From the idyllic shelter of Peck Canyon outside of Nogales, Edith Lowell reflects on what it's like to share her beloved ranch with violent drug-smugglers, illegal aliens and automatic-weapon-toting bandits.

Her opinion might surprise.

"We actually feel safe here at the house, I guess because anybody who is a bad egg has always gone on by, and we hope they keep doing it," she says. "But we know we have to keep our eyes open. We've been lucky. Poor Mr. Krentz wasn't so lucky."

For borderland residents living with the spillover from the Mexican drug wars, luck is a necessity, a commodity to be prized above all others, because it can spell the difference between a good day in paradise and a very bad one.

Rob Krentz was working on his ranch near Douglas in Cochise County on March 27 when he ran into the wrong person and was shot to death. The killer, his identity and motive unknown, is still at large.

Krentz lived in an area, the Chiricahua Corridor, that has been pounded by illegal aliens and drug-smugglers for years. The crossers are growing ever more aggressive, with break-ins, home invasions and late-night phone calls threatening retaliation against citizens fighting to shut down drug routes on their land. The federal government was ineffective, even condescending—until finally, shots were heard around the country.

Something eerily similar is happening in another part of Arizona's border, the place Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano says is "largely secure."

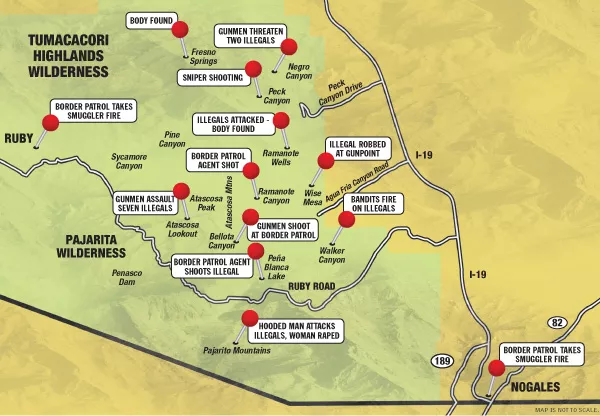

Call this increasingly dangerous smuggling route the Peck Canyon Corridor.

It begins west of Nogales, at border-crossing points stretching from the Pajarito Mountains and the Pajarita Wilderness all the way east to Cobre Ridge. It crosses Ruby Road and climbs into the Atascosa Mountains. From there, at more than 6,000 feet, the corridor follows the drainages down into Peck Canyon, which divides the Atascosas from the Tumacacori Mountains. Virtually all of this is Coronado National Forest land, where Americans go to hike, hunt and camp.

But for David and Edith Lowell, the land is home. Since 1975, they've lived on the Atascosa Ranch headquartered in Peck Canyon, 11 miles from the Mexican border.

"As far as I'm concerned, what Napolitano is saying is a flagrant lie," says David, 82, an explorer and geologist. "We have the misfortune of living on a very active smuggling route, and in the past year, we've had five shootings on my ranch, including a Border Patrolman. It annoys me the government can't stop these crimes from happening right under their nose. I'd say it's gotten significantly worse for us, rather than better."

Jason Kane, who lives on the edge of the forest four miles south of the Lowells, says the situation at his house, in Agua Fria Canyon, has calmed down since August. But from January through July this year, he heard gunfire coming from the national forest on a regular basis, some of which could've been hunters.

But on at least four occasions, Kane has heard what he's sure were gunfights involving one fully-automatic weapon firing, and another pumping back return fire. He has also seen ultra-light airplanes swooping over the mountains at night to drop drug loads, and he calls law enforcement often enough to keep the phone numbers of the Border Patrol and the Santa Cruz County Sheriff's Office affixed to the family refrigerator.

Like the Lowells, Kane says he feels generally safe right around his home—although his wife, Clair, does not—but the children aren't allowed to play in the yard unless one parent is watching. Kane added he felt compelled to speak up in spite of possible danger, because the public needs to know, and other Tucson media have shown no interest.

