The trial in Tucson City Court of one of their own on an assault charge had dragged on in a utilitarian room for 2 1/2 hours. The hard wooden benches, upon which witnesses and spectators sat, had become a pain in the ass.

Applause, sweet applause erupted after the folksy Judge David Dingledine declared Robert Swango, 59, innocent. He then threw off his black robe and rushed out the door to a courthouse in Marana, where he was due, unrealistically, in about 15 minutes.

There had been a few touch-and-go moments for the atheists: Swango, a stroke victim with aphasia, had struggled to articulate why he felt threatened when a young man started pestering him about the red-lettered "God is Fake" sign he was displaying on the southeast corner of Grant Road and Campbell Avenue. Swango's supporters had murmured in disapproval when they perceived things weren't going their way, once drawing a rebuke from Dingledine after city prosecutor Mike Spriestersbach (whose last name contains the word "priest," one atheist noted) complained.

Naturally, the two sides in the case--with the defendant representing himself--painted different pictures of the events leading to the assault charge: the prosecution of a provocateur itching for someone to take offense so he could inflict pain; the defense of a mild-mannered gentleman exercising his not-so-God-given rights.

What both sides could agree on was that Olaf Ison, 22, had seen Swango standing on the corner, had approached him and, at the very least, had been persistent in attempting to see the sign the organizer for Tucson Atheists was holding. Swango claimed Ison had tried to snatch the sign away from him, but none of the witnesses who took the stand corroborated his story.

In the end, Swango said he felt threatened by Ison. A few weeks before the two men would meet, his sign had provoked a violent reaction in another man, who reportedly "beat the shit" out of him. After that, he held the pepper spray in his hand whenever he took to the street with his sign.

Swango sprayed Ison twice--the second time when Ison walked back for some more after heading into Walgreens to get something to wash out his stinging eyes. The encore spraying prompted Ison to throw a 2-liter bottle of Coke at the atheist.

When asked why he puts himself in these potentially dangerous situations, Swango said it was for the good of the young.

"It's for the kids, the children--they're not coming after me," he told the Weekly. "And the adults, they just don't know any better. And, besides, good Christians, they just give me the thumbs down or just stop and try to witness to me. I understand the good Christians, because I used to be one."

The court case was a small victory for atheists in a much larger war, as groups of like-minded freethinkers struggle to find footing in a country where religion is "in." It's difficult to ascertain the number of atheists in the United States with any certainty, but cited figures ranging from 3 million to as many as 15 million may be low. Regardless, atheists have a steep hill to climb in terms of gaining wider acceptance.

Professors Penny Edgell, Joseph Gerteis and Douglas Hartmann at the University of Minnesota released a study in the April 2006 issue of the American Sociological Review that found atheists have the honor of being the least-trusted minority in America.

University researchers surveyed more than 2,000 households by telephone and found that 39.6 percent of people selected atheists from a list when prompted to say which group doesn't share their vision of American society. That beat out Muslims (26.3 percent) and homosexuals (22.6 percent), two other minorities reviled by segments of the population.

Similarly, the survey found 47.6 percent of respondents would disapprove of their child marrying an atheist, ahead of Muslims (33.5 percent), African Americans (27.2 percent), Asian Americans and Hispanics (both 18.5 percent), Jews (11.8 percent), conservative Christians (6.9 percent) and white people (2.3 percent).

Edgell theorized in a press-release that their "findings seem to rest on a view of atheists as self-interested individuals who are not concerned with the common good."

So-called "New Atheists" have been stirring up trouble, too. In the November edition of Wired, prominent freethinkers Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris discussed their recently released books, The God Delusion and Letter to a Christian Nation, respectively. In his Wired interview, Dawkins advocated for less tolerance of religious myths, which he believes are disempowering the human race.

Let's not forget the seemingly endless battle over teaching intelligent design--aka creationism--in public school science classes, which many atheists are naturally opposed to. And the fight rages on over the words "under God" in the Pledge of Allegiance, inserted more than a half century ago to highlight the difference between righteous Americans and amoral Soviet pinkos. (Oddly enough, the original pledge was written by a socialist Baptist named Francis Bellamy in 1892.)

