Wednesday, October 31, 2018

Every walker is provided with sample emails, a personal fundraising page and staff to provide guidance and fundraising (online or through mail) support.

Walkers who raise $100 or more will receive the National Walk Shirt. Walkers who raise $250 or more will receive additional fundraising prizes. The National Silver Sponsor is Salix Pharmaceuticals and the National Partner is CVS Specialty who help by offering product discounts to participants, providing product donations to the event and financial support.

The event features activities for kids, food, entertainment and information about the American Liver Foundation.

More than 10,000 people from across the country come together and raise almost $2 million annually. The event is free, but registration is required either before the event or at the event and there is no fundraising requirement, but walkers are strongly encouraged to raise a minimum of $100.

Form a team of family members, friends or colleagues and walk and fundraise together to make a difference in the fight against liver disease!

Liver Life Walk will take place on Saturday, Nov. 3 at Brandi Fenton Memorial Park from 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. Registration begins at 8:30 a.m.

5 Facts about the American Liver Foundation:

1. Their education programs reached approximately 46,000 people in 2016.

2. They are the leading source of information on liver health and liver disease.

3. Their toll-free National Helpline and 16 divisions across the country provide support to patients, families, caregivers and the public by phone, email and community outreach.

4. Their National Helpline volume doubled in 2016 with nearly 12,000 inquiries.

5. They have provided almost $26 million in research funding to over 840 early career investigators.

Tags: liver , life , walk , awareness , raise , money , disease , liver disease , food , kids , entertainment , information , fundraising , American Liver Foundation , Liver Life Walk , Image

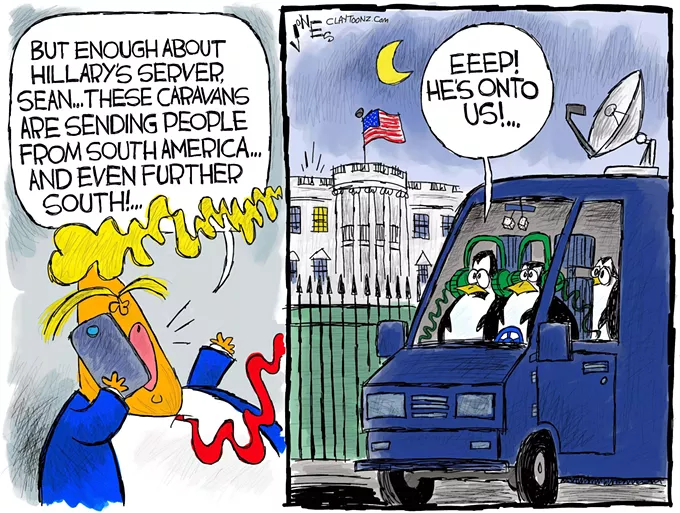

The motel is plain vanilla. Motorists streak past it on Interstate 10 without notice or memory. But inside the gates of the complex, over several days in October, 112 migrants, many from Guatemala, turned the motel into a temporary neighborhood.

Children chased their friends underneath the stairs. Parents leaned against walls and chatted with neighbors on a common path of pursuing asylum in the United States. The low hum of Spanish wafted through the rooms and grounds of the motel, mixed with English and peppered with phrases in indigenous languages, such as K’iche’ and Mam.

Inside, a first-floor office was packed with volunteers. On the walls, whiteboards and sticky notes that form a tracking system to help provide the migrants with food and shelter.

Upstairs, Elias sat on a polyester bedspread. He spoke of fear and relief.

Of bringing his child thousands of miles from home.

Of eluding police and gangs traveling through Mexico.

Of immigration authorities dropping him and his son and dozens of other migrants at the motel.

The migrants, who were fleeing poverty and crime in Central America, were allowed conditional entry into the U.S. after crossing the southern border and requesting asylum. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, with a spokesperson later saying there were too many migrants to handle, brought them to volunteers in Tucson who put them up at the motel on I-10.

Within a few days, the migrants scattered throughout the country.

But their stop in Tucson lingered in the continuing debate over immigration, both legal and illegal, in the U.S. and the rest of the world, among politicians, advocates and people across the ideological spectrum.

The migrants’ journey turned on the decisions of outside forces: Whether ICE would detain them or release them sooner to their destinations. Whether supporters would house and feed them or the migrants would be left to fend for themselves on the streets of Tucson. And, finally whether federal officials will ultimately allow them to stay in the U.S. or return them to the countries they fled.

