Cecilia Acevedo has come a long way since working 12-plus-hour shifts at the maquiladoras in Ímuris, Sonora.

She moved there from her hometown of Cananea—a mining city less than an hour away from Naco, Arizona—at the age of 15 to get a factory job. While working there, she met her husband, and 15 years after that, the couple immigrated to Tucson. They wanted their children to have better opportunities than the ones they ever got.

Acevedo remembers going to work at a ranch as early as 3 or 4 a.m., and bringing her youngest daughter, Belinda, along—wrapped in thick blankets during the winter, carefully tucked in a wheelbarrow. The couple's job was to feed horses and other farm animals. They were undocumented at the time.

"For a long time, we would just work, work, work," Acevedo says. "We never even knew Tucson because we were always locked up at the ranch."

After years of hustling, Acevedo's and her ex-husband's income was enough to rent a home big enough for the family of four. But then the divorce came and Acevedo's husband took off. "He just quit," Acevedo says. Her daughter was 10, and her son was 16. Her ex never paid child support.

Acevedo could no longer afford rent, so she and her two children moved into a tiny apartment in South Tucson. That's how it went—from small apartment to small apartment, trying to leverage a low income while trying to feed her kids and keep a roof over their heads.

Even after her son—who became a legal resident through marriage when he was still a teen—claimed Acevedo and helped her get a green card, it's been tough to get by with little English and no high school diploma.

About a year ago, though, Acevedo heard about a program sponsored by the Primavera Foundation, a nonprofit that focuses on helping the homeless community and people living in poverty.

The Her Family program focuses on economically empowering single mothers and their daughters—everything from teaching them how to best manage even the smallest of incomes to striving to become homeowners and providing a pathway out of poverty.

Two weeks before Christmas last year, Acevedo and her daughter moved into a brand new, three-bedroom, two-bathroom home in the City of South Tucson. She jokes that no one else wanted to move there because of the location. To her, it's all she ever wished for.

"There is a really high success rate. Having people support each other with their goals ... sometimes they might be in the program for several years, but many of them have become successful first-time homebuyers," says Peggy Hutchison, CEO of the Primavera Foundation.

Thanks to $30,000 raised by Primavera and several other partner organizations, Acevedo's mortgage woes went from $75,000 to roughly $44,000. She pays about $400 monthly—including utilities—which is a few hundred dollars less than what she paid when she rented.

Acevedo still works seven nights a week for a company that cleans banks afterhours. And, during the day, she does other housekeeping jobs. But at least now she can save up to go on vacation with her family—something that a few years back was unimaginable.

"I can't sit down, I have to work. My daughter tells me, 'Mom, don't go to work today, stay with me.' But I tell her ... working ... that's how I have accomplished this," she says as she sits on a couch she just bought for her home. Her daughter sits next to her, smiling and looking at photos from their recent trip to Kino Bay, Sonora.

Affordability and a Better Life

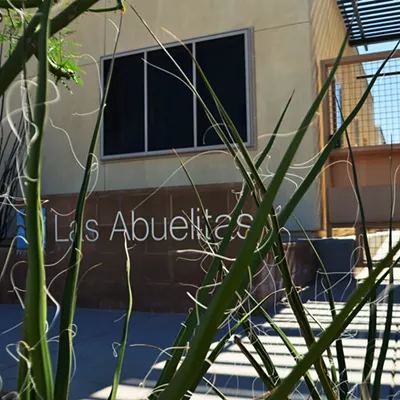

The Primavera Foundation runs a handful of services promoting affordable homeownership and rent for families and single mothers like Acevedo. It's also been the push behind housing projects like Las Abuelitas—low-income rentals for grandparents who are raising their grandchildren. In the case of Las Abuelitas, the land where it stands was donated by Pima County, and the apartments will remain low-income for three decades.

There's also transitional housing, which is primarily for people who are getting off the streets. But, for long, programs either via Pima County or organizations like Primavera and the South Tucson Housing Authority, have been there to benefit the working poor. Plenty in the City of South Tucson spend more than one-third of their income on rent and utilities—as was Acevedo's case in the past—or simply get by couch surfing.

