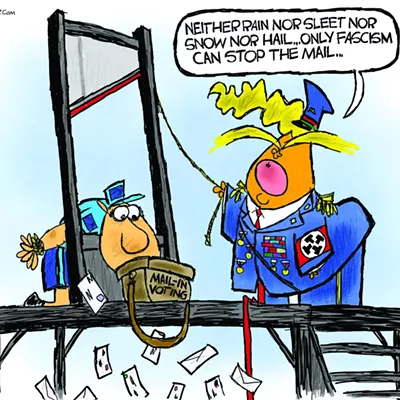

Desperate enough to assemble a slick multi-million-dollar campaign that dissembles at virtually every opportunity. The opponents of Prop 202 are spewing propaganda that's about as reliable as the average edition of the supermarket tabloid Weekly World News. By the end of October, don't be surprised to hear that the initiative is part of a secret alien plot to impregnate our women, mutilate our cattle and abduct our precious property rights.

It's no surprise that the Growth Lobby is terrified that voters might approve Prop 202, because it would dramatically alter the underlying dynamics that have been in place for most of the state's modern history. If it passes, voters would decide where future development occurs, while homebuilders will get dinged by steep impact fees.

Developers have long been accustomed to calling the shots in Arizona. They acquire land, rezone it, throw up houses, and leave the rest of us on the hook when it comes to building and staffing schools, extending roads and pipelines, and providing other public facilities like parks and libraries.

That freewheeling approach has helped make Arizona one of the fastest-growing states in the union in the last decade, with 1.15 million new residents since 1990. In Pima County, the population has jumped from 666,880 in 1990 to more than 842,000 today. Each year, homebuilders break the record for new home permits in Pima County. In 1996, 5,219 permits were issued; in 1997, 5,361; 1998, 6,547; 1999, 7,421. Through August of this year, 4,825 permits were issued, a slight slowdown from last year's pace.

While there isn't any shortage of claims by both sides, there's no definitive report on whether growth pays for itself. There are simply too many variables in communities across the state, not to mention different perspectives on the value of clean air, unspoiled views and abundant wildlife. Growth boosters point to the state's hot economy as evidence that development is fueling a boom. Critics point to the downside of growth: rising local taxes, more crime, lousy schools, brown skies and crummy jobs.

While growth has been generally good for state government, local jurisdictions have picked up the tab. Pima County's budget was $594 million in 1990; this year, the Board of Supervisors passed a record $840 million budget. And the climb in expenses isn't limited to the area of transportation and other infrastructure. Between 1989 and 1999, the county's budget for criminal justice climbed 71 percent, from roughly $75.5 million to more than $129 million. It's a simple equation: more people, more crime.

Up north, Maricopa County was the fastest-growing county in the United States between 1990 and 1997. But that growth has been accompanied by an interesting churn factor: for every three people who move to Arizona, two move away, meaning that many of the people who come here for a new life leave to find a better one elsewhere. And even among those who stay, there's a longing for escape. A recent Morrison Institute poll showed that 45 percent of Maricopa County residents would move tomorrow if they could, saying Phoenix has too many people, too much crime and too much traffic; besides all that, it's too damn hot.

Judging from the polls, the residents of Pima and Maricopa counties have certainly come to their own conclusions about growth: It's happening too fast and ruining the quality of life.

Given that prevailing attitude, it's not surprising to hear nearly every candidate for public office proclaiming that growth must be better managed. But whether that translates into meaningful public policy is another question. Gov. Jane Dee Hull's growth-management program, Growing Smarter, has been crafted by Growth Lobby attorneys and weakened further in the legislative process. (For details, see "Trick Or Treat," page 19.) But the underlying flaw is that planning remains a voluntary process for communities. There's no rush to use what few tools have been made available by Growing Smarter. Critics say the package is so tilted toward property rights that it makes planning for growth more difficult.

"If people are happy with the status quo, they'll just love these bills because they're not going to change the way we plan and manage growth in Arizona," said Sierra Club lobbyist Sandy Bahr last winter, as the Growing Smarter legislation was racing through a greased special session. "We think the main bill has provisions in it that could actually hinder efforts to manage growth better."

BAHR, OF COURSE, has a bias. She's been working to pass the Citizens Growth Management Initiative on the November 7 ballot.

If approved by voters, the CGMI would "force communities to go through the process of planning," says Joy Herr-Cardillo, a staff attorney with the Center for Law in the Public Interest, another organization that spearheaded much of the campaign. "It gives them tools to deal with the issue of growth, but it also provides a framework of things they have to address."

