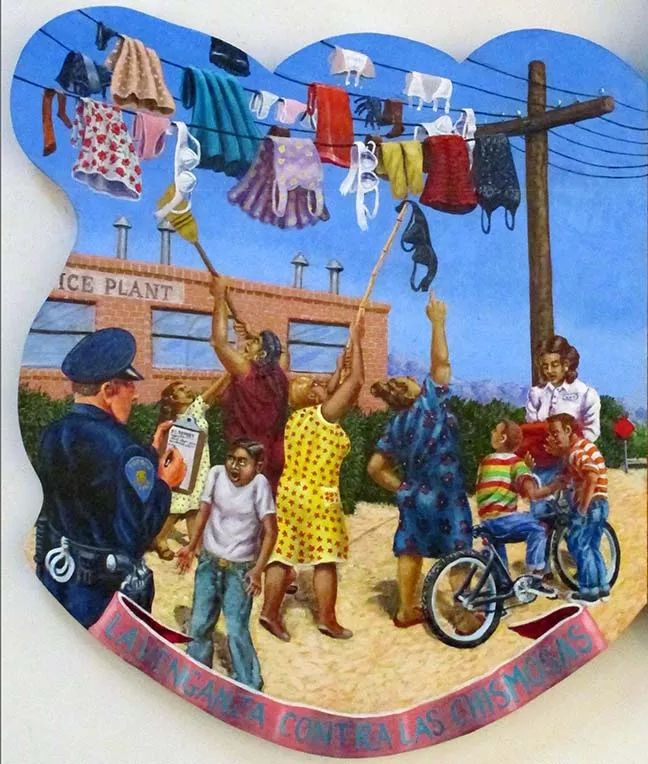

One day long ago, in the Millville barrio of Tucson, a woman's entire wardrobe dangled from the telephone wires high above the street.

Dresses, bras, girdles: some miscreant had tossed them up there for all to see.

The owner of the clothes was Alfred Quiroz's mother, but young Alfred told a cop that he had nothing to do with this humiliating prank. He looked scared as he talked to the investigating police officer, a white man in a Mexican-American neighborhood.

Meanwhile, the mujeres of the barrio attacked the wires with brooms and poles, struggling to unmoor the clothes and put an end to their neighbor's embarrassment.

Quiroz has memorialized this episode from his childhood in a beautifully painted triptych now hanging at Davis Dominguez Gallery in Alternate View, a double show featuring the retired UA prof's paintings, drawing and prints, as well as printmaker Kathryn Polk's lithographs.

The rollicking painting, "Las Dilemas del Barrio, Millville, 1954," is a large acrylic on board that's been energetically shaped and cut around the edges. The clothes' mysterious appearance outdoors (gallerist Mike Dominguez reveals that Quiroz's best pal, Tommy, was the culprit) is just one of three catastrophes memorialized in the three-part painting.

In the dilema on the right side of the work, a firefighter has arrived to retrieve a smoking pot of burnt beans from an adobe house. The guardian angels of the neighborhood, the hard-working women in calico dresses and aprons, once again are on the scene, this time to lament the disaster.

In the center section, naughty Tommy is airborne, blown off his feet by an invading dust devil. Alfred and another boy are horrified as they watch their buddy fly pell-mell into still another telephone pole, slamming his head, hard, against the wood.

These 64-year-old tragedies, large and small, real or exaggerated, are here given heroic resonance. Quiroz is best known for painting stinging political satires, but several paintings in this show reflect a tenderness about his own past.

Another view of Millville is more subdued. While "Las Dilemas" features Quiroz's trademark zinging colors and wild, cartoonlike humans, "The Universe in God's Calf, Barrio Millville" is a graphite drawing in muted black, white and gray. It's as realistic as Quiroz gets, picturing small houses lining dusty lanes, trees and fields that look almost rural.

A giant human leg—a lot like a milagro in a shrine—floats over this humble place, emblazoned with a text that declares Millville was "so minute that it existed in God's calf."

Millville still exists near downtown, though somewhat gentrified. It's east of the renovated Ice House Lofts (which make an appearance in the laundry panel as a working building labeled "Ice Plant"), and south of the railroad, north of 22nd Street and west of Kino.

It's tempting to think of that old barrio as Quiroz's ur- inspiration. Certainly it shaped an aesthetic steeped in Mexican folk art, with its rich colors and written slogans, and his pride in those powerful mujeres. But Millville's poverty and low status—why were the streets unpaved well into the 1950s? Why were the cops and firefighters all white?—may also be the wellspring of his dogged political art.

I'm reminded of a searing multi-media piece Quiroz made in the 1990s, about the death of young Chicano soldier in the Korean War. "Alla en el Rancho Grande," not in this show, had a painted triptych that began with a proud mother beaming while her musician son sang to her and ended with an officer presenting a flag to the dead soldier's weeping parents.

An actual coffin stood in front of the painting. Perhaps Quiroz—himself a Vietnam vet—saw the a real young man's remains being carried in Millville long ago, and that memory fueled the artist's rage against a world where the poor fight and die in rich men's wars.

The Davis Dominguez show does have plenty of classic Quiroz political works. But this time around, instead of deconstructing history in canvases that tell the ugly truth about cherished American myths, Quiroz uses art history as a frame for mischievous paintings that skewer a certain American leader and all his works.

Mr. Trump appears nearly nude in a big painting that mocks the "golden showers" he allegedly enjoyed pre-presidency from Russian prostitutes. "Don-Nay and the Shower of Golden Rain," an oil on canvas, is based on three 1560s paintings by Titian titled "Danae Receiving the Golden Rain," about a princess in Greek mythology.

The original works picture a languid Danae stretched naked on a bed; the golden rain headed her way is actually Zeus in liquid form, rushing to impregnate her. The Trump version has the pink-fleshed president in a similar pose, ready to receive the fluid. An extra added attraction is presidential pal Putin metamorphosed into a cherub floating overhead.

Elsewhere, Trump transforms himself, myth-like, into a ridiculous Donald Duck. The painting "Leda and Donald" is a take-off on the myth of Leda, whom the busy Zeus either raped or seduced while in the form of a swan. Artists from ancient Greeks to Da Vinci and Cezanne have painted versions of this story, but Quiroz converts the swan into the Disney character. Come to think of it, Donald Duck, quick to anger and verbally incoherent and chaotic, is a lot like you-know-who.

Quiroz seems to cheerfully skewer himself in "The Great Chicano Artist," based on "The Painter's Studio," an allegory painting by Gustave Courbet from 1855. The artist in question sits at his easel, painting still another Virgin of Guadalupe, while in his crowded studio adoring fans, a critic and a TV crew admire every stroke he makes. The walls are filled with clichéd paintings of bleeding hearts, Frida Kahlo portraits and Aztec gods. The piece takes a good-natured stab at stereotypes, and the risk that ethnic art can paint artists into all-too-confining box.

Across the gallery is a suite of poetic stone lithographs by talented printmaker Polk. Beautifully crafted, each of the delicately colored works pictures a dreamlike woman, wearing a rabbit's head or a prickly pear, holding a snake or a tree branch. "Without Her" is a complex image of death. The deceased woman floats among ferns, her white dress billowing around her, her limbs slowly detaching.

In "Blind Faith," a lovely work in white against soft blue-gray, a blindfolded woman strides forward, making her way through a surreal shower of shapes, boldly going where no woman has gone before.