As for venturing beyond his property onto the national forest west and north of his home, Kane won't do it, and he advises hikers and hunters to stay away. "I grew up riding all over this country," says Kane. "I've gone back into places most people will never know about. But I'd never go there again by myself. Only with a group, and only if I was armed. That's flat-out. I mean, this craziness of the border being secure is a joke."

The Nogales International newspaper (which, like the Tucson Weekly, is owned by Wick Communications) has been ably chronicling the disturbing violence occurring in the Santa Cruz County backcountry, usually by assailants carrying automatic weapons and wearing black or camouflage. On June 18, the paper reported there had been more than 50 borderland robberies, assaults and shootings since April 10, 2008, including nearly a dozen people shot, with three killed.

But the number has risen since June. Including all of 2008 and going through mid-November of 2010, there have been almost 70 such episodes reported to the county, says Lt. Raoul Rodriguez, head of criminal investigations for the Santa Cruz County Sheriff's Office. "There are probably many more out there that go unreported," says Rodriguez.

It should be noted that while these incidents occur in the Santa Cruz boondocks, the settled areas of the county haven't experienced a major uptick in crime. In most categories, crime in the county between 2008 and 2009 either stayed the same or dropped, according to FBI statistics. A notable increase came in violent crimes, the number of episodes rising from 5 in 2008 to 18 in 2009.

The figure for 2010 is expected to be down, says Rodriguez—in spite of the Oct. 18 discovery of a body in a shallow grave on a ranch near Tubac. Javier Adan Mendez-Celaya, an illegal alien from Sonora, had been shot multiple times in what investigators believe is a drug murder. No arrests have been made.

In Nogales, itself, crime dropped in all but one major category in the same period. In addition to more than 60 of its own officers, Police Chief Jeff Kirkham says the city is home to 800 working federal agents, from the Drug Enforcement Administration, Border Patrol, Immigration and Customs Enforcement and other agencies. "We have more law enforcement per capita than anywhere in the state," says Kirkham. "For the average citizen, the average person visiting, Nogales is absolutely safer than Tucson."

But in the remote areas east and west of the city, the much-feared spillover from the Mexican drug wars is occurring. Most troubling is the willingness of gangs to use lethal force against lawmen. Since late 2009, there have been at least five episodes in which Border Patrol has taken fire, and the Nogales police have faced similar danger.

In early June, at Kino Springs east of the city, two off-duty policemen on horseback captured two drug loads in the same week, resulting in a threat against city police to "look the other way, or be targeted by snipers or by other means." As a result, Kirkham says his department is giving assault and ambush training to officers, and he has advised them to wear bulletproof vests if they ride horses at Kino Springs.

But the majority of the trouble is occurring west of the city along the Peck Canyon Corridor, which parallels Interstate 19 on the west, the same land Rep. Raúl Grijalva has proposed turning into a federal wilderness.

What's going on? Can the violence be stopped before we have another borderlands tragedy involving an American citizen or a lawman?

The episodes are clearly fallout from the relentless traffic in human beings and drugs across our border. But after that, answers are elusive, because no one has been arrested for any of these crimes. Sheriff's deputies, often called to the scene hours after the fact, find victims terrified and exhausted after running long distances over remote terrain to escape, and are frequently unable to say exactly where the crime occurred. And victims rarely provide good descriptions of assailants; the incidents often happen at night, and victims sometimes tell investigators they didn't look at the suspects for fear of being shot.

The witnesses could be lying, too. "Someone who is robbed is never going to admit they brought in drugs themselves," says Santa Cruz County Sheriff Tony Estrada.

Rodriguez describes these episodes as crimes of opportunity likely committed by competing drug cartels that find it easier to steal a load after it has been brought across the border, rather than bringing it across themselves. These bandits—known as bajadores—sometimes work so close to the border that they can "cross easily back into Mexico without having to worry about our response time," says Rodriguez, and they keep watch over smuggling routes. When a group of illegals or drug mules enters the country, they follow and set an ambush, stealing whatever valuables they can.

