Monday, August 17, 2020

Miss Navajo Nation is a ‘glimmer of hope’ for community during pandemic

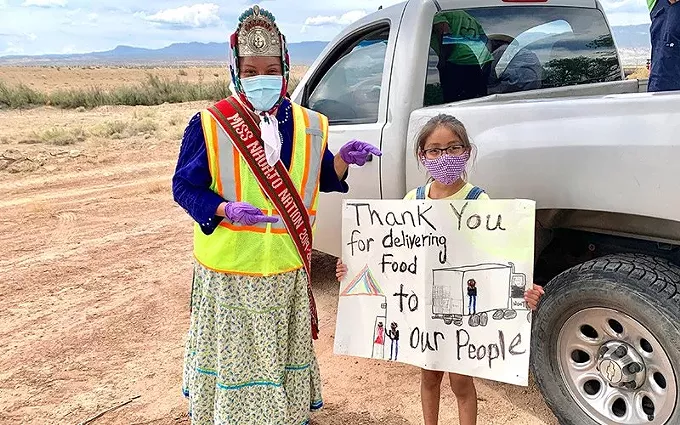

PHOENIX – After winning the title of Miss Navajo Nation in September, Shaandiin Parrish immediately got to work on the cultural preservation and advocacy efforts central to the role.

At times, she attended five or more events in a single day, traveling across the 27,000-square-mile reservation to speak to elementary school students and attend conferences.

“You really hit the ground running,” Parrish recalled. “There’s no event too small. There’s no event too big.”

But in March, as COVID-19 swept through the Southwest, Parrish suddenly went from visiting elders and delivering motivational speeches to distributing food, supplies and information to Navajo families hit hard by the novel coronavirus that causes the deadly disease.

In the months since, Navajos have turned to Parrish for information, encouragement and aid as the virus killed at least 462 Navajos and sickened more than 9,000 others.

“I had a voice as Miss Navajo,” she said. “I never had a second thought about helping.”

A ‘sacred’ responsibility

The title of Miss Navajo Nation is won at an annual pageant established in 1952. The competition, held during the Navajo Nation Fair, tests contestants’ ability to handle tasks ranging from modeling traditional wear to butchering a sheep.

During her one-year term, Miss Navajo Nation serves as a goodwill ambassador for the executive branch of the tribal government and a “beacon of hope” for the community. Her role honors the matriarchal structure of Diné society and provides an example of strong female leadership for the tribe.

“Miss Navajo Nation represents all of the female deities, the female beings and all of the Navajo women that exist,” Parrish said, calling the responsibility both “sacred” and “huge.”

“To the public, you become everybody’s mother, sister, auntie, their friend. You become the mother of the people,” she said. “It’s important to me to represent with dignity, power, strength and just the beauty of Navajo women.”

The position is a full-time job: Miss Navajo Nation cannot work elsewhere or go to school during her year of service. She also is expected to consistently appear positive, healthy and strong to show she can “endure and be in the spotlight.”

“There’s just so much to do within one year … it’ll wear you out,” said Alyson Shirley, who held the title in 2015-16. “I know some former Miss Navajos that were hospitalized toward the end (of their year) because they were just so exhausted.”

And they weren’t dealing with a global pandemic, as Parrish is.

Travel now done ‘out of necessity’

After COVID-19 hit, she became a public information officer for the Navajo Nation Health Command Center. The role is crucial when it comes to getting information about preventive measures out, she said – especially to elders who speak Navajo only.

“With our reservation, there are two languages that we need to translate everything into,” Parrish said.

She also helped out on the front lines, distributing food and supplies to families in need despite the risk of contracting the virus. There are just 13 grocery stores on the vast reservation, she said, meaning some families would have to travel for hours to stock up if they didn’t receive aid.

“We keep our people out of clustered places and allow for some relief for a week or two, so that they don’t have to risk going to a crowded supermarket,” Parrish said.

Instead of allowing invitations to determine her travel schedule, as she did before the pandemic, Parrish said she now travels “out of necessity” with presidential approval.

But expectations regarding making every interaction with her people a positive one haven’t changed.

“It’s important to keep a balance and positivity whenever I get to interact with them, because what if they had a really bad day and somebody is dealing with domestic violence, or somebody is not getting paid and they need food?” she said.

“I need to leave that positive impression to ensure that they know that they’re loved, that they’re cared about and their lives are important.”

‘Not just something glamorous’

Parrish’s efforts moved rug weaver Marie Nez-Gamble to make a sash for Parrish, to show her family’s appreciation for “the amazing things she does and has done and will continue to do for our community.”

The sash took Nez-Gamble 36 hours to weave.

“She just really inspired us and just really didn’t hold back,” Nez-Gamble said of Parrish. “She educates young and old, encouraging them to continue their education, continue to speak their native language and learning their native culture.”

Crystal Littleben, who was Miss Navajo Nation in 2017-18, also praised Parrish for “putting herself out there” during a dangerous time.

Littleben, who already lost relatives to COVID-19, said she couldn’t assist her community the way she wanted to because she’d never forgive herself if she brought the virus home.

“It’s a hard task to take on,” Littleben said. Parrish “knows all those risks, and she probably has to distance herself from her own family just so that she can help her community that way.”

Shirley said Parrish has shown the title is a real service job, “not just something glamorous.”

“When she came to my community, there were a lot of the elderly that were happy to see her in her Navajo traditional attire handing out things,” Shirley said. “They were looking at her as a glimmer of hope, and they were saying, ‘We’re going to be OK. We’re going to be OK.’”

