Monday, October 24, 2016

Be a Voter! (Then Vote)

One of the things I read as a young teacher which stuck with me was, be careful of your use of the verb "to be" when reprimanding a student. If a student lied to you, don't say, "You are a liar." Say something more like, "You told a lie." If a student cheated, don't say, "You are a cheater." Say something more like, "You cheated on that last test." If a student regularly disrupts class, don't say, "You are nothing but a troublemaker." Say, "I won't let you continue to disrupt class," or, "If you keep causing trouble in here, I will . . ."

The reason is, the statement "You are . . ." is very powerful. It is a statement of being, referring to your essential nature (I just checked to see where the word "essential" comes from. It's from the Latin "esse," "to be.") So if I say to a student, "You are a liar," I'm saying that lying is an essential part who that student is. If, on the other hand, I call a statement a lie, I'm dealing with one specific statement at one moment in that student's life, which means the student has the opportunity to stop lying by making a change in behavior, which is far easier than changing his or her essential nature.

It's probable that the other side of the "to be" coin is true as well: if you can get someone to identify with a positive trait by saying, "I am a . . .," you can increase the chance of that person acting on it.

I read a short piece recently that said people are more likely to vote if they consider themselves "voters," as in, "I am a voter," than if they say, "I vote." It cited a study indicating that people who accept the label of "voter" are more likely to cast their ballots than people who simply say they vote. It makes sense to me. If you think of yourself as a "bowler"—"Yeah, I'm a bowler"—you're more likely to hit the lanes than if you say, "Yeah, I bowl now and then." Bowling is part of something you are, not just something you choose to do when the mood strikes, when you have some spare time.

Bowlers bowl. Voters vote.

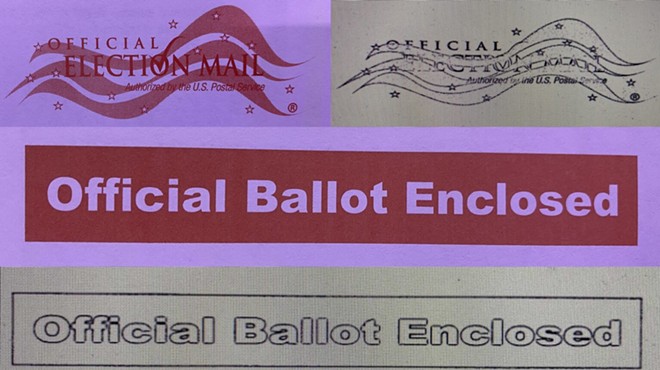

So I say, let's all be voters, people who act on that essential part of our being whenever the opportunity arises, which happens to be between now and Nov. 8—or a few days earlier if you mail in your ballot.

An Emerson Erudition Extra: Ralph Waldo Emerson touched on the idea of our state of being—who we are—in his essay, The American Scholar. He bemoaned the fact that too many people consider their occupation to be their essence. A "Farmer," Emerson wrote, should instead consider himself "Man on the farm." A "Scholar" shouldn't say, "I am a scholar." He should think of himself as "Man thinking." That way, we reclaim our essential humanity, the sense that we are all part of a whole, rather than dividing ourselves from one another by our chosen occupations. "The state of society is one in which the members have suffered amputation from the trunk, and strut about so many walking monsters,—a good finger, a neck, a stomach, an elbow, but never a man."

Here's the extended passage. Even if you were turned off to Emerson by being introduced to him too early or too forcefully—and, worse, being tested on what he wrote—you might give this a look, though you may have to get past the fact that he uses the male form, Man, to talk about humanity. This guy could write a hell of a sentence, and a paragraph, and an essay.

It is one of those fables, which, out of an unknown antiquity, convey an unlooked-for wisdom, that the gods, in the beginning, divided Man into men, that he might be more helpful to himself; just as the hand was divided into fingers, the better to answer its end.

The old fable covers a doctrine ever new and sublime; that there is One Man, — present to all particular men only partially, or through one faculty; and that you must take the whole society to find the whole man. Man is not a farmer, or a professor, or an engineer, but he is all. Man is priest, and scholar, and statesman, and producer, and soldier. In the divided or social state, these functions are parcelled out to individuals, each of whom aims to do his stint of the joint work, whilst each other performs his. The fable implies, that the individual, to possess himself, must sometimes return from his own labor to embrace all the other laborers. But unfortunately, this original unit, this fountain of power, has been so distributed to multitudes, has been so minutely subdivided and peddled out, that it is spilled into drops, and cannot be gathered. The state of society is one in which the members have suffered amputation from the trunk, and strut about so many walking monsters, — a good finger, a neck, a stomach, an elbow, but never a man.

Man is thus metamorphosed into a thing, into many things. The planter, who is Man sent out into the field to gather food, is seldom cheered by any idea of the true dignity of his ministry. He sees his bushel and his cart, and nothing beyond, and sinks into the farmer, instead of Man on the farm. The tradesman scarcely ever gives an ideal worth to his work, but is ridden by the routine of his craft, and the soul is subject to dollars. The priest becomes a form; the attorney, a statute-book; the mechanic, a machine; the sailor, a rope of a ship.

In this distribution of functions, the scholar is the delegated intellect. In the right state, he is, Man Thinking. In the degenerate state, when the victim of society, he tends to become a mere thinker, or, still worse, the parrot of other men's thinking.

Tags: Voter , Voting , Ralph Waldo Emerson