In many ways, they are typical teenage girls, exhibiting teen angst and awkward wonder mixed with indifference. Then one girl reminds everyone else why they are all there, dressed alike in green pants, khaki shirts and rubber slip-on shoes. She says her name as tears well up in her eyes. She looks to the side to avoid everyone's stares.

"I really want to go home," she says.

The rest of the girls, sitting on tan-colored, molded-plastic chairs in a semi-circle, look at her and nod. No hugs are offered as the girl wipes the tears from her eyes. There are rules here: No physical contact is allowed, including hugs of comfort.

This is the Pima County Juvenile Detention Center, located off Ajo Way. Before the Tucson Weekly is allowed to come in, other rules are established. Do not identify the girls. No names. No faces or identifying marks, such as tattoos, in photographs.

Each Friday, these classes are held under the guidance of Madeline Kiser, a local poet and teacher who helped create Poetry Inside/Out, a program that combines experiences and poems written by teenagers on the inside--juvenile detention--with the experiences and poems of teenagers on the outside--students who attend Pima Vocational High School, an alternative school for kids who no longer fit in traditional schools for a variety of reasons, like behavior issues, pregnancies or a past that may include serving time in juvenile detention.

Kiser has been coming to Juvenile Detention since 2004 for Poetry Inside/Out, funded by the Friends of the Pima County Public Library, Tucson Parks and Recreation and Pima Vocational High School, among other organizations.

Kiser decided to create a theme for the program focusing on sustainability and community. In 2006, the theme was catalyzed by looking at water and stewardship. Kids from the Pima Vocational High School group traveled to arroyos and rivers, and visited bureaucrats in charge of water policy and planning. The kids would write poems about what they heard or saw, and those poems would then go to the girls in Juvenile Detention, along with a special guest who would talk about the topic to both groups of students.

The girls in detention then wrote poems in response, and those words traveled outside to the Pima Vocational students. The cycle repeated itself again and again.

That year, one of the guests was UA Professor Guy McPherson, an environmental-sciences teacher known for his writings on peak oil and his predictions that we may soon be living in a modern stone age.

McPherson says that after his first experience with Kiser and Inside/Out, he was hooked. He continued to join Kiser in the Detention Center classes for the rest of the year.

McPherson admits the pairing is unusual. After all, he has no children. He's an atheist. And, yes, he's certain oil is quickly running out and that our society will soon be collapsing as a result. But in the class, he found something he says he wasn't getting enough of in traditional academia--a much-needed dose of humanity.

Last year, McPherson decided to develop a new honors class that would look at the same issues that the Inside/Out program was examining: matters of sustainability and how humanity is dealing with global warming, transportation and McPherson's favorite topic, peak oil.

He required his students to join him and Kiser in Juvenile Detention each Friday, four at a time, and to write poetry that went to the students both inside and out.

McPherson looked at the opportunity as a way to bridge the sciences with humanities--but he also wanted to share the Poetry Inside/Out experience with his UA students.

"The first class I got to was at Pima Vocational High School. So, I'm looking out in the room. Some (students) are pregnant or have children, and they are talking about things like physical and sexual abuse, and I'm thinking to myself, 'I guess I'm not in Kansas anymore. This is not my kind of life. I've never experienced anything like this.' Then we go into detention three days later, and it was again a different world. ... All of them have had some experience with abuse, sexual abuse, drugs, rehabilitation--these are the girls in society who everyone thinks are bad," McPherson says.

"It was incredibly illuminating. I cried that Friday, and every Friday after for many, many weeks."

During his first semester of involvement, McPherson says, he was amazed by the program Kiser had put together, bringing in outside speakers ranging from Humane Society officials to the director of the Urban League to Holocaust survivors.

Last year, the first year McPherson's honor students were involved, the theme was transportation and sustainability. Kiser's co-teacher, Mary Goethals, got speakers from the city's Transportation Department and programs like BICAS, the bicycle cooperative, as well as Buddhist nuns who talked about spiritual transportation. It proved to be an especially big test for McPherson's students, who signed on not knowing that poetry and Juvenile Detention visits would be part of the class' requirements--because it was inadvertently left off the class description.

McPherson says one student, an engineering major, was irritated and called him to complain. But she stuck it out.

"I'll never forget her going with us and the Pima Vocational High students to (border artist) Valerie James' gallery in Amado and afterward breaking down, crying and hugging another co-teacher. That student is back in the class this semester," he says.

This semester, McPherson's students have continued to look at issues of sustainability, reading Derrick Jensen's controversial 900-page, two-volume tome, Endgame, about how Western civilization created the global environmental mess, and how civilization may need to be disassembled in order for the world to survive. Poetry and visits to Juvenile Detention remain part of the class.