The assailants could also be from this country, gunmen from Tucson or Phoenix who work with the cartels, or independent thugs making money ripping off illegals and drug loads. Investigators can't rule anything out. "These individuals usually wear some type of bandana or ski mask and dark clothes," says Rodriguez. "There's nothing to help us identify them as either Americans or Mexican nationals."

Border Patrol spokesperson Colleen Agle says those who cross into that "very remote region become easy prey for somebody looking to exploit the situation." Estrada says smugglers use the forest west of Interstate 19 because they're trying to get around Border Patrol's checkpoint at kilometer 42. He adds his department has five deputies per shift to cover 1,200 square miles, and doesn't "have the luxury of patrolling the mountains and canyons."

"If we get calls from out there, we respond," says Estrada. "But patrolling that area is up to Border Patrol. Drugs and aliens crossing the border is their responsibility."

The borderlands north and west of Nogales have always been wild. During the Apache Wars, renegades used that country to raid the United States and escape untouched back to the Mexican Sierra Madre.

Peck Canyon gets its name from rancher Al Peck. His wife, daughter and a ranch hand were brutally murdered by Geronimo and his band when they stormed through the canyon on April 27, 1886, his last raid in Arizona before surrendering that September. David Lowell's grandfather sat on the coroner's jury for Geronimo's killings.

The area today is still extremely remote, largely unpopulated and federally managed. Countless smuggling trails cross the terrain, many leading into the mostly road-less Atascosas. Estrada says these mountains are so rough that on some occasions, his investigators, unable to reach areas by ATV or even horseback, have had to be dropped in by helicopter. The terrain puts law enforcement in a reactive mode.

"Once smugglers hit that country, you have no capability of knowing where they're going, and they have days to move a load through," says Keith Graves, who worked for 10 years as Nogales district ranger for the Coronado National Forest. He is now a liaison between the Forest Service and the Secure Border Initiative. "Even if they trip a sensor, there are only certain things Border Patrol can do. They usually have to wait until the smugglers come out."

Peck Canyon is a hot spot, because it offers an easy exit route from the Atascosas to Interstate 19, three miles east of the canyon entrance near Rio Rico.

Based on descriptions he has received and his own deduction, David Lowell believes the three sniper-style shootings that have occurred in Peck Canyon—on Nov. 21, 2009, and June 11 and July 2, 2010—have all been in a very narrow area about 3/4 of a mile long and less than a mile behind his house. "Shooting a high-powered rifle at a man in the open at less than 100 yards is a fish-in-a-barrel shot," says Lowell, adding that he believes it's no coincidence that most were shot in the arm or leg. "I think it's a message that 'this is our corridor,' belonging to ABC cartel or whatever, 'and go no further.'"

Edith says thieves have been robbing illegals crossing the mountains for some time. "But now we have bandits shooting at them, and that's something new," she says.

Jim Cuming, who lives near the Lowells, saw the result on Nov. 21, 2009, when David Luna Zapata, the victim of a sniper shooting, showed up at his driveway about 10 p.m. Responding to his barking dogs, Cuming went out and found Zapata bleeding profusely from bullet wounds in the thigh and ankle.

"I got him a chair and sat him down," says Cuming. "He was in obvious pain. The light was not bright, but I could see his pant leg was soaked in blood."

Before his family stopped ranching in 2000, Cuming, a landscaper, says it was rare to see even a footprint in those mountains. Today, he says the Peck Corridor is marked by 2-foot-wide trails.

"With the economy like it is, the majority coming now aren't looking for work," says Cuming. "I think they're part of the drug industry."

