Thursday, August 9, 2018

University of Virginia Needs To Pay Back By Paying Forward

The University of Virginia, founded by Thomas Jefferson and opened in 1825, owes a debt to people who were forced to build the university, then maintain it and feed and care for the professors and students, people who were treated as property belonging to their "owners." UVA has made a first step in acknowledging the slaves whose labor built and maintained the university, but it has done little to repay the debt it owes them.

Here's my suggestion to UVA: Pay back by paying forward.

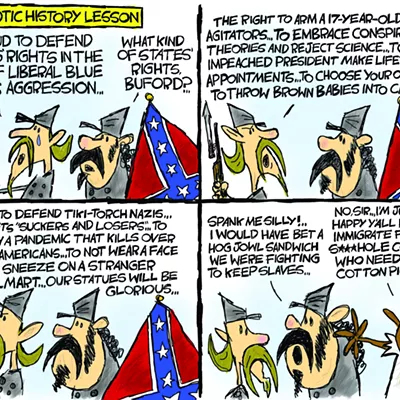

The racism of the Unite the Right participants is well known. The history of slavery at UVA, however, like the history of slavery in the U.S., is clouded by our national determination to paint our country's original sin in broad strokes and ignore its disturbing details. The UVA report is one of the recent attempts to bring the full, accurate history of slavery to light.

Based on the commission report, it's fair to call UVA the university that slavery built. According to the report, "Slavery, in every way imaginable, was central to the project of designing, funding, building, and maintaining the school."

The dollar value of the slave labor which directly contributed to the building and maintenance of the university is only one part of the story. The people who funded the building of the school were Virginians who owed their wealth to the state's slave-based economy, including the country's third, fourth and fifth presidents, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe.

The mission of the university was to become Virginia's answer to Harvard University. That didn't simply mean creating a prestigious intellectual center in the state. It also meant protecting and preserving Virginia's system of slavery.

Thomas Jefferson made that mission explicit in a letter to a friend.

UVA was built on the backs of slaves and it continued to do harm to the descendants of slaves throughout its history. Today, African Americans make up 20 percent of Virginia's population but only 6.1 percent of UVA's undergraduates. While the Slavery and the University Commission report is an important document, it doesn't suggest that UVA is making a major effort to right its historic wrongs. The university has begun to recognize its slave history with placards, recreations of old buildings and walking tours. It offers modest scholarship opportunities to African Americans. That isn't enough.

I believe a more active program should be enacted at UVA. The university already has a Legacy program to help children of alumni with the admissions process. While it doesn't guarantee acceptance, it offers information sessions and personal meetings with the families which begin as early as the potential students' freshman year in high school. The same opportunities, and more, should be extended to Virginia's African American students, or any students around the country who can trace their ancestry to Virginia's slave population. UVA should offer a full range of counseling, tutoring and mentoring programs to those students who express interest in attending the university, beginning in high school or earlier. Those who are accepted to the university should be given full ride scholarships as well as a continuation of counseling, tutoring and mentoring services they received as K-12 students.

All that takes money, but UVA should think of it more as a late repayment of an outstanding debt than an added expense. Historians, economists and mathematicians can work together to figure out how many slaves worked at the university and the monetary value of their labor in today's dollars, with the understanding that some of them were skilled artisans and craftspeople whose work was highly valued. If they want to take a more cautious approach and consider only the value added by slave labor, they can compare the cost of slave labor to the cost of hiring free people to do the same work. The difference would set a base amount for an endowment of the program.

The university should also add other considerations to their figurings, like interest accrued over the years, the value of the freedom which was denied to the slaves and the percentage of the money donated to the college which is directly attributable to the slave-based economy. However the final amount is determined, the endowment would allow UVA to cover the cost of tuition and expenses for descendants of Virginia slaves who decide to attend the university, people whose ancestors were forced to build and maintain an institution which benefitted white Virginians but brought them only hardship and oppression.

Here's my suggestion to UVA: Pay back by paying forward.

• Extend the meaning of "legacy student" from the children of UVA alumni to include the descendants of slaves who were forced to build and maintain the school.The first anniversary of the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, home of UVA, comes in a few days. Coinciding with the anniversary is the publication of the final report of the UVA's Slavery and the University Commission, which began its work in 2013. Together, the two events put the issues of pre-Civil War slavery and present-day racism into stark perspective.

• Create a UVA fund dedicated to the educations of their descendants based on the monetary value of their ancestors' contribution to the university.