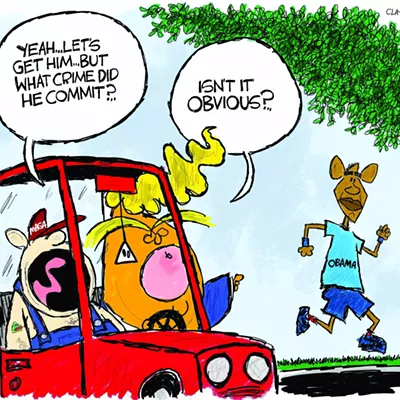

Goethals decided to examine politics since it's an election year. Guests have included a Barack Obama campaign organizer, a representative from the Republican Party, journalists, local politicians and even nuns from the Benedictine Sisters of Perpetual Adoration.

While building this bridge between science and the humanities, McPherson says he's gained a greater understanding of the similarities of human experience.

"The issues that make life challenging are what we end up discussing in each class, and the similarities between each group (of students) are often striking," he says.

While McPherson credits Kiser for the class' successes, Kiser says she'd be lost without her fellow teachers. In particular, Kiser points out Goethals, a retired English teacher who joins Kiser in each class.

Together, the two women almost work as a tag-team. Kiser asks the girls to think about the day's theme and how it relates to their lives, and Goethals works with them to put their thoughts down on paper.

Kiser smiles wide while coaxing out stories that most typical teenagers wouldn't share. On this day, the theme is forgiveness, as the Juvenile Detention students examine a post-election country in which everyone has to get along. Like every Friday, Kiser and Goethals have brought a special guest.

This week, it's Benedictine Sister Patricia Vereb. The week before, students from Pima Vocational High School visited Sister Patricia and her fellow nuns at their convent at the Benedictine Monastery, off Country Club Road.

Sister Patricia brings the monastery to Juvenile Detention by pulling out a screen, a laptop computer and a projector. She gives the girls a tour of her convent, the monastery and church where she lives and worships.

Who knew convents had gone high-tech?

She talks to the girls about forgiveness through her eyes--those of a Catholic nun. Kiser asks Sister Patricia how she thinks candidates like Barack Obama and John McCain, after tossing negative campaign jabs, forgive each other, and how people who didn't support Obama move on.

"It won't do any good to hold on to that," Sister Patricia says to the girls.

She shares her own struggles with forgiveness, and then suggests that the girls make what she calls a SFGTD (Something For God To Do) box to store notes to God about their worries.

"Once the matter is placed into the box, do not hold on to it by worrying about it. Instead, focus on all the wonderful things that are present in your life now," Sister Patricia reads. "What do you think of that idea?"

Some of the girls nod in agreement.

When Sister Patricia is done, Kiser leans in and asks what forgiveness means to each of the girls. They are reminded that forgiveness doesn't have to be about another person; forgiveness can be something they need to offer themselves.

The girls think for a moment. One says she regrets the day she sent a text message to her mother saying she wished her mother were dead. Another girl says she needs to forgive herself for all the drugs she's taken and the way she treated her mom.

"I need to forgive my mother for never being there when I needed her," another girl says.

Another adds that she needs to forgive her father for never being around, because he was always in and out of prison.

Once everyone is done sharing, Kiser announces it's time to write. McPherson goes to the security desk and gets numbered pencils to hand out. (At the end of the class, each pencil needs to be returned; the girls are not allowed to keep them.) From a plastic tub, Kiser pulls out a treat: Cheetos.

The girls smile wide when offered handfuls of the snack, reminding everyone in the room that although these girls can be tough, they are still teenage girls. They grab a pencil and paper, and sit on the floor, using the plastic chairs as desks. Goethals goes into action, going from girl to girl and asking them what they are thinking, meanwhile looking at what they've started to write.

There are no hugs to offer, but there is still an intimacy in the room as Goethals leans in to hear their whispers, and at times sits with them, shoulder to shoulder, as they talk about their words.

Then it's time for the whispers and the writing to end, and to read the words out loud.

"The bravest thing to do is read it yourself," Goethals announces, as the girls sit on their chairs, put the Cheetos on their laps and look down at their writings. Some girls pass their work to someone else to read, like McPherson or a UA student; others take Goethals up on her challenge.

"I'll read," one girl says.

"Mom, you are my queen," she begins. "I've seen you get hurt by all of this."

The girl continues reading the poem that honors her mother, laying out a story of a girl involved with gangs and drugs--who remains in desperate need of her mother's love, especially when she gets out.

While she reads, the girl's fellow inmates sit quietly. Some visitors--including Kiser--work to remain motionless while tears well up.

At the end of the class, the girls line up; the pencils are counted; the Cheetos are packed away. Goethals puts her hand on her chin in thought as she collects the poems and watches the girls walk away.

"I think they have open hearts despite what they've been through and what they're experiencing being here," Goethals says.

Kiser describes the class--moving from detention, to the UA and to Pima Vocational High--as one continuous poem.

"It's a serendipitous relationship and experience, with the different speakers and the different kids. ... There's also a level of intimacy involved that exists in poetry. Each week, we have this exchange of hand-written poems and communication," Kiser says.

"The poems are the eyes and the ears for the girls who can't travel. They see the handwritten words, the crossed-out words, and the kids become curious about each other. And eventually, there is recognition that 'I'm not the only one thinking of what life is going to be like in 20 years.'"

