The instrument maker strikes a key near the middle C, lets it fade and hits the next note up. His eyes, which merit mention because they are extraordinarily disarming and blue, widen, and he says, "the piano is evil! There are 12 notes between the two you just heard and we don't get them."

He's all too sweaty. It's a monsoony day so his swampbox is useless, yet his energy flows. One of his 25 self-released albums hums at low volume in another room of the house, its deep rhythms and sonic loveliness just audile.

"We only get 88 notes on the piano," he continues. "Humans can hear like 1400 notes in this range. It's evil! It takes all the nuance out of music."

So there's little musical beauty in this wooden box that's been around for more than 300 years?

"Oh, no!" he clarifies. "I'll listen to Chopin and Debussy and Satie, all day sometimes. Great shit. People do amazing things with these tools. But the idea that the piano limits our world is terrible thing."

The ensuing conversation twists and bends and the chain-smoking instrument maker rapid-fires theories about turning stagnation to stimulation, cultural prejudice and hegemony to revolt and forward movement, quoting and citing everyone from Clash man Joe Strummer to French theorist Michel Foucault to Coltrane and Mingus and his own mother ("the other suburban mothers called her 'a commie'," he adds).

He extols virtues of Middle Eastern and Chinese folk music, and even brainy mid-20th century Euro composers Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, and he really lights up when talk returns to tired traditions in Western music, from classical to contemporary pop. Without yoking conversation with music theory gobbledygook he waves his hands and rails against Bach and Beethoven, and old white hippies playing blues in Santa Fe bars, and ...

"This is what's sad to me. I've always listened to music from all over the world. Today if you play me something new from Mali or Brooklyn I can't tell the difference. It's the same syntho-pop sound, the same this and that. Every now and then somebody from a town far enough away, like Tinariwen [Grammy winners from Algeria] arrive and they sounded really different — desert and Arabic — but by the fourth album they sounded like a rock band. You know, producers get ahold of them, saying shit like, 'just put a little bass in here.'

"Worse than that," he continues, "there's this embedded imperialist concept in Western music, and I go all conspiracy theorist on this shit, which I don't normally do. The idea of having everything the same is so very Western. It goes back to Plato and it runs through the Catholic Church, and that's who decided our Western musical system. It's in Plato's Republic; it says, 'we will only have two modes, the mode that is triumphant and the mode that is humble!' And all fucking Western music—at least until Stravinsky shook it up—is right in those two things."

He's right, of course. And Igor Stravinsky was pretty punk rock when he, on the eve of World War One, debuted "Rite of Spring," an orchestral stunner of such savaged romanticism and groundbreaking polyrhythms it changed music. Stravinsky, along with Strummer, Foucault, Coltrane, Mingus, and his own mother, are but a few of this guy's heroes, which makes sense when you listen to his music and the mad, virtue-signaling instruments he invents.

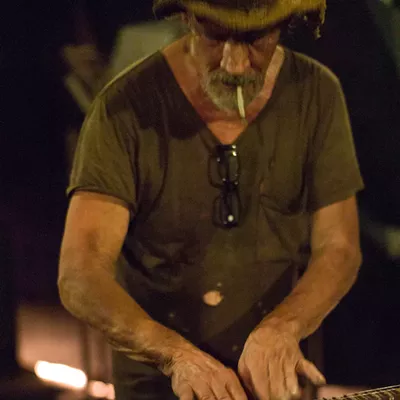

This is Andy Thurlow, a multi-instrumentalist any shortsighted observer might dismiss as an art-damaged hippie/punk acid casualty: A dirt-colored T and frayed jeans cling to his lithe frame. A pinch-front straw hat sits on graying Jesus hair, shading an elements-carved face. But he's hardly toast. He's particular, unabashedly himself at all times, and an eloquent autodidactic, a high school dropout who left his suburban Jersey home young. There's unjaded sweetness about him too; he listens hard, queries me as often as I him, and derails compliments with droll self-putdowns.

