Up on the second floor of Tucson's beloved Benedictine Monastery, there's a sunlit room that once served as a sewing room for nuns. The long tables in the space were perfect for cutting the cloth for their habits, and from the windows the sisters could see leafy trees swaying in the breeze.

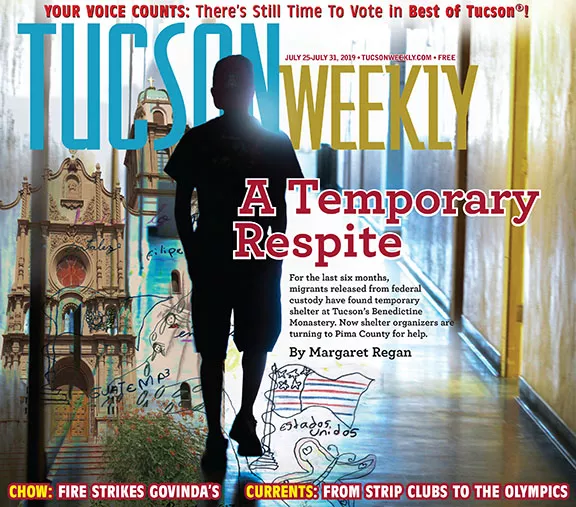

For the last six months, children fleeing the horrors of Central America have replaced the nuns in the cheery room. The sisters sold the property in 2018 and in January, Catholic Community Services turned the 79-year-old monastery into a temporary shelter for families seeking asylum in the U.S. They called it Casa Alitas, House of Wings.

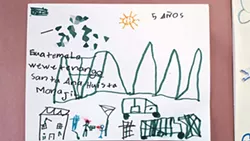

The old sewing room was converted into a sun-dappled art classroom and gallery, and nowadays the children ply their markers and watercolors as diligently as the nuns once stitched their fabric.

On a bright morning this summer, a passel of kids, fresh from dire conditions in a Border Patrol short-term lock-up, sit in eager attention at the tables. Starved for kindness and for a regular school routine, they call the smiling volunteers, many of them gray-haired grandmas, "maestra" (teacher). The lead volunteer, artist Valarie James, whose own work on migration has been displayed internationally, created the clase de arte. She stands at the head of the table and invites the children to "paint what you love."

From toddlers to teens, the kids dive in. The littlest ones, seated at a kindergarten-sized table, scribble with bright crayons on paper, their beaming mothers and fathers squeezed in beside them on tiny chairs. Slightly older kids at the big table draw simple houses—quite a few of the little boys make trucks—but the big kids, the middle-school agers and teens, turn out beautiful watercolors of the lands they've left behind.

Lyrical flowers, horses, trees and mountains dance across their artwork. Ana meticulously draws a whole forest of green trees. Sixteen-year-old Rosa paints a brilliant watercolor: green in the foreground, a trio of pointy mountains in the background, and the blue waters of a lake in the center.

"That's Lake Atitlán," she tells me in Spanish. Her doting father, standing nearby, says he and his daughter lived near the lake in the Guatemalan town of Sololá, but the two of them are heading soon to North Dakota to reunite with his brother.

Like the others in the room, Rosa and her dad will be at the shelter only a few days. All the people at the shelter are legally in the U.S. They've already been processed by Border Patrol and once they get bus tickets, they will travel legally to destinations around the country where their sponsors—and immigration judges—await them.

James walks around the room, doling out praise generously to the budding artists. She's not surprised to find the three peaks in Rosa's painting. Lakes and mountains and forests are "what these rural kids know and love," James says, and landscapes are the most common subjects in the shelter's Galleria de Niños—the walls where children proudly hang up their masterpieces.

But not all the pictures the kids make are joyful. One girl in the class is carefully constructing a drawing of all the family members she's left behind in her homeland: her mom, her baby sister, her brothers, her pets. She's solemn as she points to each one, sadly reciting their names.

Others make wrenching images of the perils of their countries and the travails of their long journeys to the U.S.

At City Council member Steve Kozachik's nearby Ward 6 office, where the refugee children's artwork is on view through August, one pencil drawing shows a family of four trapped on the wrong side of the border wall; scary Border Patrol vehicles guard the other side.

An unspeakable murder haunts a 5-year-old from Guatemala. The little boy used markers to draw his country's ubiquitous mountains, but below the pretty peaks a crime is taking place. A man is shooting a gun at another man's head and a torrent of red blood rushes out of the dying man's body.