Then there's our president, who wraps his faith around himself like a mink stole. A Nov. 19 Associated Press story quoted George W. Bush as saying he had taken "a moment to converse with God" after he emerged from a Vietnamese Catholic basilica during a visit to Hanoi.

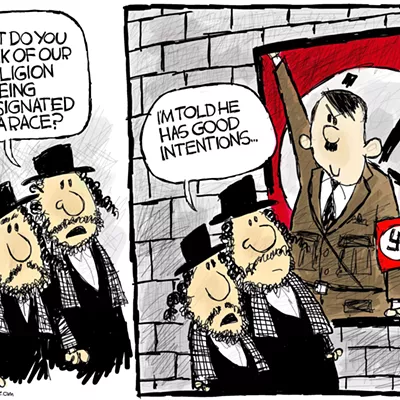

But it was his father who is believed to have uttered one of the most famous quotes about atheists in American society, while campaigning for the presidency in 1987. Atheistic journalist and activist Robert Sherman attributed the statement to him after he asked Bush whether he recognized "the equal citizenship and patriotism of Americans who are atheists."

"No, I don't know that atheists should be considered as citizens, nor should they be considered patriots. This is one nation under God," Sherman quoted Bush as saying.

Current press notwithstanding, it seems like atheists are often the ones being talked about, not doing the talking--particularly in politics and public-sphere discussions. So the Weekly asked some outspoken local atheists, who also go by nuanced names such as freethinkers, anti-theists and secular humanists, about their worldview and how it meshes with American society.

Ingrid Saber is a petite, bespectacled woman who thinks religion has too much power over all the political parties, with the possible exception of the Communists. She's a friend of Swango's who considers herself anti-theist, is clearly pained by firm handshakes and refuses to part with much personal information, including her age, for fear that someone might steal her identity.

"I don't like to discuss my private life," Saber said, when asked about her line of work at a meeting of the Southern Arizona chapter of the Center for Inquiry, a community for the godless.

The Weekly phoned Saber about a day after she whispered her phone number at the meeting. She said people she had met in local atheist groups were "pretty gentle and fearful"--gentle, because they're inoffensive creatures; fearful, because of what happened to Swango.

"I think they're surprised, those who know what I'm going to do, that I'm doing it," Saber said. "But Robert needs some help." She was referring to her plan to hold a "If You Feel Creepy, Shed Godizm" sign in the same spot where Swango held his months earlier, in a show of support.

Saber, like Dawkins, doesn't agree with the religious foisting themselves upon others.

"These people are oppressive and forceful, and they will not allow you to be free of their superstitions," she said. "Religious people did not invent the concept of treating other people decently. This was already realized by human beings long before any preacher ever showed up."

She put some of these frustrations to paper when she wrote a poem called "Preaching Leeches" and distributed it to friends and acquaintances before Swango's trial:

These leeches are trained to distort your good mind

With god myths and guilt trips and traps of that kind.

From pulpits they worm their way into your head

Depositing eggs of self-doubt and self-dread.

They work on your children, the little girls most

By age 6 or 7 we'll have them, they boast.

And tell you on TV, distrust your own sense

While crowned and shielded at your great expense.

So guard what they covet. Protect yourself well

They're in a position to make your life hell.

Another point of contention for Saber is the notion that women have a subordinate role in the Judeo-Christian and Islamic traditions. Still, according to a 2001 report from The Pew Research Center, nearly half of the women in a mixed-sex group of more than 2,000 said they went to church once a week, compared to one-third of the men. Saber attributed the higher numbers to gullibility.

"They're naïve; they feel helpless, and they fall in love with their captor," she said. "It's a strange thing, but that's what happens."

All this might seem like so much religious-people bashing, yet Saber said she's friends with people who are into God, because they respect her views.

But mix politics and religion? No thanks.

"When they (religious people) start interfering with our form of government, when they are telling the schools that the children have to say a pledge that says 'under God,' they have crossed a very, very important line," Saber said. "This is a lesson to children that this is a nation under some God, and that's the way it is. ... They're being inculcated and made superstitious by their school teachers."