That trend is evident in other areas of Arizona's borderlands, where residents report seeing fewer workers and more drug activity. In the Chiricahua Corridor above Douglas, scene of the Krentz murder, drug-trafficking continues, says Don Kimble, who lives on the corridor's eastern border in the Peloncillo Mountains, a hot spot. "If I sit outside on still nights, I can hear mules talking at my well west of my house," says Kimble. "Drug-smuggling might've gone down a little since Rob's murder, but not much. When they need to send a load, it's going to go. They still cross at will."

Arrest numbers in Border Patrol's Tucson Sector indicate that crossings in general have dropped in the past few years. In fiscal year 2007, agents arrested 378,000 people in the sector. By 2009, the number had dropped to 241,000, and in 2010, the arrest number was 212,000. It sounds like good news, but caution is in order, says Brandon Judd, president of the local chapter of the National Border Patrol Council, the agents' union.

He says the Obama administration, desperate to pass comprehensive immigration reform, wants to convince the public that the border is secure, so they deliberately under-staff remote mountainous and desert areas to keep arrests down, allowing Napolitano and others to claim their security efforts are slashing crossings.

Judd says better enforcement has indeed made the border more secure in some areas—such as right behind the new fencing east and west of Nogales, where most of the new agents have been placed. But staffing hasn't been increased in remote regions, including the mountains west of Nogales. "The border in those areas is as wide open as it has ever been," says Judd.

Certainly, the woeful economy is another big factor in the drop in arrests. But bigger still, at least in some areas, is the spectacular drug violence in Mexico. As cartels fight each other to control land in northern Mexico, and very profitable routes on American soil, normal life, including migrant traffic, has changed dramatically.

In Sasabe, 45 miles south of Three Points, Alice Knagge says the gang that controls Sasabe, Sonora, right across the line, has frightened everyone so badly that everyday commerce has virtually stopped. "People don't come across to shop here anymore," Knagge says. "My business is down 40 percent in a year and a half." The crowds of illegals who once rushed across the surrounding Altar Valley—as many as 4,000 every 24 hours—have diminished as well, some diverted by fencing and additional agents in the Baboquivari Mountains.

Life has also changed to the east, at Jim Chilton's ranch outside Arivaca, the eastern border of which abuts the Peck Canyon Corridor. He has ended his "very friendly" practice of offering water to passing illegals. Now, with the gangster threat, if he sees a group coming over a hill, he quickly turns and rides away on his horse.

And he no longer carries a cell phone when he rides. Chilton says Border Patrol has warned him not to, saying he could be shot if traffickers see him on the phone. "We have a policy of not reporting to Border Patrol anything we see for fear of the cartels taking us out," Chilton says. "We have to ride our border fence three times a week, and we're highly concerned about running into a drug intrusion and being attacked.

"The fact is, every time I ride, I go out knowing I might be shot," Chilton continues. "But I have to decide if I'm a cowboy or a wimp. I live in this area. This is my home, and I am not running from it. I am prepared."

Chilton's neighbor, Tom Kay, says Border Patrol agents have warned him not to go to the southern part of his ranch bordering Mexico unless absolutely necessary. They say cartel scouts, who set up observation posts on hilltops to guide loads north, are now carrying rifles, as well as infrared binoculars and satellite radios.

"I have to go down there to work, or give up my ranch. I have no choice," says Kay, adding he's always armed and usually accompanied by a cowboy. He says illegal crossings of his land have plunged from as many as 1,500 a day four years ago to about 25 now. A big drop followed the July 1 gunfight between rival cartels at Tubutama, Mexico, leaving a reported 21 dead. The battle occurred 12 miles south of Kay's ranch.

"They're not coming our way, because they're afraid of being shot," says Kay. "Our ranch is almost normal in that respect, the best since we've been here. Border Patrol is much stronger than ever, going by our house both ways, all day. But it's also much more dangerous than ever. The Border Patrol, going to the southern part of my ranch, now carries rifles, too. They consider it extremely dangerous there, even for them."

While Napolitano boasts to the country that the border is "largely secure," some ground agents in her employ, and the residents they work hard to protect, describe something entirely different.