The 112 Central Americans were among thousands seeking asylum in the U.S. According to TRAC Immigration, a nonpartisan immigration research program, from 2011 to 2016, 8,540 migrants applied for asylum to the federal government. Few, however, succeeded.

Tags: motel , Tucson , immigration , migrants , families , asylum , Image

The Equality Tour is coming to Tucson. The event is organized by Equal Means Equal, a charitable organization of the Heroica Foundation. The Equality Tour will feature speakers and comedic and musical performances all in support of passing the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

The Equal Rights Amendment is a proposed amendment to the U.S Constitution that would guarantee equal rights to both men and women, which would work to eliminate gender pay gaps.

So far, 37 of the 38 states needed to amend the U.S Constitution to include women have voted to ratify, with Nevada and Illinois voting yes in just the past year and a half. Arizona has the potential to be a history-making state because the amendment will only be passed if one more state ratifies.

Speakers at the event will include Kamala Lopez, the executive director of Equal Means Equal, Pamela Powers, Arizona State Representative of District 9, Victoria Steele, candidate for Arizona State Representative District 9, Athena Salman, Arizona State Senator of District 26 and Natalie White, Co-Director of Equal Means Equal and Feminist Artist.

The musical performance is Voices for Change (VFC), a community organization that brings awareness to important social and political issues through music. Soloists will include Ali Handal, Jason Chu and Anthony Fedorov.

Also at the event will be Nobody's Funny, a team of stand-up comics. Performing comics include Samantha Baxley, Buffy Metler, Eugenia Kuzmin, Joel Marshall, Or Mash and Jessica Winther.

The free event will be on Thursday, Nov. 1 at 6:30 p.m. and will be located at the MSA Annex Festival Grounds near the Mercado at 267 S. Avenida Del Convento.

To purchase free tickets for admission or for more information about Equal Means Equal, visit: http://equalmeansequal.org/

Empowerment Scholarship Accounts (aka Education Savings Accounts, aka Vouchers on Steroids) are a backdoor voucher program which gives debit cards to parents to spend on their children's educations so long as the children don't attend a district or charter school. When parents get the money, they're told it can only be spent on education. "We'll be watching you, so don't use the money for other things," they're told. But actually, no one is watching.

In fiscal year 2018, $700,000 was misspent by ESA parents according to an audit released by the Department of Education. The items include obviously non-educational purchases like beauty supplies, sports apparel and computer tech support. Very little of that money has been paid back to the state.

It's the kind of story the "good government" folks at the Goldwater Institute might want to cover. I say that because G.I. recently published a report on fraud in school districts. The report came fast on the heels of the Republic stories about people making millions on charters, so I'm guessing it was written to counter the bad press — G.I. loves charters almost as much as it loves vouchers — by saying, "Hey look, school districts do it too!" However, something tells me, pointing out voucher-related fraud isn't the kind of deflection G.I. is planning any time soon.

Tags: education , charters , vouchers , ESA , misspent , money , Image

The Halloween & Poltergeist Double Feature Terror-thon. Get spooky at The Loft this Halloween with their double feature Terror-thon. Halloween is up first, playing at 7 p.m. and Poltergeist follows at 8:50 p.m. If you aren't scared out of your seat, the best part about the whole event just might be the free candy for anyone in costume! So, don your spookiest garb and head over to The Loft to see the ghosts, ghouls and goblins of Tucson turn out to watch some of the best Halloween classics. Details here.

Ladies Night Out & Halloween Party at Cobra Arcade Bar. If you have every dreamed about playing your favorite arcade game dressed as your favorite arcade character, this is the event for you! Dress up in your best costumes for a night of game-filled fun. Doors open at 4 p.m. and it's happy our until 8 p.m. 63 E. Congress Street. Details here.

If you a are looking for something a little more kid-friendly and don't want to take the kids good old-fashioned trick-or-treating, there are a bunch of Trunk-Or-Treat events happening around town on Halloween evening. Check out the one at University City Church, the one at Urban City Tabernacle, the Halloween Bash at Pump it Up, or Spooky Toddler Storytime at the Eckstrom-Columbus Library.

Send Us Your Photos:

If you go to any of the events listed above, snap a quick pic and message it to us for a chance to be featured on our social media sites! Find us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @tucsonweekly.

Events compiled by Brianna Lewis, Emily Dieckman, B.S. Eliot, Ava Garcia and Jeff Gardner.