As South Tucson struggles at every level, establishing a foundation for dignified living conditions is key to see the city improve economically.

"From our perspective, there is no equity of opportunities in our community and across this nation," Hutchison says. "Our role as an organization is to partner with them, providing that opportunity for people to build their assets. They are strong, they are smart, they work really hard, but not everybody has an equal play field. If you look at poverty ... women, families of color, working poor. They tend to be in that cycle [because] they don't have the same opportunities."

Housing Authority purely focuses on low-income rents—getting people back on their feet so they can move onto a better future. Under that umbrella, there are 50 family units—from one to four bedrooms—and 50 apartments for senior citizens and people with disabilities.

Despite the headaches of trying to maintain a facility like the Housing Authority, Executive Director Marilyn Chico is proud to be at the forefront of a place that makes a dent in people's hardships. Without the Housing Authority, which gets very limited funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, hundreds of people would either remain on the streets or living in decrepit apartments paycheck-to-paycheck.

"I look at the kids and say, 'Well, thank God I know you at least have a decent place to live in," she says. Chico has worked at the Housing Authority for 20 years. "Since I have been here, I am seeing second generation going into public housing. That part to me is heartbreaking. We are seeing the poorest of the poor."

But there are also the success stories—the young single mothers who, because of an affordable rent, could drop the second job to finish school, or save up for a down payment on an affordable home. "We have had young women who have gotten really good jobs, bought their own homes," Chico says. "We provide self-sufficiency to help people get into the job market and better themselves."

Relying on one source of funding—HUD—makes for an interesting rollercoaster. Whatever happens, though, Chico knows that low-income housing will always exist. However, she does wish that the City of South Tucson could count on extra money to invest in programs that benefit its residents. It's frustrating to her to have several minds who want to do so much for this little city but have their hands tied. There simply is no money.

"Everybody is always fighting for grants. Everybody is looking for money, looking for revenue to come in and help the programs so we can service the residents of South Tucson better," Chico says. "That is the goal for everyone here."

It's no news that South Tucson struggles—the same old but very accurate tale of the cycle of poverty and disenfranchisement experienced by the 80 percent of Latinos and Hispanics who live in the pueblo within a city.

In 2013, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco looked into the demographics of several Pima County towns and cities, including South Tucson— a 1.2-square-mile city that's home to at least 5,500 people.

The report found that 22 percent of the city's residents are unemployed, and those who do have a job have a median income of $22,000 a year. If you're a single mother, which 13 percent of South Tucson's households are, the figure may be less.

More than half of South Tucsonans live below the poverty line, and 84 percent of homes—even with one working family member, is on food stamps or some sort of government help. It's no coincidence that, simultaneously, fewer than 5 percent of South Tucson residents have a college degree, and roughly more than half have a high school diploma or GED—compared to areas like Catalina Foothills, where less than 10 percent of residents are Hispanic or Latino, the average income is $80,000 a year, and way more than half of residents have bachelor's degrees or higher.

Pima County and South Tucson are trying to promote homeownership in the city, a place where more than 70 percent of people rent. But without affordable options, it's unrealistic to expect a person making $20,000 annually will even consider jumping into that route.

The deep-rooted issues only seem to get worse when there's a local government that is drowning in deficit. With a budget in fiscal year 2015-16 of about $10 million, debt piles up—from the $300,000 the city owed Waste Management, which left the thousands of residents without garbage service starting in August of last year (South Tucson recently reached an agreement with the City of Tucson for the latter to absorb trash services in its sister city), to the roughly $1 million the city owns in jail bills to Pima County.

"Housing is one of our biggest infrastructure problems. There aren't many options for improving housing and for creating affordable housing," says Mick Jensen, a planner with the City of South Tucson. Every now and then, the city gets HUD money through Pima County. But that funding has gone from about $400,000 to $60,000—and it's all been geared toward emergency home repairs, he adds. "We used to have a limit of $25,000, so that's two houses. We have done emergency home repairing with a limit of $8,000, but once again that's seven or eight houses that you can do some repair to. There isn't much money out there."