Does criminal activity inside the Peck Corridor make that land unsafe for recreation? Shane Lyman, acting district ranger in Nogales, referred the Weekly's questions to Heidi Schewel, spokeswoman for the Coronado National Forest. Schewel said she'd call back to talk about the safety of American public land but failed to do so.

But Keith Graves says he's worked the area, often alone, for 12 years with no problem, and that the Coronado has had no complaints from people who've been accosted. "As long as you're not stupid, it's safe to go in there," says Graves. "But take precautions. It's like camping out in Montana without managing for grizzly bears."

He says if you see backpacks or packages wrapped in burlap, leave them alone. If you see a group that doesn't fit the surroundings and doesn't look like a hiking club, go the other way.

Graves' biggest fear is vigilantes announcing they're going into an area to stop drug-smugglers, putting hunters in danger. "A bandit won't know if I'm a deer hunter or if I'm out to find him," says Graves.

Those who live inside or on the edge of the Peck Corridor are more wary. Nogales native Ramiro Molina, who has a home in Agua Fria Canyon, says he'd probably still hunt the Atascosa Mountains. "But I wouldn't feel comfortable camping there with my kids, that's for sure," says Molina. "I'd get in the car and go somewhere else."

A rancher at the southern end of the corridor, who asked for anonymity, says drug-smugglers try to move through quickly and stay away from campers. "But if you're in the wrong place, and suddenly they're there, it can be dangerous. The smugglers get braver and braver all the time. They've infiltrated this whole area and think they own it."

Rancher Dan Bell agrees that it's a crapshoot. "You never know what you might run across, and you don't know what those guys might think when they see you," he says. "Rob Krentz was out checking waters when he was killed. You just don't know anymore. If you're going to go, go in a group. Don't go alone."

David Lowell, who believes the shooters are coming from across the line, says, "My advice is to stay out until our government pulls itself together and does more to exclude these Mexican criminals." He and Edith used to go on a once-a-year family camping trip in Peck Canyon. But they've stopped, "feeling we might be robbed or assaulted with so many of these people crawling around in there. So we're no longer willing to camp on our own ranch."

As Edith says, "These shootings from ambush are very sobering. When I have a guest who wants to hike, I no longer tell them, 'Great, just walk out into Peck Canyon by yourself.'" But she says day-hikers or picnickers who go in groups, stay alert and don't confront people will likely have no problem.

It might be different, though, for hunters who camp in the mountains for days at a time. Edith says her dermatologist, who has hunted the area for years, stopped doing so after an encounter with drug mules escorted by men carrying rifles. The gunmen told the hunters they were working with Border Patrol. The hunters pretended to believe them, and the groups parted without incident. "That kind of thing doesn't happen all the time, and with luck, it won't happen at all," Edith says.

But the Lowells don't rely much on luck. They've installed even more security at their home, in the form of perimeter motion lights, some linked to sirens, and they're hyper-alert to the barking of their loyal springer spaniel, Ginger. They also regularly clear the thick brush at the end of their driveway, where four active drug trails converge.

The smugglers, oblivious to Janet Napolitano's "largely secure" border, use that brush to hide their drug loads until someone comes to haul them north.

VIOLENCE ON THE RISE

The following is a partial list of episodes that have occurred in the Peck Canyon Corridor in the past year. Except for two incidents involving the Border Patrol, all information comes from incident reports reviewed by the Tucson Weekly at the Santa Cruz County Sheriff's Office:

• Nov. 21, 2009. Men dressed in black fire at eight illegals in Peck Canyon with automatic weapons, wounding David Luna Zapata. He runs through the mountains for an hour before reaching Jim Cuming's house and calling for help.

• Nov. 27, 2009. A hunter in Fresno Canyon, two miles north of Peck Canyon, finds the body of a Hispanic male, shot to death. When Border Patrol backtracked, they spotted "four scouts in a cave and attempted to apprehend the subjects." The agents also "spotted three subjects walking on the same route with seven subjects approximately 10 minutes behind." The men are believed to be drug mules.