Parrish acknowledged the mental and emotional toll the pandemic relief efforts had taken on her, but she has no plans to step back.

Her latest aid project has the ambitious goal of ensuring that all 173,000-plus Navajos living on the reservation have five face masks each – and she’s sewing many of them herself.

“I know that our people need to see our leadership taking this on,” Parrish said. “I’ve really had to set aside my own emotions, my own thoughts, my own opinions about anything and everything that’s going on around me.

“The well-being of our people comes first.”

This story is made possible through a partnership between the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict at Arizona State University, with the support of the Henry Luce Foundation.

At times, she attended five or more events in a single day, traveling across the 27,000-square-mile reservation to speak to elementary school students and attend conferences.

“You really hit the ground running,” Parrish recalled. “There’s no event too small. There’s no event too big.”

But in March, as COVID-19 swept through the Southwest, Parrish suddenly went from visiting elders and delivering motivational speeches to distributing food, supplies and information to Navajo families hit hard by the novel coronavirus that causes the deadly disease.

In the months since, Navajos have turned to Parrish for information, encouragement and aid as the virus killed at least 462 Navajos and sickened more than 9,000 others.

“I had a voice as Miss Navajo,” she said. “I never had a second thought about helping.”

A ‘sacred’ responsibility

The title of Miss Navajo Nation is won at an annual pageant established in 1952. The competition, held during the Navajo Nation Fair, tests contestants’ ability to handle tasks ranging from modeling traditional wear to butchering a sheep.

During her one-year term, Miss Navajo Nation serves as a goodwill ambassador for the executive branch of the tribal government and a “beacon of hope” for the community. Her role honors the matriarchal structure of Diné society and provides an example of strong female leadership for the tribe.

“Miss Navajo Nation represents all of the female deities, the female beings and all of the Navajo women that exist,” Parrish said, calling the responsibility both “sacred” and “huge.”

“To the public, you become everybody’s mother, sister, auntie, their friend. You become the mother of the people,” she said. “It’s important to me to represent with dignity, power, strength and just the beauty of Navajo women.”

The position is a full-time job: Miss Navajo Nation cannot work elsewhere or go to school during her year of service. She also is expected to consistently appear positive, healthy and strong to show she can “endure and be in the spotlight.”

“There’s just so much to do within one year … it’ll wear you out,” said Alyson Shirley, who held the title in 2015-16. “I know some former Miss Navajos that were hospitalized toward the end (of their year) because they were just so exhausted.”

And they weren’t dealing with a global pandemic, as Parrish is.

Travel now done ‘out of necessity’

After COVID-19 hit, she became a public information officer for the Navajo Nation Health Command Center. The role is crucial when it comes to getting information about preventive measures out, she said – especially to elders who speak Navajo only.

“With our reservation, there are two languages that we need to translate everything into,” Parrish said.

She also helped out on the front lines, distributing food and supplies to families in need despite the risk of contracting the virus. There are just 13 grocery stores on the vast reservation, she said, meaning some families would have to travel for hours to stock up if they didn’t receive aid.

“We keep our people out of clustered places and allow for some relief for a week or two, so that they don’t have to risk going to a crowded supermarket,” Parrish said.

Instead of allowing invitations to determine her travel schedule, as she did before the pandemic, Parrish said she now travels “out of necessity” with presidential approval.

But expectations regarding making every interaction with her people a positive one haven’t changed.

“It’s important to keep a balance and positivity whenever I get to interact with them, because what if they had a really bad day and somebody is dealing with domestic violence, or somebody is not getting paid and they need food?” she said.

“I need to leave that positive impression to ensure that they know that they’re loved, that they’re cared about and their lives are important.”

‘Not just something glamorous’

Parrish’s efforts moved rug weaver Marie Nez-Gamble to make a sash for Parrish, to show her family’s appreciation for “the amazing things she does and has done and will continue to do for our community.”

The sash took Nez-Gamble 36 hours to weave.

“She just really inspired us and just really didn’t hold back,” Nez-Gamble said of Parrish. “She educates young and old, encouraging them to continue their education, continue to speak their native language and learning their native culture.”

Crystal Littleben, who was Miss Navajo Nation in 2017-18, also praised Parrish for “putting herself out there” during a dangerous time.

Littleben, who already lost relatives to COVID-19, said she couldn’t assist her community the way she wanted to because she’d never forgive herself if she brought the virus home.

“It’s a hard task to take on,” Littleben said. Parrish “knows all those risks, and she probably has to distance herself from her own family just so that she can help her community that way.”

Shirley said Parrish has shown the title is a real service job, “not just something glamorous.”

“When she came to my community, there were a lot of the elderly that were happy to see her in her Navajo traditional attire handing out things,” Shirley said. “They were looking at her as a glimmer of hope, and they were saying, ‘We’re going to be OK. We’re going to be OK.’”

Parrish acknowledged the mental and emotional toll the pandemic relief efforts had taken on her, but she has no plans to step back.

Her latest aid project has the ambitious goal of ensuring that all 173,000-plus Navajos living on the reservation have five face masks each – and she’s sewing many of them herself.

“I know that our people need to see our leadership taking this on,” Parrish said. “I’ve really had to set aside my own emotions, my own thoughts, my own opinions about anything and everything that’s going on around me.

“The well-being of our people comes first.”

This story is made possible through a partnership between the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict at Arizona State University, with the support of the Henry Luce Foundation.