"There's all kinds of human tragedy here," says Kozachik, who brokered the deal with the monastery's current owner to lend the building to Casa Alitas for six months. The shelter's "guests," as everyone calls the asylum seekers who spend a few days there, "tell stories of extortion, rape, murder, dismemberment," he says. A young woman lost two children (in her home country) and came here to restart.

"I take folks through the monastery for one hour. I remind them, you look in the eyes of these kids and in the eyes of their parents and you will see the story of Central America."

Casa Alitas, a program of Tucson's Catholic Community Services, is much in the news these days. It has to vacate the monastery by Aug. 6, per agreement with owner Ross Rulney, a developer who is set to build apartments on the property while preserving the venerable building. Earlier this week, after a contentious meeting, the Pima County Board of Supervisors voted to use vacant pods in the county's juvenile detention center as a central waystation for migrants.

But Casa Alitas is by no means the only shelter in Tucson welcoming distraught asylum seekers, who, it can't be repeated often enough, are legally in the U.S., having passed the first "credible fear" test administered by agents at the border.

The Methodist Church has two shelters, one of them The Inn is a large operation in midtown and the other is in the foothills. Likewise, two Presbyterian churches, a United Church of Christ congregation, a First Christian Church and the Salvation Army welcome the strangers. All the shelters give them respite from their travels for a few days before they depart again to destinations all over the U.S., from South Dakota, where Rosa and her dad are headed, to New York, Oregon and Florida.

CCS has won kudos and national attention for the loving care it's given more than 10,000 asylum seekers at the monastery since January.

"We get a lot of media," says Teresa Cavendish, director of operations for CCS. "It helps us change the message of an 'invasion' of people taking advantage of the U.S. Our obligation is to help suffering where we encounter it."

Some 40 spartan bedrooms where the nuns once prayed, along with a few larger bedrooms and vast finished basement filled with cots, have allowed the shelter to host up to 250 of these suffering people in one night. When there are just too many guests for the old monastery to handle, they are transported to the sister shelters that have beds available.

Casa Alitas provides a dazzling array of services, delivered by 400 or more welcoming volunteers, many of them retirees. Three homemade meals a day are offered in the comedor, migrants can pick out clothes and shoes in a place that looks like a thrift shop, transportation volunteers help them buy their bus tickets. (Families send the money). Tech wizards put the schedules on computerized screens, locals are enlisted to shuttle families to Greyhound. Each of the travelers leaves with a backpack stuffed with food and toiletries for the journey.

Every arriving person gets a medical screening and, if necessary, a thorough exam from one of some 180 medical professionals who volunteer their time. Badly injured and ill people are taken to hospitals.

In one of the shelter's worst cases, says Cavendish, "A dad and son from Honduras were riding on top of a train," the notorious bestia—beast—that impoverished migrants ride clear across Mexico. "The dad got dizzy and fell. He lost an arm and a leg, and had an injury to his other arm. He was in the hospital for over a month."

Border Patrol agents routinely take medicine away from their charges, Cavendish says, a practice that is particularly dangerous to children and adults with seizure disorders.

"Docs say you shouldn't mess with such meds," says Cavendish. If the shelter can't find the appropriate drug, the patients must go to the hospital.

"Mostly we see people who were injured on the journey—extreme dehydration, rashes, blisters on their feet from walking," she adds.

But today a little girl has been brought in directly from the hospital. Nurse-practitioner Audrey Russel-Kibble discovers that she's recovering from chicken pox. Audrey determines the girl will be able to travel in a few days, but at the monastery she must be kept isolated—she can't play with the other kids and she and her mother will be placed in a private bedroom.

With all the cases they see, Cavendish says, medical and nursing students are getting field hospital experience, right here in the USA.

The beauty of the monastery provides a bit of respite from all the sorrow. Set in the nuns' beautiful gardens and orchards, where children ride bikes and parents relax under the orange trees, the ornate structure is a glorious piece of Spanish Colonial Revival architecture. Benedictine sisters who arrived in Tucson in the 1930s commissioned Roy Place—the revered Tucson architect who also designed the 1929 Pima County Courthouse—to build them a new home. Place worked partially on an earlier design by Josias Joesler.

