Friday, July 11, 2014

Education Leaders And Top Democrats Part Company

Last week, the National Education Association held its annual convention. Biggest news: they passed a resolution asking Arne Duncan, Obama's Secretary of Education, to resign. Second biggest news: the NEA's new president is Lily Eskelsen Garcia — she began as a cafeteria worker and went on to become Utah's Teacher of the Year — who promises to promote a more assertive, activist agenda than the NEA has employed in the past. It has generally been the smaller teachers union, the American Federation of Teachers, that has been the firebrand while the NEA tried to steer a more moderate, middle ground. It's looking like the NEA wants to get in the fight.

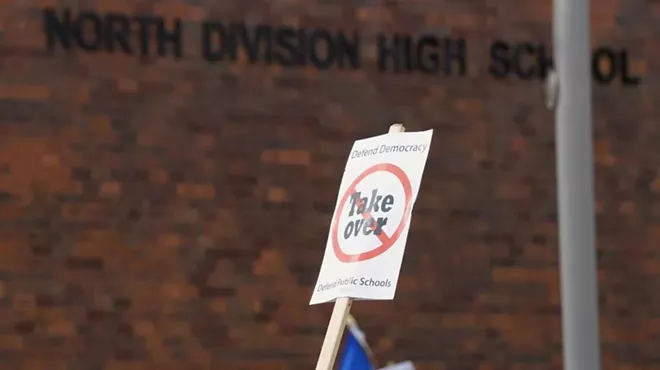

This is the latest skirmish in the growing battles over the best ways to improve our children's educations. By naming Arne Duncan Secretary of Education, Obama threw in with the more conservative "education reform" wing of the Democratic party, which has formed an uneasy alliance with conservatives and billionaires who spend millions of dollars trashing public schools and pushing a privatization agenda. That means focusing on high stakes testing and charter schools and harping on problems in traditional public schools — painting the schools and the teachers who work in them as failures. The teachers unions, along with many educators and progressives, disagree. For the NEA, which tends to put its money and influence behind Democrats, to officially call for Duncan's resignation indicates how wide the divide has grown.

The education controversy raging in the country has lots of moving parts. Whole books have been written about the battles and the motivations of the actors in this drama. I want to concentrate on just one aspect of the controversy because it hasn't gotten as much attention as it deserves: the philosophical divide at the core of the discussion.

On one side, the more conservative education reform/privatization movement maintains that traditional public schools and teachers are to blame for our students' poor achievement and, by extension, for problems like poverty and income inequality. Fix the schools and our social ills will take care of themselves, they maintain.

The other, more progressive side maintains that poverty, income inequality and lack of social and economic mobility are societal illnesses which are too deep seeded and pervasive to be cured by the schools. By blaming schools for some of our country's most troublesome structural problems, they say, we're aggravating and perpetuating a situation we should address head on. We need to couple aggressive measures addressing root causes of poverty with efforts to make our schools more effective, and the two will improve together.

Adopting either of the two narratives takes you in significantly different directions.

If the fault lies with our current public school systems and the teachers who work in them as the reform/privatization crowd asserts, then the solution is, Throw the bums out! We have to tear out the failing school system root and branch. That means creating a whole new type of school, the charter school, which will succeed because it operates outside the current system of failure, and maybe even sending kids to private schools on the public dime. It means closing "failing schools" or firing entire school staffs and starting over. It means coming up with a clear way to measure student success and failure — yearly standardized tests — and using the results to determine which schools and teachers stay, and which schools and teachers go.

And it also follows from this way of thinking that we can spend less on all those social programs that only make things worse by perpetuating a culture of dependency. If we just get kids into great schools with great teachers . . . problem solved.

But if schools aren't the prime mover in our social ills, which is what the progressive side of the education battle asserts, then a radical reform of our education system won't have the revolutionary effects the "school reformers" predict. All the shifting and shuffling and privatization will create schools which are marginally better or marginally worse than what we have now, but they won't have a serious impact on student achievement, poverty, income inequality or social and economic mobility. And the dismantling of our system of public schooling which, for all its flaws, is one of this country's great accomplishments, could leave us with schools that are even more segregated than they are now, greater educational inequality and a more fragmented society.

And, according to this argument, by misdirecting all our attention toward schools and ignoring the underlying social and economic causes, we're allowing some of our most serious problems to fester, which will result in losing another generation of children.

Anyone who has read my posts knows I'm on the more progressive side of this argument. A few months ago, I created a map of the letter grades of schools in the greater Tucson and Phoenix areas, and another map with the average income levels of families. The correlation between the A-F grades and income levels is astounding. The "A" schools are mainly in the high income areas, the "B" and "C" schools are in the middle class and transitional areas, and the "D" schools are concentrated in the areas of highest poverty. But that shouldn't surprise anyone, because no matter where you go in the world, you'll find a similar correlation between family income and student achievement. As poverty lessens, and with it the stresses and burdens poor children carry with them into school, student achievement increases. High stakes tests haven't changed that basic fact. Charter schools and private schools have the same mixed record of student achievement as school districts when you compare similar students. No one has discovered a reliable, reproduceable educational fix for the income-related achievement gap.

I join the NEA and a large part of the progressive community in wanting to see Arne Duncan go and a more progressively minded educator take his place. Obama should replace Duncan with someone more like Linda Darling Hammond, his education adviser during his 2008 presidential campaign. She, or someone like her, would create a better balance between the need to improve the lives of children outside of school as well as inside.

Tags: National Education Association , Arne Duncan , President Obama , Education privatization , Linda Darling Hammond