Thurlow lives alone on a spectacular mesquite-shaded compound of sorts in Barrio San Antonio. His rented house is surrounded by ramshackle workshops, some of which he erected himself to build and house his instruments. There are anvils, forges and welding stations, scrapheaps and an electrical workshop. There's a shack-turned-photo-studio, and up some steps a lookout patio. He calls his place "The Vine."

He steps into a dusty pentagon-shaped room filled with his one-of-a-kind instruments. Second shortsighted impression: this is the breathtaking work of an absolute madman.

His instruments are gallery-worthy, sonically and visually; 19th century industrial meets ancient folk instrumentation and punk-rock DIY frugality, and lots of childlike whimsy. Some creations recall instrument maker Harry Partch (who also composed), but are far more Road Warrior-esque. Some have familiar tones, but many do not, and there's a wealth in textures and tunings. All reflect the man's life, world and philosophies.

Adult-tall stringed things stand next to steel-barred xylophones next to squat drums with goatskin and leather heads, and science-fiction springed noise makers. There are pitched domes (like bells) of different sizes fashioned from found objects like helium tank bottoms and old compressors, some hang above a tone-changing tub of water. There are suspended barrels, cymbals and kalimbas. Most instruments have funny names like King Lyre and Farp, and they demand more than mere attention; they demand participation.

Thurlow flips on the PA (many of his instruments, even the percussion, are electric, fitted with Thurlow's homemade pickups) and like some snake charmer he plucks and taps and spins things, producing heavy hums and hushed tones, otherworldly sounds and melodies in beds of harmonics and distortions.

One free-standing (nearly 6-feet) instrument called the "Hendecq" sees heavy-wound strings that angle out, attached with guitar tuners, and a movable bridge so you can tune the instrument higher or lower. When you pluck the strings it drones sitar-like and you can bend each string's pitch with your other hand and fingers.

There's a fantastic cubist-looking thing called "Ena" that'd eat up a corner of a sizable room and it features banks of strings at different heights and creates a heavy, tooth-resonating chorus effect. His "cuth" sees wound piano strings stretched over an old satellite dish and it resembles a stick figure you'd draw in third grade to fight space-travel beings, but it sounds Persian.

Thurlow works hard on his instruments and is patient. For example, it took him nine years to be able to coax the soul-lifting, multi-harmonic whirr from a hurdy gurdy-like machine. It's driven with a foot pedal connected by a bicycle chain to pulleys that turn rosined, leather-covered wheels.

Is he going after a certain sound when he builds his instruments? Searching for anything?

"I'm amusing myself is probably a better way to put it," he says. "Because if you're searching that suggests a destination." He laughs, "but you never get there. It's more like, 'what happens if you try this?'"

So he builds instruments "to be fun and intuitive" to play, that "rely less on specified skills and more on imagination and physical involvement." So anybody can play them. Hence, he says, "it puts the folk in folk music." He's right. It doesn't take much to make expressively sweet sounds.

If there's a single design philosophy it's probably this: It's about realizing—and drawing inspiration from—the idea that all music, through the centuries, was indigenous, fiercely regional, and defined by sounds and ideas that rose from immediate surroundings, by origin or ethnicity. Musical practices developed according to the means of making sounds that were available in whatever places folks lived, whatever country, or town, or tribe. There was never a line between performer and audience.

With that philosophy Thurlow started a collective called Anarchestra in which he's the only revolving "member," using the pseudonym Alex Ferris. Anarchestra is centered on Thurlow's instruments but when the collective does the rare appearance, like it has at various Tucson-area fringes fests, it's hierarchy-free — that is, no line between performer and audience.

"When I set up a show, everybody's allowed to play," he says.

Others outside local fringes are taking notice. One YouTube Anarchestra mini-doc, called Strange Musical Instruments Never Seen Before — Man Invents Hundreds of Them boasts three and a half million views. Fans from the world over track Thurlow in Tucson; he recently entertained visitors from Germany and Louisiana and a band from Australia keen to use his instruments on their next album. An out-soon Fede Alvarez movie, Don't Breathe, features Thurlow's work; soundtrack composer Roque Baños traveled to his compound and recorded a number of Thurlow's instruments.