Finished in 1940, the building has a turquoise tower soaring toward the sky and a pink domed sanctuary where the nuns once sang vespers and attended Mass.

Arriving guests, dropped off by ICE or Border Patrol, often think they've been brought to yet another detention center. But when they walk into that pink sanctuary they're told "you're free."

Some intake volunteers swear that the serene space helps soothe the anxious guests, most of whom are burdened by multiple traumas—the violence and deprivation in their homelands, the difficult journey north, perhaps a stay in a Mexican border shelter, and finally days and nights in the U.S. in freezing Border Patrol holding tanks, where there's bad food, lights overhead 24-7 and open toilets for all to see.

And sometimes the sublime architecture takes on another task: buoying the spirits of the stoic volunteers who listen daily to these tragic tales.

On this particular day, when 120 guests are already at the shelter, Border Patrol calls to tell Cavendish to expect 20 people shortly, but the van is late, as it frequently is.

Hermano Juan—Brother Juan—is mopping the floor in the sanctuary, making the place spic and span for the newcomers. He doesn't seem to mind when the sudsy water splashes his brown monk's habit.

"I clean the floor and the pews," he says in an English accented by his native Spanish, a language that comes in handy at the shelter. While he's working, an anxious woman tells him she urgently needs to make a llamada—a phone call—back home. Juan lays down his mop momentarily, and takes her to the office.

Juan and his fellow monks take turns driving up to Tucson a couple of times a week from their home in Elfrida to do whatever needs doing, he explains.

"We go outside the community. Our goal is to reach out to those in society that nobody wanted."

When the new guests arrive, they walk across Hermano Juan's glowing floors, and sit in the pews left behind by the nuns. While they await their turn with an intake volunteer, their faces are lined with worry.

Four mothers and four daughters from El Salvador sit in a pew together while two kind nursing students from the UA start doing a preliminary health interview. One of the travelers has already had a rough moment: she was searching through her purse and at first could not find the crucial government document that allows her to travel in the U.S. lawfully. Now she's found it, and the nurse is asking her if she has piojos. Lice.

The woman frowns. She doesn't know the word, at least not the way the high school translator pronounces it. So the enterprising student nurse puts her hands on her own hair and frantically scratches her head, mimicking an itchy victim of lice. The guest is dumbfounded for a second and then begins to laugh heartily. "No," she says in Spanish. "No, I don't have lice."

She cheers up even more when a helper delivers some broth for her and her daughter. After days in custody, unable to give the child the food she needs, the woman pulls her little girl up onto her lap and feeds her, lovingly spooning nourishing liquid into her mouth.

The migrants complain about the Border Patrol food, a fetid combo of frozen burritos (sometimes not defrosted), crackers and suspicious water, served at random times, including in the middle of the night. (One of the art pieces in the Ward 6 show is a satirical jab at the Border Patrol diet, headlined No más burritos. No more burritos.) More seriously, one man today complains that his wife vomited when she bit into a burrito earlier in the morning and has had a splitting headache ever since.

The volunteers reintroduce food carefully. People who eat too much after eating too little can get sick, and they've vomited in the sanctuary. Water, fruit slices and broth are available immediately. If those go down well, then the person gets a bowl of hearty soup.

A rambunctious little boy from El Salvador, perhaps 3 years old, is sitting with his mother and little brother. The mom is anxious. She holds onto a plastic bag filled with her meager belongings, and tries to wrangle the two wiggly boys as she awaits her turn at intake.

A volunteer soon approaches with cups of broth. The boy grasps the cup and gets his first taste, then comes up for air with a delirious smile. And when he moves on to the hearty soup, he's in seventh heaven, wriggling and almost dancing in his seat. When a volunteer asks him, "¿Te gusta?" Do you like it? He laughs out loud.

Elsewhere, in the kitchen, David Lawrence is putting final touches on the day's lunch.

"We always have soup and always rice and beans," he says, gesturing to the mega-bags of beans and rice stored along a wall. The other perennials on the menu: fresh salad, fruit, tortillas and dessert.

Stacks of food are everywhere, all of them donated by Tucsonans. Sweet treats, cookies, banana bread and cupcakes are ready to go. Mothers are always asking for fruit for their children, and the monastery delivers with oranges, bananas and watermelon.

