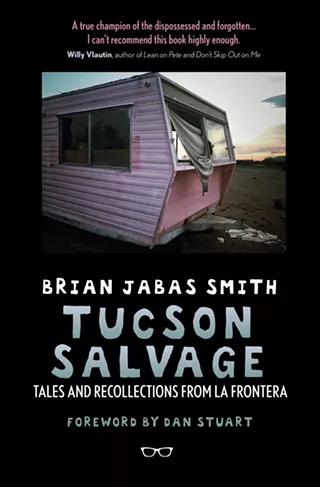

Award-winning journalist and author Brian Jabas Smith has a new book of columns and stories, Tucson Salvage: Tales and Recollections from La Frontera, out November 1 on Eyewear Publishing UK. The book is based on the last three years of his column, Tucson Salvage, which runs every other week in the Tucson Weekly.

You've said that you came home to Tucson three years ago, maybe, to die. What did you find here that made you stick around?

Family. My sisters and brothers. Connections to my father and mother, who are both gone. And Tucson. After living in Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Detroit, I began to understood simple truths of home, the familial bonds and self-idealization, that classic "going home" trope. Also that Jim Harrison thing of emotional contrasts, about how damnation and redemption are corollaries of returning home. I found that the non-challenge of coming home to a place that's emotionally safe—a place to bask in nostalgia—is a real test in itself. Because I was quickly reminded when I got here that there's no emotionally safe place on earth. It's just a story I was telling myself about my hometown to feel better. To counter suicidal thoughts. Turns out you don't go home simply because your standards are low. For me the opposite turned out true, and I got to explore why with Tucson Salvage.

Yet what makes it difficult now as a resident is witnessing certain attempts to conceptualize Tucson as an up-to-the-moment boomtown on the edge of technology and culture, like what happened in Austin. If you try to be that, you ruin it. Remember, no one can afford to live in Austin now. it's over-populated, overrun, its culture diluted. It's over. Was a city built on music but the venues and bars can't even sustain the downtown rents anymore. This is America. Be careful what you wish for. I understand craving heightened living, and I understand the idea of community, but the greed sours. In Tucson, like Austin, it's the white liberal elite inflicting damage, and I'm as left as you can get. It's so deceptive.

Tucson is a dusty little town wanting to be a city. Thank whatever gods we ever heard of it ain't a "city" yet. It's a wonderful place of contrasts. It's the eighth most impoverished city in the country, yet one of the most beautiful, historic and storied. It's strikes a bittersweet balance of hope and despair. That's where I like to live, where that melancholy lives. Probably not for everybody.

What is it about Tucson that you love the most?

Sometimes just the way sundown light refracts off the Rincon Mountains sends chills through me that carries an emotional weight no other place on earth can duplicate, and my own head can't ever duplicate. It's a kind of sadness, really. A lovely kind of sadness. Tucson's filled of small wonders, in its neighborhoods—the dusty creosote, the barking dogs behind chainlink, the crooked mailboxes. The shirtless adult men with too many DUIs flying down Flower street on kid bikes, shuttered businesses baked out by brutal sunshine. How the piquant odor of Javelinas arrive before they do.... The end-of-the-world quality of the Sonoran, and all her blossoms, scents and ghosts. So many things send me.

I feel that tingle of sadness in other American places but to a lesser degree, like in the Hollywood Hills, those haunted neighborhoods. California is not my home.

I feel it in Detroit, at 7 Mile and Livernois, at Grand Avenue and Linwood. Detroit is haunted too. And holy, the spirits and the past, the present, its ruins and menace. But Motown is not my home.

We make legends of our places in our hearts, in our hometowns, and I have many very personal ones here, some before my time, both beautiful and frightening—from Charles Bowden and Our Mother of Sorrows to Charles Schmid Jr. and any traveling carnival that sets up on 22nd Street, Pearls Hurricane Bar, now my wife and son, and so on. Still, the frayed remnants of '60s idealism still exists, but feels like it went here to die, and that's fascinating. Even on beautiful Fourth Avenue.

The gigantic Hispanic population, the whole other city of Tucson on 12 Avenue, and that fascinates. So much here.

You've said that writing about people in Tucson Salvage is a way to exercise empathy. What are the most challenging people for you to interview? Do you ever find it hard to feel empathy?

Empathy just is, I guess. It's an abstract to me; nothing willingly produced, right? I always try to have compassion. I will say the women and men I meet and write about often suffered moments in life when things went tragically sour for whatever reason, and there was little they could do about it, yet they managed to overcome. My favorites are those who've gone to battle in some way, and who never got the breaks, and emerged walking, talking giants.

But it is tricky. I sat down with this guy once who had a family and he was hurting bad, just riddled with poverty. He'd opened a 24-hour head shop in town by counting up family nickels, and a good-faith business note from the previous owner. I liked this guy at first. African-American, from Louisiana, not pulling punches in the good fight, right? Well, by the second meeting it felt off. He'd gathered his family in the back of the head shop for an "interview." They carried themselves as if heavily coached by dad beforehand, really mannered and only looking at dad before answering a question. This sense of control felt creepy. I checked police records, which you have to do. Turns out the guy did jail time for child molestation. He wasn't upfront about it. Maybe that could've been the story, I could've just knee-capped the guy in print, but I couldn't bring myself to write it all. Just sickened. Never talked to him again, of course. His business soon went south.

Why do you think that telling these stories is so important? Is it more important now in the age of Trump's America? Why?

My friend Dan Stuart, who penned the book's foreward, said it's about giving voice to the voiceless. That sounds really noble, man. At best I think I'm sort of diagramming certain subtleties and tensions of our existence. It's what I've always loved in fiction, in my favorite authors, from Truman Capote to Flannery O'Connor to Denis Johnson to Tom Wolfe.