Then there are his 25 instrumental albums available free on Anarchestra's Bandcamp page. Each is persuasive, fluttering between instrumental folk traditions and modern-day experimentations and orchestral beauty. There are meditations and sonic treatises on melancholy and joy, and hundreds subtle aural suggestions exist in corners of his tunes: imagine trance-like accompaniments to a Sufi dances; railroad cars rolling through desert flats; sultan processions in Ottoman Turkey; slow drunken boats to China; the drunk at the end of a smoky bar at last call.

For example, '04's aptly titled Bathtub Music is a drum-less dreamscape of ambient stringed things and plucks and odd, hypnotic time signatures. Last year's Solipse is, as he says, "the product of a year long meditation on dying" and its 13 songs demand attention while encouraging sadness. Tom Waits or Ólöf Arnalds would've killed for its tones and rhythms.

Thurlow plays all instruments on some; others feature collaborators, such as gifted Tucson musician Jorge Rico.

With his instruments and music he's created a kind of polyglot, and he agrees.

"Say a kid grows up in Cairo or Hong Kong, or some international place," Thurlow says. "And they grow up hearing all these different languages, and among themselves they'll speak in a language that goes in out of English and Arabic, this and that, with some French and Italian words thrown in, and something from the Sudan and so on. It's still a language, a form of communication. So bits of all these different things go into make up their total language. I would say what I do is sort of like that."

Back inside his dark house there's a library crammed with physics and feminist theory, philosophy and history, and a curious wall collection of hundreds of evenly shaped snapshots of those Thurlow has looked up to throughout the years—jazz greats, intellectuals, poets, scientists, authors. It's a kind of holy wall, a tool for his inspiration, a way to keep his heroes close. His living room doubles as recording studio and in it stands what looks like a replica of a dirty-gold rustbelt city refinery: dozens of Thurlow's handmade wind instruments of varying sizes, shaped from pipes, steel and copper, are arranged upright on a stand. He lifts a flute-like cylinder and blows a little melody.

Then he talks of his pop, a legally blind Wall Street Journal columnist who spoke many languages and was "a classical music snob." Thurlow credits his dad for his early musical knowledge and sonic curiosities, and by the age of five, he had Beethoven and Bach and Mozart sound-wired into his DNA.

He laughs, "My dad ran off with the babysitter ... " He pauses, adds, "then I realized how heroic my mother was."

Mom worked her way up from typist to curator of painting and sculpture at the Newark Museum.

Along with his brother Paul, Thurlow bored of playing rock music while cultivating obsessions with jazz and Ravi Shankar ("I saw him when I was 14 and it totally changed my life"). Then he played punk-rock free-jazz guitar for years in east-coast hand-to-mouth bands Demo-moe. (1980s) and Feral Logic ('90s). Name a trade, he's done it: fisherman, carpenter, welder, auto mechanic, mason, housepainter.

All experiences to inform his current creations, the genesis of which rose from the time he attempted to purchase a used bassoon while living in New York City.

"It was $1500," he exclaims. "I mean; I never even paid that much for a car!" So on New Year's Eve '00 he decided to build his own instruments, and began. He singles out instrument designer/musician Bart Hopkin, who authored Making Simple Instruments in the '90s, as another inspiration.

Thurlow split the east coast for Santa Fe, New Mexico, stayed several years before landing in Tucson around '08. (He lived in Tucson temporarily in the '90s, adored its "end-of-the-world" beauty.) He has been at The Vine ever since.

Since '00 he has designed and built a few hundred instruments. He won't sell them. "It's not about the money," he says. He's surviving on proceeds from Cape Cod land he inherited and sold. I ask what happens when that money runs out.

He exhales, laughs. "I keep hoping someone will come along and say 'I can really exploit this guy,' and make me some real money, and give me veto power over how embarrassing it is. I'm not greedy." After pausing, he adds, "In three or four years I'll be broke and homeless."

Go to anarchestra.bandcamp.com, and visit his website at anarchestra.wordpress.com.