Coffee is always available in the comedor, the dining room, and while Lawrence sets out the food, a group of adults linger with a hot cup. They're relaxed and enjoying a conversation with a visiting American nun, who happens to have served in the village right next to theirs in Guatemala.

"I think these people are great," says Lawrence, a retired home builder. "They're very gentle. They're cheerful, and they jump in to help. They're grateful for our services. There's a big need here."

Sometimes, when a huge number of guests are dropped off unexpectedly, "it can be a scramble racing to get food ready," he chuckles. "But it's fun when it's chaotic!"

Down the hallway at the free clothes shop, a little boy is trying to persuade his mother that the totally cool and way-too-big sneakers he's picked out are the right size. A mother with a 5-week-old baby asks for a rebozo, a winding cloth that binds a baby to its mother's chest. A clever volunteer improvises by cutting a giant scarf down to size. The new mom deftly takes it and winds it around her little one. Everyone's gossiping about the monastery's other baby: a 3-day-old infant is upstairs with her mother, both of them attended by a volunteer nurse. In the hallway, an older volunteer is lugging a heavy bag of clothes to the shop. A Guatemalan man, on his way to get some clothes, notices her and leaps up to shoulder her burden.

Casa Alitas became generally known during its seven months in the monastery, but it began five years ago, when the worsening catastrophes in Central America forced thousands of desperate women and children to flee. Tucson learned about this humanitarian crisis on Memorial Day 2014, when some 80 refugees, including babies at the breast, were unceremoniously dumped by Border Patrol at the Greyhound bus station, starving and freezing after days in the local Border Patrol lock-up.

I was reporting that evening, and the stories those refugees told me then are exactly like those we hear today. Women at the bus station were chilled to the bone from days in the hielera or icebox—the punning name for a freezing ICE jail—and distraught that their babies were deprived of milk and their older children barely fed.

When activists arrived with fast-food chicken and milk, the ravenous kids gobbled the food so fast some of them got sick. One frantic woman told me that the Border Patrol had taken away her two little nieces; she had promised their mother—her sister—she would bring them to her in Florida. But since she was the aunt, not the mother, the agents classified the girls as unaccompanied minors.

Within the next few days, 400 women and children were flown from Texas to Tucson. The small Tucson activist group Casa Mariposa strove valiantly to feed and shelter them and get them on buses to travel across the country to loved ones. But there were more people than they could handle.

Under CEO Peg Harmon, Catholic Community Services stepped up and opened a shelter in a midtown house they owned, and christened it Casa Alitas. (CCS also enlisted folks to host travelers in their own homes.) Following the Casa Mariposa protocol, at Alitas the travelers could rest, eat, line up bus tickets, get a ride to the bus station and get food and toiletries for the journey. In other towns, including Oracle, protesters had turned out to scream at the mothers and babies in buses, so in Tucson, for safety's sake, Border Patrol and ICE agreed to bring the guests directly to the Casa house.

Over the next four years, the numbers of migrant families arriving from custody waxed and waned. But suddenly, in October 2018, the numbers skyrocketed, as fathers and mothers escaped with their children from the deteriorating conditions in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

Americans rarely consider the damage we've done to Central America over the last 60 years, propping up murderous military dictatorships, turning a blind eye to the international agro-corporations that are pushing impoverished indigenous people off their land.

And even as President Trump charges that the asylum seekers' claims are bogus, the U.S. State Dept. warns Americans of the dangers of traveling in Central America. In an April 1 travel advisory, even embassy employees were urged to stay away from the perilous western highlands of Guatemala—the very places that so many asylum seekers are now fleeing in fear for their lives.

The State Dept. warns Americans to stay out of Honduras and El Salvador altogether. In all three nations, the State Dept. writes: "Violent crime, such as armed robbery and murder, is common. Gang activity, such as extortion, violent street crime, and narcotics trafficking, is widespread. Local police may lack the resources to respond effectively to serious criminal incidents."

But after the October surprise, critics accused the Border Patrol of "hoarding" the asylum seekers for days and then deliberately releasing them in large batches to scare voters in the run-up to the mid-term elections.

"Follow the Trump tweets," Kozachik said recently. "He proclaims an emergency. Then we get a call from ICE: 'You'll get 150 people.' I am not alone in speculating that this is political. Refugees are being used as political pawns to create a crisis."