Kiser thinks Poetry Inside/Out is also touching a nerve with all of the involved students, kids who have been through a lot.

"These kids are begging to be involved, to be called to a higher purpose," she says.

But Kiser also sees another side to this poem: the contributions of the various guests, like McPherson, who have found themselves in a detention center for the very first time, talking to children who have felt the world on their shoulders at too young of an age.

One semester, Kiser says, a border activist came to the class. As she talked about her work, she began to cry and explain how much harder her work was becoming.

All of a sudden, the students were advising and comforting the guest.

"There was awareness that, 'Even with my own brokenness and the fact that I'm in here, I can still comfort somebody.' That meant a lot to those girls that day. The speakers open up to them. I think, for some, especially those who are policymakers, they get to meet a group that is often missing from the table, and hear what they are thinking," she says.

In that regard, Kiser says, she sometimes sees Inside/Out as being like performance art, meant to help the city understand another perspective, and to understand that these kids matter.

"I have felt enormously lucky. This is an example of doing what writing is supposed to do: You need to speak out, no matter what that brings," Kiser says.

"It's also about our future: How can we prepare a new generation to address this crisis? In college and other schools, education centers mainly on individual success and test-taking. That doesn't provide young people with the skills needed to address a world in flux. In this setting, we teach flexibility. It's what this world is going to require in the future."

When it comes to flexibility and looking at the world from a different perspective, Nick Jones gets it. This is the second time the UA student has signed up for McPherson's honors class. And like his professor, Jones is hooked.

"Last year, all I knew was I was taking a course on sustainability and the human experience. ... I like science, and I'm pro-environment. Then a week before, we all got this e-mail from Guy that we'd be going to a detention facility. I was thinking, 'This wasn't what I was signed up for.' I was freaking out. I didn't want to be with criminals," he says.

Jones says that as he watched Kiser and Goethals work, he discovered something he never expected: He connected with the students in Juvenile Detention.

When the first class ended last fall, Jones contacted Kiser and asked if he could continue to come to detention. And after the class ends this semester, Jones will work with McPherson to do an internship with Kiser for independent-study credit.

"At times, it is sad. There are a lot of repeats, kids who come back. And many of them say, 'I'm going to change my life this time,' but we see them back, sometimes only three or four days after they left," Jones says.

"I never used to open up about any of the problems I was having, then I see these girls so willing to open up to you--it's therapeutic for them. At first, I never related it back to myself. Then I realized I should try this. I needed to open up in my own life."

His work with Poetry Inside/Out made Jones look at his future differently, too. Jones, 20, has settled on history and anthropology as majors, and decided he wants to go into the Peace Corps after graduating, working in Kenya or South Africa. Then he's off to law school and work as an attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union, he says.

"This class kind of drives it home. I had a really blessed life. I'm not religious, but I recognize I've had a supportive family, and I've always had enough money. I believe you try

to leave the world a better place than you received it.

"I also used to be a very science-oriented person. I used to think that the (environmental) problems we might have will be fixed by science. I still hope for that, but I know now we can't get out of this self-destructive mindset without community. You need to stick out your neck for people, and hope they are going to stick out their neck for you someday," Jones says.

Kiser agrees with Jones regarding the importance of community--and she thinks poetry can help build that community.

Thirteen years ago, Kiser was living in Oakland, Calif., with her husband and children. Her husband, a native of Costa Rica, wanted to go home, and Kiser found herself with two young children in the big city of San José, not knowing a soul.

"Neighborhoods rich and poor had armed guards, and many neighborhoods were poor. The city was filled with smog and contaminated. I began to think I'd not have grandchildren," she shares, her eyes tearing up.

"I began to write poetry."

What followed was a recognition that poetry can offer a way to look at wider issues. When Kiser and her family moved to Tucson, Kiser began working with local teen-art program Art in Reality, and then became a writer in residence with the federal prison system before creating Inside/Out.

Cameron Conaway, a UA poetry grad student and the UA Poetry Center's high school poet in residence, has joined Kiser and Goethals in the classroom. He's using his experience with Inside/Out for his master's thesis, specifically looking at the importance of allowing oneself to be vulnerable and using poetry to find one's voice.

One week, Conaway talked to the group about vulnerability, and even used his own experiences as a cage fighter in a discussion on physical vulnerability. He talked to them about being more open--and asked them what could happen as a result.

Kiser says the reaction was interesting and eye-opening. The bottom line is that in most of these girls' lives, there is no room for vulnerability or opening up. Doing so could be a matter of life and death, like getting hurt on the streets.

But surrounded by the white walls of the meeting space in Juvenile Detention, the girls can and do open up. In the hour and a half they are given with Kiser and Goethals each Friday, poetry finds a place in their hearts.

"It's bringing joy to a fractured world through the power of the human voice. There's a joy in hearing another person's voice tell their story. Hopefully, it also means we learn how to tell a different story, the kind of story that changes the world," Kiser says.