The racism of the Unite the Right participants is well known. The history of slavery at UVA, however, like the history of slavery in the U.S., is clouded by our national determination to paint our country's original sin in broad strokes and ignore its disturbing details. The UVA report is one of the recent attempts to bring the full, accurate history of slavery to light.

Based on the commission report, it's fair to call UVA the university that slavery built. According to the report, "Slavery, in every way imaginable, was central to the project of designing, funding, building, and maintaining the school."

The dollar value of the slave labor which directly contributed to the building and maintenance of the university is only one part of the story. The people who funded the building of the school were Virginians who owed their wealth to the state's slave-based economy, including the country's third, fourth and fifth presidents, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe.

The mission of the university was to become Virginia's answer to Harvard University. That didn't simply mean creating a prestigious intellectual center in the state. It also meant protecting and preserving Virginia's system of slavery.

Thomas Jefferson made that mission explicit in a letter to a friend.

Even in Jefferson’s own imagining of what the University of Virginia could be, he understood it to be an institution with slavery at its core. He believed that a southern institution was necessary to protect the sons of the South from abolitionist teachings in the North. Jefferson wrote his friend James Breckenridge in 1821, expressing his concern with sending the youth of Virginia to be educated in the North, a place “against us in position and principle.” He worried that in northern institutions, young Virginians might imbibe “opinions and principles in discord with those of their own country. This canker is eating on the vitals of our existence, and if not arrested at once will be beyond remedy.”The university was "an incubator for pro-slavery thought," according to the report, which says its racist mission extended beyond the Civil War.

[UVA] had become the intellectual protector of white supremacy and of the idea that slavery should be perpetual. Those messages were spread across the country by alumni who became lawyers, judges, university professors, doctors, and legislators elsewhere. This heritage would not disappear after Confederate defeat in 1865. It would not end in March 1865 when Union General Sheridan’s forces occupied Charlottesville and effectively freed 14,000 Albemarle residents. It would not disappear with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment officially abolishing slavery. It would not disappear with the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments seeking to create and protect African American citizenship. It was still with us in the early twentieth century when UVA became a eugenics center, it was still with us in the 1920s when the University had its own Ku Klux Klan chapter, and it appeared as recently as 2001 when the University objected to a state historical marker on University property that recounted Charlottesville’s surrender to Union forces in 1865.In 1950, 125 years after its opening, UVA admitted its first black student. He was a Howard College graduate who was already practicing law. The school didn't begin accepting black students in earnest until 1955, after the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

UVA was built on the backs of slaves and it continued to do harm to the descendants of slaves throughout its history. Today, African Americans make up 20 percent of Virginia's population but only 6.1 percent of UVA's undergraduates. While the Slavery and the University Commission report is an important document, it doesn't suggest that UVA is making a major effort to right its historic wrongs. The university has begun to recognize its slave history with placards, recreations of old buildings and walking tours. It offers modest scholarship opportunities to African Americans. That isn't enough.

I believe a more active program should be enacted at UVA. The university already has a Legacy program to help children of alumni with the admissions process. While it doesn't guarantee acceptance, it offers information sessions and personal meetings with the families which begin as early as the potential students' freshman year in high school. The same opportunities, and more, should be extended to Virginia's African American students, or any students around the country who can trace their ancestry to Virginia's slave population. UVA should offer a full range of counseling, tutoring and mentoring programs to those students who express interest in attending the university, beginning in high school or earlier. Those who are accepted to the university should be given full ride scholarships as well as a continuation of counseling, tutoring and mentoring services they received as K-12 students.

All that takes money, but UVA should think of it more as a late repayment of an outstanding debt than an added expense. Historians, economists and mathematicians can work together to figure out how many slaves worked at the university and the monetary value of their labor in today's dollars, with the understanding that some of them were skilled artisans and craftspeople whose work was highly valued. If they want to take a more cautious approach and consider only the value added by slave labor, they can compare the cost of slave labor to the cost of hiring free people to do the same work. The difference would set a base amount for an endowment of the program.

The university should also add other considerations to their figurings, like interest accrued over the years, the value of the freedom which was denied to the slaves and the percentage of the money donated to the college which is directly attributable to the slave-based economy. However the final amount is determined, the endowment would allow UVA to cover the cost of tuition and expenses for descendants of Virginia slaves who decide to attend the university, people whose ancestors were forced to build and maintain an institution which benefitted white Virginians but brought them only hardship and oppression.

Tags: University of Virginia , Slavery and the University Commission , Slavery , Unite the Right , Thomas Jefferson , Reparations , Image