To pile up to the laundry list of disadvantages, there's a pattern in South Tucson of property owners who are MIA, merely collecting rent money for properties they don't even maintain.

"The housing situation makes our crime problems more difficult, too" Jensen says. "What you really would hope is that landlords would be more aggressive in taking care of their properties. Absentee landlords, who are willing to rent to people without background information ... that invites all sorts of bad behavior."

In May 2015, South Tucson's Planning and Zoning Department presented an economic development plan that proposed to redevelop 37 acres of empty land and unused property, and morph it into a business center to generate more jobs, as well as property and sales tax. It's all with the hope to hike the city's revenue and get out of debt.

Planning and Zoning Director Joel Gastelum says the city would offer incentives to business and property owners, such as an eight-year property tax abatement.

But before this plan rolls out, the city has to persuade the yet unidentified people behind the acres and acres of undeveloped buildings and land.

Betty Villegas, program manager at the Pima County Housing Center, calls them slumlords. They, too, have been a major block in efforts to develop affordable housing in South Tucson.

There's the Pima County Community Land Trust, which relies on landlords' willingness to sell at an affordable price, or donate altogether, their land or establishment so that it can be "rehabbed" and then sold to low-income buyers.

The whole purpose of a community land trust is to provide residents the opportunity of owning a home for cheap—but the land remains property of the county or city.

"The home stays affordable for the long term. It is a 99-year lease," says Maggie Amado-Tellez, executive director of Pima County Community Land Trust, meaning a mom could pass down the house to her daughter, without concerns of whether or not it can be afforded in the future.

"Home ownership is probably the biggest investment that most people of color will make. People want to own a home because they want to give their families security and safety," Villegas says.

Amado-Tellez says that, sadly, there hasn't been much progress in the program. The city doesn't have any money to invest in it, or properties to donate, and the county has to stretch the fund it gets from HUD among all of its incorporated and unincorporated areas.

As of now, Amado-Tellez, and other collaborators, are trying to build up a list of abandoned properties, "contact the owners and see if they are willing to sell to us or give them to us," Amado-Tellez says.

Women who go through Primavera's Her Family program also learn about the land trust model. As Acevedo puts it, it's not about the location of the home, or owning the land, it's about what's inside and having the satisfaction of decorating a home that's yours for the long run.

But, just like the county, hunting for property owners is a big challenge.

"The city has a hard time locating the owners, [but] we can work together," Hutchinson says. "It is also about keeping neighborhoods safe. Having healthy and affordable places to live."

Part of building strong neighborhoods and cities is having more homeowners and people who care about improving their surroundings, Jensen says.

Despite criticism and ongoing propaganda that South Tucson should become part of the City of Tucson, Gastelum and Jensen have no doubt that South Tucson will see better days. They have faith in the economic development plan, which they see as the key that will open the door to other types of growth, including improved housing.

"At times it discourages us, [but] I am not going to let it put us down," Gastelum says. "We still have to move forward and a lot of things are happening. The biggest thing is making South Tucson a destination point. Once we do a lot of things we want to get done here, I hope they will see how important we are and what a big asset to the overall community we are."

Like many areas in Tucson, Gastelum and Jensen fear progress in South Tucson will come with gentrification. So, it's very important for city officials to foster growth but take care of what's kept the city's soul afloat—its history and culture.

"South Tucson is one of the last neighborhoods that hasn't been invaded ...taken over by outsiders coming in, buying property and improving it to the extent that it is not affordable to most people here, so [residents] lose their housing options," Jensen says. "There are good and bad news to gentrification. It obviously improves property, brings up the general demographic of the neighborhood, high-income people. What we would like to do is protect the folks who live here."

"The cultural strength here is our biggest asset. I think that people don't often look at the good that is South Tucson...yes, we have money problems right now, but every municipality has money problems," Jensen adds. "Nobody in South Tucson thinks we should fold up and go away. The people in South Tucson are very protective of the city as an entity. We certainly can't feel any different than that."