Tags: things to do , Tucson events , halloween , costumes , parties , trick-or-treat , scary movies , Image

Tuesday, October 30, 2018

It would be foolish of me to say with 100 percent certainty that the Arizona Supreme Court ruling against the "Invest in Education" initiative was politically motivated. I'm only 95 percent certain they wanted to knock the initiative off the ballot for political reasons — with a 5 percent margin of error.

The Supreme Court decision against Invest in Ed fits a little too neatly with the zero tolerance policy toward citizen initiatives enacted by the Republican majority legislature and signed by Governor Ducey to be a coincidence.

The legislature's zero policy law requires "strict compliance" with the rules governing petitions. Ridiculously strict compliance. If people carrying petitions make a mistake in the way they fill it out, no matter how small, the entire petition and all its signatures can be tossed. If people signing a petition go outside the lines with their signatures or other information — if the tail of a "g" or a "y" extends outside the line — that signature can be thrown out.

Why the new ridiculously strict compliance law? Because Republicans hate citizen initiatives. They'll do whatever they can do to make it harder for them to make it to the ballot.

It's easy to understand why. This year a citizen initiative limiting one of Republicans' pet projects, private school vouchers, is on the ballot. So is an initiative to increase the use of clean energy, something Republicans all over the country oppose so deeply, they've decided to ignore science, thermometers and their own eyes and say, "Climate change? What climate change?"

Then there are the two citizen initiatives that didn't make it. One would have banned Dark Money, the lifeblood running through the veins of Republican politics. The other is Invest in Ed, which would have made people whose taxable income is over $250,000 ($500,000 for couples) pay a higher income tax rate.

That's four initiatives Republicans despise. They never would let ideas like those get anywhere near the floor of the legislature, and they hate it that citizens have the ability to go around the Republican political stranglehold on the state by using the initiative process.

Tags: Citizen initiatives , Arizona Supreme Court , Invest in Ed , Strict Compliance , Image

Halloween Event at The Fox. Join the ghosts and ghouls at The Fox Theatre for their spooky Halloween event including the original Halloween Film (1978). This year marks the 40th anniversary of the classic horror movie starring Donald Pleasence, Jaime Lee Curtis and Tony Moran. To make a whole evening out of the show, join events in the lobby from 6 to 7 p.m. The movie starts at 7:30 p.m. For those who really want to keep the fun going, there will be a Ghost Hunt at 9:30 p.m. to midnight where you can hunt ghosts in the dark and empty Fox Theatre armed with paranormal hunting equipment. Tickets for the film are $5, tickets for the Ghost Hunt are $25. Pick your poison! 17 W Congress St. Details here.

Sugar Skulls Decorating. We are officially in the season where one holiday seems to lead right into the next, so if you are done with Halloween and can't wait for Día de los Muertos to roll around, this is the event for you! Decorate your very own sugar skull with sequins, feathers, glitter and more at the Quincie Douglas Library. All supplies will be provided, but the event is first come first served. 1585 E. 36 Street. 3:30-5:30 pm. Free. Details here.

Lowe's Food Truck Roundup. There is some sacred unwritten rule that says food from a truck is delicious, it's just a rule. Well today you are in luck because a whole bunch of food trucks are going to park up in one spot for one yummy traffic jam. Food trucks in attendance will include Meatball Madness, Haus of Brats, Nhu Lan Vietnamese Food and Don Pedro's Peruvian Bistro. The event runs from 5-8 p.m. at 4075 W Ina Rd. Details here.

Send Us Your Photos:

If you go to any of the events listed above, snap a quick pic and message it to us for a chance to be featured on our social media sites! Find us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram @tucsonweekly.

Events compiled by Brianna Lewis, Emily Dieckman, B.S. Eliot, Ava Garcia and Jeff Gardner.

Tags: things to do , events , halloween , family , friends , sugar skulls , ghosts , miniatures , Image

Monday, October 29, 2018

What more can you say about a handsome guy like Tadmore? This big boy is still just a pup at 1-year-old and he's got the personality to prove it! He's lovable and kinda goofy, but he's also super-smart.

Best of all, he's brimming with energy and loves to play. His forever family will want to be an active one, and what better way to get to know Tadmore after you adopt him than by taking him for a walk?

Meet Tadmore at HSSA Main Campus at 635 W. Roger Rd.For more information give an adoptions counselor a call at 520-327-6088, ext. 173.

Tags: adoptable pet , Tadmore , dog , pet , family , home , puppy , adopt , Image