There are many misconceptions about atheists, according to Rich Richey: "They are immoral, lawless. Since they don't have a religion, they obviously must not have a morality," Richey said, repeating some of these misconceptions. "Morality and atheism are actually quite compatible."

Richey, 69, sees morality as a rational extension of the Golden Rule: Do unto others what you would have others do unto you. "That's what society is all about," he said. "If I do more good things for other people, then it's somewhat more likely that they'll do more good things for me. And our society flourishes."

Richey is a retired lieutenant colonel in the United States Marine Corps, and said he first started questioning his Christian faith when he began his education. He was also an acolyte who at one point considered becoming a priest. Now, he's fine with the word atheist--even with all the negative connotations it's amassed over the years.

"I don't find the need to announce it at all," he said. "It's simply that this is my conviction, and if somebody makes an outrageous statement, as often happens in support of religious perspectives, then I think I have a right to assail that on a strictly intellectual basis. I don't think religion deserves the respect it demands. In other words, it should not be insulated from logical inquiry."

Richey is a Republican. He said people tend to equate the GOP with the Christian right, even though there are many people in the party who don't have a religious perspective. On the other hand, it could be said that people tend to associate secularism--and by extension, atheists--with the Democrats.

Regardless, he described President Bush as "an honest man, a man of courage and, frankly, of vision." In other words, as an idealist in the style of President Woodrow Wilson.

"If we can keep the nation together long enough to achieve the victory we need to in Iraq, I suspect someday, somebody will see if there's space on (Mount) Rushmore," he said. "Because what he's doing is creating a revolution in the heart of Islam. We must win it there, because if we do not, Islam will continue its march throughout the world. It is a very, very dangerous entity in today's world."

He doesn't agree with it, but Bush's penchant for mixing religion and politics is his own choice, Richey said.

"If he wants to be that way, that's OK," he said. "If he starts putting into place religious things that require some kind of religious effort on my part, then that's bad." He cited the addition of God into the Pledge of Allegiance as a nettlesome example.

"Believe whatever you want, but do not enforce your beliefs on me or require conduct from me because of your religion," he said. "That's all I ask of a religious person."

Speaking of religious people, Dr. Stephen Uhl used to be one. While Richey only considered the priesthood, Uhl went ahead and took the plunge in the Catholic Church. And that gives him a unique point of view for discussing the virtues of atheism in his book, Imagine No Superstition: The Power to Enjoy Life With No Guilt, No Shame, No Blame.

"It was a gradual thing," he said, "after a special insight in a meditation one morning in the Benedictine monastic chapel in Aurora, Ill. In the meditation, I was discussing with myself the proofs of God's existence, and I came to the insight that the strongest one that St. Thomas Aquinas offers doesn't really hold up strictly, even though it had been taught as such by the Catholic Church for centuries. I guess that was the start of my agnosticism."

Uhl is referring to Aquinas' causality proof or cosmological argument for the existence of God, which, briefly put, states that God is the original cause for all the effects that have followed in our universe.

A "conditional prayer" for the Almighty's mercy when the brakes in a car he was driving locked up took him even further away from Catholicism. He had serious doubts about God's existence.

With time, "I simply began to work, in order to avoid all hypocrisy that I could, for the exits, to develop a responsible divorce from the monastery and the Church," he said. "Within the next year and a half or so--less than that, actually--I left and became a teacher in the public schools for a while."

He eventually married and got a doctorate in psychology. Uhl wrote about how proud his mother was when he entered the priesthood, and he told the Weekly over the phone how broken she was when he left it.

"One of the family myths is--and it's probably true--that one of the very happiest days of her life was when I got ordained, and the saddest was when she learned that I was leaving the priesthood and the Church," Uhl said. "But it didn't destroy our love at all."

Annie and Brandon Kelly, both 26, are a married couple who grew up in evangelical families. They both now call themselves atheists. Their parents have not officially been told.

The Weekly met with the Kellys outside a shuttered café near the University of Arizona, where they're both graduate students. Brandon, who was wearing a striped polo shirt, had a solemn demeanor. Tattoos festooned Annie's arm; she also sported black fingernails, a nose piercing and dangly earrings.

