Friday, April 15, 2022

Migrants wait at the border while U.S. battles over lifting COVID-19 ban on processing asylum applications

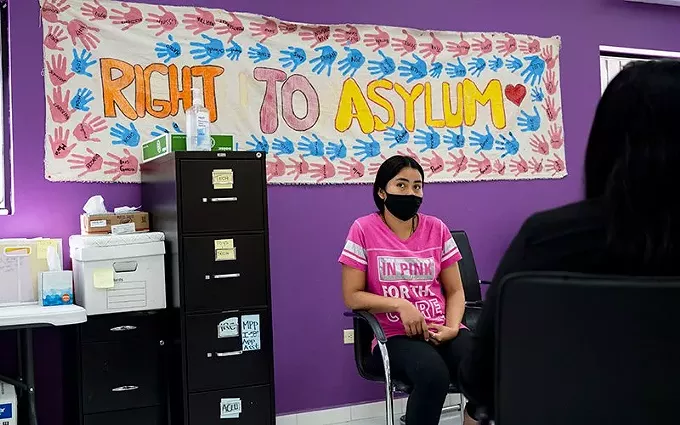

Photo by Genesis Alvarado/Cronkite News

Rosario, 24, an asylum seeker who only wants to use her first name for protection, says violence pushed her out of her home state of Michoacán. She talks to a Cronkite News reporter in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico on April 13, 2022.