Counties, cities and towns with more than 2,500 people would have until the end of 2002 to draft growth-management plans. The plans would be shaped through public meetings and approved by a public vote. They would include urban growth boundaries, beyond which government would be restricted from extending public services like roads and sewers. (Hence the recent anti-202 TV spot featuring a family stuck using a porta-potty on the site of their dream house in the middle of the desert; the young son in the advertisement whines, "It's not fair!" as he's forced to use the portable latrine. The commercial sidesteps the question of why it's fair to expect taxpayers to pick up the tab of extending sewer lines to the family's isolated home.)

The initiative's backers deliberately left the shaping of each plan in the hands of individual jurisdictions, each of which would be responsible for developing the public planning process.

"The Sierra Club is not going to plan your city," says Herr-Cardillo. "There will no doubt be Arizonans who are members of the Sierra Club at the planning table, but developers are going to be there, businesspeople are going to be there, citizens are going to be there and educators are going to be there."

While local jurisdictions would control the process, there is a framework for the growth-management plans. When drawing the growth boundaries, each community would have to use Department of Economic Security projections to predict population levels in the next decade.

Critics complain that DES statistics often underestimate population growth, so using them as a baseline will mean no more building permits will be issued once that number is reached. "Absolute hogwash," says Herr-Cardillo. "There's nothing in this thing that limits the number of permits." She argues that the DES numbers provide a guideline to estimate how much land will need to be developed in a 10-year period. If the population grows at a faster rate, voters have the option of expanding the growth boundaries once a year through a public vote.

"If you're going to draw a boundary so far it's meaningless, there's no use in a boundary," says Herr-Cardillo. "The idea was we want to have boundaries that encourage more compact development."

Other incentives for compact development--which Herr-Cardillo defines as development that occurs near existing infrastructure--include the impact fees built into the CGMI. It requires developers to pick up the "full cost of additional public facility needs"--which translates into steep impact fees for roads, sewers and even schools. That would be a dramatic change in southern Arizona, where Pima County and Oro Valley (the only jurisdictions to enact impact fees) collect roughly $1,500 per new home. (Impact fees are often higher in Maricopa County, topping $10,000 in some communities.)

Impact fees could be reduced in "infill incentive areas," which are defined as vacant lots or vacant or deteriorating structures near existing infrastructure. The provision is designed to encourage revitalization of the inner city rather than continuing the trend of developing on the community's fringe.

The CGMI would also restrict the subdivision of agricultural and ranching properties, preventing them from becoming the next playground for developers.

Taking the planning process from elected officials and putting it in the hands of the public means that "the voters will have power and control in our communities," says Herr-Cadillo, "and that's what the development community finds so scary."

THERE'S NO DENYING that there's a current of fear running through the development community. Scottsdale developer and economic forecaster Elliott Pollack, who co-authored a report forecasting dire economic times should the initiative pass, likens it to the iceberg that doomed the Titanic.

Pollack delivers an entertaining PowerPoint presentation, but his song and dance is predicated on the notion that passing the initiative would cause an immediate two-year moratorium on development. The initiative itself calls for no such moratorium--in fact, it allows rezonings to occur during the two-year planning process with a supermajority vote--but Pollack has concluded that local governments may decide to stop issuing building permits to prevent potential liability.

Herr-Cardillo says it's more likely "you'll seek a rash of building in those two years" as developers scramble to get their projects underway before restrictions kick into place. "If the initiative passes, it won't affect any rezoning currently in place," she says. "Anything currently zoned or permitted can be built out in that interim. My understanding is that developers are going for rezonings right and left."

She's right about that: In neighboring Pinal County, for example, developers are racing to get approval of rezonings that would allow for 60,000 new homes, including a 34,000-home development near the small town of Oracle.

A second study, which cost the Arizona Chamber of Commerce, Bank One, Bank of America and the Arizona AFL-CIO $50,000, also predicted economic catastrophe should the initiative pass. A chamber press release predicted that more than 1.2 million jobs would be lost in the next 12 years if the initiative should pass.

Frightening numbers--and absurdly exaggerated. Within a week, the chamber was backing off the figures, blaming the media for misrepresenting them. A closer read of the report showed that it actually didn't predict lost jobs at all. Rather, it forecast that a potential 210,000 to 235,000 new jobs might not materialize.

The study was co-authored by USC professor Peter Gordon, whose pro-sprawl advocacy has made him a darling of developers across the U.S. Gordon concluded that "the CGMI will impose high economic and social costs while offering few benefits."

Both the Pollack and Gordon studies came under fire from Northern Arizona University economics professor William Hildred, who characterized Gordon's study as "bizarre."

"Citizens who are concerned about the initiative's impacts on production and employment are ill served by Gordon's and Pollack's analyses," Hildred says. "Arbitrary premises intended to demonstrate a single outcome do not produce results that increase understanding; their results obscure issues and mislead the public."