They got married about five years ago in a "Christian, very religious wedding," Annie said. Three years ago, after moving to Tucson from Michigan, they started questioning. They put a name to their new worldview last year.

"Getting past that initial step of actually being honest with yourself and saying, 'OK, I really don't believe in my religion anymore; I really don't consider myself a Christian anymore,' is probably the hardest step to get over," Brandon said. "For a long time, I sort of--on an intellectual level--didn't really believe it anymore. At the same time, when you grew up with it, and you're told, 'Be a Christian; it's part of your identity, and everyone else is Christian, too,' it's very hard not to believe it anymore."

"It's scary to start questioning it, and be like, 'I don't know if I believe this anymore,'" Annie said. "And you start feeling guilty that you're not as strong a believer as some other people.

"I kind of had the assumption that if you're not a Christian," Annie said, "there's no reason to want to be a good person. But when I finally came to the realization that I can still be a good person, I can want to live a good life, there doesn't have to be a reason for me to be a good person--if that makes sense--then I became more comfortable."

With a state of mind that sounds similar to the one experienced by homosexuals when they come out of the closet, Annie and Brandon haven't had the "very special talk" about atheism with their parents; the couple thinks they'll be be disappointed when they get the official word. Mom and dad undoubtedly know on some level, but the negative (atheism) is downplayed while the positive (the potential for their return to the fold) is accentuated, Annie said.

"My parents will be like, 'Where did I go wrong?'" she continued. "My mom will probably say that she didn't do this enough for me, maybe she wasn't in contact enough for me, maybe she didn't send me enough books--which she did. I still have all the books sitting on my bookshelf. It'll be a big disappointment."

Brandon added: "I think also that both of our parents will blame the spouse to a certain extent. But it's not easy to bring it up. It just hasn't really come up, and it's been such a gradual process for us. It wasn't like we woke up one day and were like, 'Oh, we're atheists.' They don't really make a card for it."

UA Professor Guy McPherson would like it very much if you thought about the impending apocalypse as you go about your holiday season. It will reach critical mass in about a decade, as world oil production dwindles and prices skyrocket. McPherson, a self-styled "social critic" who teaches classes about sustainability and conservation biology--and who wrote a guest commentary published by the Weekly last April expressing some of these views--can draw you a bell-shaped curve at the drop of a hat depicting the decline of oil production.

He loves doing it--seriously.

"In 2015, the price of oil is projected to be $380 a barrel," McPherson said. "And when oil costs $380 a barrel, the U.S. dollar will be worth exactly zero. Nothing. Think 1,000 percent inflation, associated with the economic collapse of the former Soviet Union, Argentina, Mexico, the Far East and so on. Looks like it's our turn."

Screw getting a more fuel-efficient car.

"That's the least of your problems," said McPherson, a tall, lanky man who flashes mischievous grins. "This country mainlines oil, more than any other society in the history of humanity." The gross domestic product is correlated to the amount of driving Americans do on their cars; drivers collectively log about 20 million miles in the Tucson metro area each day alone, he said. Imagine the paralysis when Americans can't get their fix.

What does this have to do with atheism? Americans will need to learn to "suspend their belief"--not disbelief--"so they can participate in the real world" and confront things like critical oil shortages, McPherson said. He claimed to be an agnostic professionally, because science has no way of testing whether God is real or not. Personally, he said he's a non-theist.

If there is a link between falsehoods being passed from parent to child, as Dawkins suggested in Wired, then McPherson isn't sure how to break it.

"I don't know what to do with the parents. I don't know what to do with the indoctrination that those kids are getting," he said, adding that they're not being taught the facts as we know them. "I think it's obscene the way that American children are lied to from the day they're born. It's absurd, and it's obscene."

As evidence, McPherson cited an essay written by Tucson atheist Gil Shapiro in which Shapiro described listening to a child's conversation with a religious leader on a radio program.

"This 11-year-old kid calls into this radio show and talks to this religious leader in Tucson," he said, "and this religious leader tells him that the Earth is between 6,000 and 10,000 years old--and he tells it as a fact. He's lying to an 11-year-old. There has to be consequences for that."