The shelter workers in Tucson pride themselves on taking on anything Trump throws at them, and taking care of all the people in need who come their way, no matter how many. In response to the 2018 October border surprise, they mounted a rapid-fire operation, filling their own established shelters with families and enlisting fellow churches to take in people temporarily. CCS started renting motel rooms to supplement their Casa Alitas house.

But then came an offer made in heaven: a Tucson developer invited Casa Alitas to temporarily set up a giant shelter in the Benedictine monastery. For free.

Tucsonan Ross Rulney bought the monastery and its six blooming acres back in 2018, but his relationship with the monastery's neighbors was rocky from the get-go. His original development plans called for tall apartment buildings, some 86 feet high, but they provided for preserving the monastery. If neighbors balked at this plan, he could sell the whole property to a student housing company. Worse, a company with no ties to Tucson just might demolish the cherished monastery, which was not protected and has no status as a landmark building.

Tucsonans were aghast that the city could lose the lovely monastery. Ultimately, after many negotiations, Rulney relented. He agreed to build shorter buildings, four-story (45 feet) and five story (55 feet) tall, and to create luxury apartments, not student housing. And he agreed to preserve the monastery and allow for some public use there.

Council member Kozachik filed for historic landmark designation to protect the monastery in the future, even if it's sold to another party. "The building will be preserved," he says.

After this rough start, Rulney won some good will in the community by lending the building free of charge to Casa Alitas for six months.

"Ross deserves a lot of credit," Kozachik says. "He has not charged us rent. He's paying $4,000 to $5,000 a month on utilities. He brings food over."

The Casa Alitas gang took Rulney up on his offer and got right to work turning the old place into a shelter. The nuns sent their good wishes, and Tucsonans flocked to help out.

In the months since, the numbers of asylum seekers have see-sawed up and down. On at least one night, Casa had 250 guests sleeping overnight. On Easter weekend there were so many that Pima County and the City of Tucson both jumped in to create temporary shelters. Kozachik has opened his office half a dozen times, deploying enough cots to house 50 people each time. More recently, as harsh new policies like "remain in Mexico" have trapped asylum seekers on the south side of the border, numbers have dropped. But predictions are useless. A day last week that saw only two guests arrive was succeeded by a day with 50 and counting.

The crowds, large and small, have put a strain on the old place. The plumbing was cranky from the start. Ceiling leaks plagued the comedor and overworked toilets broke down. Fixes were tried and money was spent, but about two months ago, the Casa managers gave up.

A phalanx of port-o-potties have now been installed outside, as well as a portable shower trailer and three homemade showers. That means that families with little kids needing to go have a long walk through the monastery's labyrinthine corridors. Guests are asked not to go out at night, so they can't make bathroom stops in the midnight hours.

The indignities of that bad plumbing in part colored CCS's search for a replacement shelter. Cavendish and team looked for several months for a suitable replacement. Two weeks ago CCS announced a tentative deal to locate Casa Alitas in three wings of the massive Pima County juvenile detention center on Ajo Way. The plan was approved by a 3-2 vote of the Pima County Board of Supervisors earlier this week, with Democrats supporting the plan and Republicans opposing it.

The shelter will be walled off from the sections that still house detained teens. In an effort to make the place homier, the walls are already being painted cheerful colors. Common spaces will be carpeted, and Casa Alitas can bring in comfy couches and toys. Each wing adjoins a fenced and covered outdoor space where kids can play. Most of the food will come from the institutional kitchen, but Cavendish says they'll aim to have volunteers bring in at least one "culturally appropriate" homemade meal a day.

Most importantly, the space can hold up to 300 people, and there are plenty of showers and toilets.

Even so, a prison-style toilet is nailed to the floor inside each of the small, windowless bedrooms, just steps away from the bed. And the enormous building, outfitted with plenty of chain link, is isolated from the neighborhood. CCP's plan to house traumatized asylum seekers in empty wings of an active detention center has set off a painful rift. To many activists, including some of Casa Alitas' close shelter partners, say it looks like a grim jail, and they have loudly objected to the plan.

"Our efforts can change this space," Cavendish says, responding to the critics. "We don't have time to wait and let this play out."

And she pledges to re-create the loving, welcoming atmosphere of the monastery, with the help of volunteers like Hermano Juan, David Lawrence and Valarie James.

The clase de arte can thrive anywhere, James says. "I'll teach the kids no matter where we are."