BUT THE QUESTIONABLE studies are just the start of the deceptive practices of the opposition. There are the sleazy tactics--like purchasing the URL www.yeson202.com to post their anti-202 propaganda--and then there are the Big Lies.

Take, for example, the frequently repeated suggestion that the initiative was written in secret by "San Francisco lawyers," as real estate heavyweight Bill Arnold recently declared during a radio interview. (Arnold has formed his own political committee, Citizens aGainst Mass Infill--CGMI, get it?--to campaign against the initiative.)

David Baron, the former director of the Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest who played a key role in drafting the initiative, says the claim is "a bunch of nonsense."

"Where did they get that?" asks Baron, who took a job last year with EarthJustice Legal Defense, a branch of the Sierra Club in Washington, D.C. (To defuse critics who might complain that he's an out-of-state attorney, Baron points out that he wasn't involved in the initiative effort after he left Arizona.) "It's just a complete falsehood. Utter fiction. We had dozens of meetings to discuss this and there were a lot of people involved in drafting it and I can't think of a single lawyer from San Francisco who was involved. It's just ludicrous for these people to be suggesting this was written by out-of-state people. It's especially galling when you think about the fact that a number of these large development companies are owned by out-of-state interests and are themselves represented by out-of-state attorneys."

While the Sierra Club has played a key role in the campaign, contributing at least $105,000, it's not the only group involved. More than 25 other environmental, business and labor organizations, including the Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest, the League of Women Voters, Arizona Common Cause, the Arizona League of Conservation Voters and the United Food and Local 99 of the Commercial Workers' Union, are backing the effort.

The political committee backing the initiative, Citizens for Growth Management, had raised $331,742 as of August 23. Much of the war chest had been spent gathering signatures; at the end of the last reporting period, Citizens for Growth Management had only $116,752 left in the bank.

Almost $19,000 had come in contributions of $25 or less. Those small contributions had made up about 67 percent of the individual contributions to the campaign.

Compare that to the more than $2.65 million raised by Arizonans for Responsible Planning, one of the political committees opposing Prop 202. The contributions to that campaign have come in big checks from developers, construction companies and other growth-related corporations.

The largest contributor to that effort has been the Arizona Rock Products Association, a group of companies that deal in concrete, gravel and rocks, which has contributed at least $404,000 to the campaign. Last month, the Arizona Rock Products Association created a separate political committee to campaign against Prop 201. In four weeks, that group has already raised $135,000.

The biggest complaint raised by opponents of Prop 202 is the provision that allows for citizen suits to enforce the measure. In TV ads and direct mail pieces, the developers' campaign says passage of the initiative will result in an unending stream of out-of-control litigation that will prevent you from even building a guest house.

"We have statutes in Arizona now that allow citizens to sue that enjoin violations of various laws and the fact of the matter is, they are rarely used," Baron says. "They are used in egregious situations. The reality is, the ordinary citizen who has a concern isn't going to take it to court unless it's a real and substantial one because of the cost. The people who are complaining about this are the people who have the resources to go to court whenever they want to."

Herr-Cardillo points out that state officials have a history of failing to follow laws such as the federal Clean Air Act. The Center for Law in the Public Interest has had to sue to make the EPA enforce the law.

"We ought to be able to require our public officials to follow the law, and that's all that does," Herr-Cardillo says. "It authorizes someone to bring an action in the face of a violation of this act. It doesn't give rise to money damages, so there's no monetary incentive to bring an action. It simply allows for injunctive relief. So they're suggesting there's this cottage industry of lawyers will spring up. I was in private practice for 15 years and I'll tell you that if there's not a monetary incentive, we don't bring a lawsuit."

Debunking every misrepresentation from the Growth Lobby is not unlike battling the mythological hydra: For every lie that's exposed, two more spring up to take its place. A recent enormous mailing reprinting the text of the CGMI in small print, accompanied by exaggerated annotations, drew a lengthy seven-point response from Citizens for Growth Management.

"This isn't no-growth," insists Herr-Cardillo. "It's about planning growth. We know growth is going to occur. I came here in '79 and probably would have been happy to close the door behind me. But the reality is my parents have come out, people are coming here. And if we don't plan for it, we're just going to continue to sprawl and continue to destroy what's really attracting all of us to Arizona."

Still, the big lies are having an impact. Early polls showed the initiative had the support of roughly 70 percent of voters. The slick campaign appears to be eating away at that support; a recent Arizona Republic poll showed support had dropped to 62 percent.

"We know that all of their money and advertising and misinformation will have an impact when people go to the polls," says Bahr. "We still feel good about the campaign and think the voters will see through a lot of this stuff."