• Dec. 27, 2009. A sniper shoots a Border Patrol agent in the ankle in Ramanote Canyon, on the Lowells' ranch, about two miles southwest of their home. Two agents had entered the canyon after spotting a subject "possibly carrying a marijuana bundle."

• June 11, 2010. Two men wearing camouflage and masks fire on seven illegals near Ramanote Wells, on the Lowells' ranch. As the illegals flee, they meet two more masked men, who also fire "multiple rounds at them." Manuel Esquer Gomez, wounded in the arm, says that as he and the other illegals flee, they stumble across a decomposing body with the head and hands missing, "possibly due to animal activity." The body is 200 yards from the Lowells' home. Pima County's Medical Examiner tells the Weekly the dead man is too "heavily skeletonized" to determine a cause of death.

• July 2, 2010. Hilltop gunmen fire at 10 illegals, likely in Peck Canyon (based on descriptions). Two aliens say they couldn't see the assailants, but bullets hit the ground around them. One man, running "as fast as he could down the canyon," is hit in the back. The illegals admit entering the U.S. three days earlier to find work in Tucson.

• July 7, 2010. Based on a reliable intelligence source, Immigration and Customs Enforcement warns that a bounty has been placed on Nogales Border Patrol agents. The alert says 20 to 25 snipers, possibly from the Beltrán-Leyva Cartel, are headed to Nogales, Sonora, to shoot agents. The alert says snipers would be paid $5,000 for each person shot and cautions agents "to remain vigilant, maintain awareness of their surroundings, and utilize body armor and long arms as appropriate."

• Aug. 28, 2010. Two men in camouflage carrying handguns approach two Hispanic males between Peck Canyon and Negro Canyon. The gunmen ask "in Spanish for the marijuana." The men say they don't have marijuana and flee. The incident occurs a mile from the Lowells' home, on the north side of Peck Canyon.

• Sept. 5, 2010. Snipers fire multiple shots, probably with a high-caliber rifle, at Border Patrol agents in Bellota Canyon, north of Peña Blanca Lake. An agent returns fire; no one is hit. Border Patrol agents also took fire inside the Peck Corridor on Aug. 9, 2009, near the town of Ruby, and on June 21, 2010, west of DeConcini port of entry in Nogales.

• Sept. 12, 2010. Three men carrying rifles and wearing bandana masks fire at two illegals in the Walker Canyon area, northeast of Peña Blanca Lake. No one is hit. One of the illegals says the assailants were in a "very green" area and "suspects they were growing marijuana." The victims entered the U.S. west of the border wall and walked through a large hole in the barbed wire fence, "big enough where ATVs have been passing through." They'd followed the ATV tracks for an hour when attacked.

• Sept. 14, 2010. Seven illegals report being assaulted near Atascosa Lookout, six miles west of Agua Fria Canyon. Jesus Enrique Perez-Mercado says the gunmen stole $200 from him and assaulted him when he balked at giving up his rosary beads. Perez-Mercado says the gunmen spoke English to each other but Spanish to their victims.

• Oct. 21, 2010. A man in a hooded jacket and carrying a cuerno de chivo, slang for AK-47, attacks nine illegals—five men and four women—in the Pajarito Mountains south of Peña Blanca Lake. He robs them, kicking some of the men in the stomach. He tells the women to strip and penetrates them with his fingers. He separates out one woman and rapes her, never removing his hood or relinquishing his weapon.

• Nov. 11, 2010. Three men wearing masks rob an illegal at gunpoint on Wise Mesa, in the national forest between Peck Canyon and Agua Fria Canyon. The assailants tell the man to leave the area and not return.

• Nov. 16, 2010. Border Patrolmen on horseback encounter 12 illegals two miles northwest of Peña Blanca Lake. An agent shoots one of the illegals in the stomach after the illegal reportedly threatens him with a rock.