If anything's "important," then it is telling stories that'd never be told otherwise. I'm far more in love with the mundanities of a working-class existence. Look closer and every one contains some life-altering event and tremendous sadness or tragedy. Sure, the woman at the methadone clinic cuts herself but she's still only recreating the beatings she received as a streetwalker, a career path for a girl horribly molested by her father. Yes, the state took her children. But she found love, and she's intelligent and she's in an apartment now and not homeless. Listen close and there's something that's universal. Maybe some personal truth rings out and we don't like it. That's the kind of cultural story I love, more than any other kind of personality driven piece.

I've made albums and done tours and I've written countless words about people who've done that too and it bores me. I can't read such pieces anymore either, can't write them anymore. The heroes exist in the day-to-day, the teachers, the vets, the homeless, the artist with no legs making a prettier world. And I've been homeless too, and an addict, and learned to live on less then $5K a year. It's a miracle I'm alive, much less writing. It's what I know. I'm far more interested in people few others care about, the guy at the bus-stop everyone ignores but who is hearing voices of his wife who died in car accident three years ago. The Hispanic woman and her mother selling salvation in sugar in a kiosk on wheels on lonely stretch of 22nd Street at 10 p.m., both of whom snuck across the border. I'm just grateful some others are reading.

For me, writing non-fiction is harder than fiction, because there's so much to overcome personally, my own wretched insecurities for one, having to meet complete strangers and then earn their trust enough to get a dialog going.

So damn worried about what they think of me that sometimes I miss the story. I often get sick in my stomach before I go out to do a story.

Do you ever think about expanding your column to include people in greater Arizona or nationwide?

Yes and no. I am forever attached to the Southwest. But lurking on any corner is a something worth telling not polluted by social-media branding and grim look-at-me deeds. The more people are misunderstood by privileged standards, the more I want to write about them.

Do you feel like these Tucson stories are universal? If so, why?

Universal? Absolutely. This is where we live, all of is. We all must earn money to eat, provide a roof and water, food for a pet even.

You chose to go with an international publisher instead of a local or regional one for your new book. Could you explain a little about what went into that decision?

Well, I was turned down by one regional publisher. Then Eyewear Press in the U.K.— who my Spent Saints editor and renowned poet John "Cal" Freeman put in touch with me—made an offer. We didn't shop the book to any other publishers. We wanted to get this out fairly quickly because Spent Saints did well, at least by small literary standards.

Eyewear sees the Tucson Salvage stories as representative of America today, not a regional collection of columns. Said it shows who really lives in America now. Maybe it took an overseas editor and publisher to see it that way, but I'm grateful.

My original plan after Spent Saints was to release either another collection of short stories or a novel. But these Tucson Salvage stories keep telling a bigger story, about people, about (un)living wages, about the American experience. We traveled so much of last year on the book tour, which seemed never-ending because the book sold steadily over the long haul. We saw so much of this country first-hand. I'd walk through the neighborhoods, the downtowns, the streets. Meet so many people. And the stories are the same everywhere, and a sense that we've got five years left of the American life and that's it. Whether that's true or not is irrelevant. Fact is, there's all this brokenness and poverty and ruin of the American dream, but there's so much beauty there too, in ways people are figuring out how to get by. That struggle. That, and how things constructed in our recent lifetimes—from housing subdivisions and strip malls to hand-held technologies and war chicanery—don't age well, so we get to literally watch even our recent culture decay.

There is a documentary already produced which has some of the people you've interviewed telling their stories on camera. What is it like for you to watch the film? Is it strange to see your written work interpreted into the filmic medium?

Well, my wife Maggie, who's a mighty gifted filmmaker, I will say, directed the film, and it stuns. It captured subjects from the book with real grace, the kinds of grace I strive for. These subjects, some tragic, are all beautiful in their ways. The film is journalistic because it's pure storytelling minus varnish, and that's its grace. It is flattering beyond words to see some of the stories on film; how writing transcends medium. It's disquieting to see these underrepresented people show themselves with no filters. They're brave as shit. It validates the work too. It shows how people will relate to world with some courage, when they are given the chance. And it looks like how I see Tucson.

What is the story in the book that you are proudest of and why?

A story called "Still Life at the Chatterbox." The Chatterbox Lounge is an old Tucson bar on Alvernon Way, a fading strip near Davis Monthan Air Force Base. I walked in one night, literally with a pen in hand. Leak in the ceiling, swamp-cooler wheezing, old rotisserie hot dogs you could smell. Absolutely nothing happened in there. Nothing, except a conversation with the bartender and her boyfriend, who was stepping in and out. Like a one-act play. I wrote it all in second person, which is almost silly. I think I captured some hope and despair in that place. But more importantly, I learned about myself, my judgments, the way I see others, my perceptions, and how we never really master ways to talk about the unsettling areas in life.

You reveal a lot about your own life and struggles through writing about other people's lives and struggles. Does your own changing narrative—from alcoholic/addict/loner to family man—shape the way you approach stories? Are you drawn to different individuals now that you are a father?

If anything, I'm fighting off depression and panic daily to be a father to this 5-year-old boy. He's a remarkable kid, and I learn so much from him about how we react to things in our lives. Like how my default button is depression. Well, his default button is pure joy and curiosity, where there is no resolution, not moral, not ethical, not even how the day unfolds, just joy. How did I ever lose that? Did I ever even have that? Doesn't matter now. Watch the boy.

And no, I'm not drawn to different people. If anything, I have a greater sense of compassion for the world because of this boy, this family. Sometimes I can't believe I'm here at all.